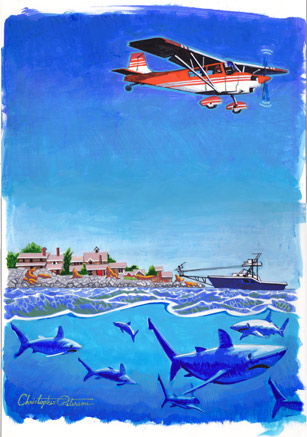

From 1,200 feet off Chatham, Massachusetts, the Atlantic Ocean gleams like a mirror. Its bleached-white beaches stretch out along the outer Cape in a line that extends to infinity. Submerged sand bars off Monomoy Point appear iridescent in the blue-green water. But pilot Wayne Davis notices none of it. As he rocks his Citabria from one side to the other, chin tucked into his chest, his eyes are fixed straight below. He is looking through the water, searching for shadows.

An aerial fish spotter, Davis, 66, has made a career flying low over the waters off New England. He’s logged more than 15,000 hours helping to guide fishing boats to swordfish and schools of giant tuna. On this mission he is flying for science, helping researchers locate great white sharks for the Massachusetts Shark Research Program. The fearsome creatures, once rarely seen in these waters, have become frequent and disquieting visitors, attracted by the growing population of gray seals off Chatham and on nearby Monomoy Point.

Dr. Greg Skomal, 52, is a marine biologist with the Massachusetts Department of Marine Fisheries and project manager for the shark research. While white sharks off California, Australia, and South Africa have been extensively studied, scientists haven’t had many opportunities to study Atlantic whites. Only 503 sightings of white sharks were reported along the entire Atlantic Coast before 2004.

Since 2009, however, 30 sharks have been tagged, some with satellite transmitters that allow the public to follow their movements online (www.ocearch.org). By identifying and tagging these mysterious and misunderstood creatures, scientists can learn more about the sharks’ biology and behavior—their migration patterns and range, where they breed and mate, their approximate numbers, and whether their population is increasing or declining.

What lies beneath

Davis flies along the beach, peering into the shallow waters and shoals offshore. Sharks typically are found near the shore, often just outside the surf line. Davis likes to fly at around 1,000 feet, low enough to make out shapes in the water yet high enough that glare is less of a problem. Forty years of fish spotting has conditioned him to recognize the telltale signs of what lies beneath.

What looks like a ruffle of wind on the surface Davis can tell is a school of herring; what seems a cloud of mud along the bottom are “pogies,” or menhaden; a distant splash could be a swordfish breaching. Seals, however, are easy to spot. They cavort in the surf, their distinctive cigar-shaped bodies skimming just beneath the surface.

“There!” shouts Davis, dipping a wing.

Below there seems to be just water and sand. Davis is circling over a spot less than 100 yards off the beach, where the tidal flat drops off and whatever isn’t on the surface quickly becomes lost in the shadow of deeper water. Along that edge, there is a shape—vague and indistinct—moving slowly along the edge of the drop-off, but it disappears as the airplane moves and the sun glares brightly off the water. Davis continues to circle. It comes back into view, this time more clearly. Compared to the seals, this shape is more teardrop, its motion from side to side—like a fish, not a mammal.

“Hey, Cap,” Davis radios down to Bill Chaprales, captain of the Ezyduzit, a 32-foot harpooning boat hired for the project. “I got one.”

“Yeah, Wayne, where are ya?” Chaprales answers.

Pilot and boat captain work as a team. Davis gives his location along with the approximate size of the shark (12 to 15 feet long). As Chaprales motors toward the area, Davis circles over the animal, following as it lazily makes its way along the beach. He directs the boat precisely to the prey, maneuvering it into position, mindful to keep the boat behind the shark so as not to spook it. “It’s about 1:30, call it 12 boat lengths,” Davis says.

Davis and Chaprales have known each other for years, and worked together with Skomal in 2007 on a similar project tagging basking sharks. Chaprales has been at it even longer; he began tagging giant bluefin tuna for the National Marine Fisheries Service in 1976. He has invented and patented a tagging pole specifically designed to minimally harm the animal being tagged.

A good fish spotter is crucial to tagging sharks, Skomal says. Aerial drones or fish-finding sonars just wouldn’t work in these conditions.

The shark starts to drift off into deeper water, where it might be lost. Davis radios Chaprales, directing the boat so that it herds the shark back toward shore, where it can be more easily pursued.

“Okay, he’s at 11:30 now and about four boat lengths,” Davis radios. “Moving just parallel to the beach.” Chaprales’s son, Nick, guns the boat to close the gap. Meanwhile, Chaprales makes his way out onto the pulpit, a 20-foot rail extending from the bow of the boat, tipped with a small stand enclosed by a waist-high circular railing.

“Yeah, Wayne, where are ya?” Chaprales answers.

Pilot and boat captain work as a team. Davis gives his location along with the approximate size of the shark (12 to 15 feet long). As Chaprales motors toward the area, Davis circles over the animal, following as it lazily makes its way along the beach. He directs the boat precisely to the prey, maneuvering it into position, mindful to keep the boat behind the shark so as not to spook it. “It’s about 1:30, call it 12 boat lengths,” Davis says.

Davis and Chaprales have known each other for years, and worked together with Skomal in 2007 on a similar project tagging basking sharks. Chaprales has been at it even longer; he began tagging giant bluefin tuna for the National Marine Fisheries Service in 1976. He has invented and patented a tagging pole specifically designed to minimally harm the animal being tagged.

A good fish spotter is crucial to tagging sharks, Skomal says. Aerial drones or fish-finding sonars just wouldn’t work in these conditions.

The shark starts to drift off into deeper water, where it might be lost. Davis radios Chaprales, directing the boat so that it herds the shark back toward shore, where it can be more easily pursued.

“Okay, he’s at 11:30 now and about four boat lengths,” Davis radios. “Moving just parallel to the beach.” Chaprales’s son, Nick, guns the boat to close the gap. Meanwhile, Chaprales makes his way out onto the pulpit, a 20-foot rail extending from the bow of the boat, tipped with a small stand enclosed by a waist-high circular railing.

Will fly to fish

Some pilots fly for a living. Other pilots live to fly. Davis flies to fish. Growing up in Point Judith, Rhode Island, fishing was pretty much all Davis knew or wanted to do. Fit and wiry, he speaks in exited bursts of conversation. “I remember my first trip swordfishing when I was nine years old.”

After getting out of the U.S. Army on May 9, 1969, he returned home and to swordfishing. In 1973, he started flying with the sole intention of being an aerial fish spotter. Coincidentally, his single-engine, 150-horsepower, tandem two-seat Citabria came out of the factory the same day he was discharged from the Army. In addition to its standard 39-gallon fuel capacity, the Citabria’s outfitted with a 60-gallon belly tank, giving Davis enough fuel to stay airborne for more than 13 hours. And there were days—many days, Davis says—when he needed every drop of gas he could carry. His legs cramped from the constant application of rudder, so he rigged a bungee cord that he looped around one of the rudder pedals to give his feet a break.

Davis flies out of Plymouth, Mass-achusetts, about an hour and a half drive from his home, so during fishing season he pretty much lives at the airport. The hangar he shares with another pilot looks like an aviator’s flea market. A Cessna 150’s fuselage is wedged up against one wall. What looks like the fuselage of a Luscombe or a Stinson lines another. To the side is the bare metal frame of another aircraft. There’s a haphazard collection of doors, cowling covers, various airfoils, and all kinds of parts. There is, in fact, barely room for one airworthy aircraft among them.

The mid-1980s and early 1990s were great times to be an aerial fish spotter, Davis says. Swordfish and schools of giant tuna ran thick and close to shore, and if you were willing to put in long hours, you could make a good living. At one time there were as many as 30 aircraft working New England fishing grounds, and Davis recalls days in which 10 airplanes might be crowded over a small area in a scene right out of the movie The Blue Max. Airplanes circling, their pilots all looking down at the water; boat captains all looking at the sky, calling out traffic to pilots. It was controlled mayhem.

Airplanes and boats communicated using encrypted radio, to avoid sharing the locations of fish with rivals. A pilot might see a school of fish, communicate its position to his boat, then fly off in another direction to draw the other boats away. It was a tough business, says Davis, and dangerous. Two pilots were killed in a collision off Gloucester in 1958. Another pilot was rescued after his airplane crashed off Cape Ann in 2012. Davis recalls looking up one time to see the nose of another airplane filling his windscreen. Only by sheer luck did the two not collide. “I am thoroughly amazed we didn’t crash,” Davis says.

Afterwards, Davis called the other pilot, whom he knew well. “Whew, John, that was real close,” Davis told him.

“What d’ya mean?” the pilot answered. He was too busy looking at the water and never saw a thing.

Around 1980 Davis started taking photos during his flights. “Nothing serious,” he says, just a hobby to help him pass the long hours, a way to capture a big swordfish or a whale or some of the sights he came upon. It got to be a habit.

By the late 1990s the big fish—swordfish and giant tuna—started getting harder to find, their populations thinning or moving further offshore toward the continental shelf, or north into the Gulf of Maine or Canadian waters. Fewer harpooners, combined with increased fishing regulations and the rising cost of avgas, meant fewer aerial fish spotters. Today Davis can name just four spotters flying off the Cape.

Davis started working with divers, underwater cinematographers, and researchers such as Skomal, all of whom use his skills at finding and spotting various wildlife. He also got serious about his photography. He began flying on his own very far offshore, to the open ocean beyond the fishing grounds, in order to photograph wildlife—manta rays, blue whales, giant pods of porpoises, schools of hammerhead sharks. He started his own photography business (www.oceanaerials.com).

Seal explosion

The appearance of sharks coincided with the explosion of the Cape’s seal population. Hunted almost to extinction for pelts and meat, seals were a rare sight in New England 40 years ago. In 1972 they gained federal protection, and over the past 20 years the population off Chatham has thrived. A survey in 1994 counted 2,035 seals. A similar survey in 2011 counted 15,700.

Not all residents welcome the seals’ resurgence. Some local fishermen see the seals as competition. “I guarantee those seals have caught a hell of a lot more cod than the port of Chatham has,” complained a local fisherman to The New York Times last summer.

In 2004, a 13-foot, 1,700 pound white shark created a sensation after getting trapped in a salt pond near Woods Hole on Cape Cod. Five years later, in 2009, Chatham beaches were closed after five sharks were spotted off Monomoy Point. The booming seal population has drawn the white sharks, Skomal says. Seals bearing injuries from shark attack—and seal carcasses—have become more common.

For humans, the chance of being attacked by a shark is extraordinarily low. More people are killed by collapsing sinkholes than white sharks each year in the United States. “But of course, perception becomes reality,” Skomal says. In 2012 a swimmer survived an attack by a white shark off Truro on Cape Cod, the first such attack in New England since 1936. Information collected by the shark project is shared with towns and communities so they can make decisions about beach closings and public alerts.

Harpoon practice

After first identifying the sex of the shark using an underwater camera attached to a long pole, the shark is tagged using a harpoon. Both harpooning and tagging require a combination of timing, practice, and athleticism. “A lot of people think they’re good at harpooning,” Davis says. “But few actually are.” Chaprales is one of the best. He’s tagged hundreds of tuna, basking sharks, and great whites—and brags that he has never missed his target.

Typically the harpoon is a seven- to 12-foot steel or aluminum rod tipped with a brass dart. For tagging, the lethal dart is replaced with a barbed device that attaches a transmitter. The device records the shark’s migration routes and patterns, water temperature, how deep it dives, and for how long. At a predetermined time—usually January or February—the device pops off the shark, floats to the surface, and transmits the data to researchers via satellite.

“Wow, that’s a big fish,” Chaprales shouts to the crew as the creature slides underneath the bow of the boat. He braces himself against the crow’s nest, poised to throw the harpoon when the animal reemerges. He throws, hitting the shark on his first throw. The shark itself hardly seems to notice, and continues on its way. Davis circles overhead, continuing to follow the animal so the crew can then get a tissue sample for DNA testing using a differently tipped harpoon.

“A bit to port,” advises Davis. “Four boats; three boats; dead ahead, two boats.”

Chaprales gets a bead on the shark. He throws, again hitting his mark. This time the shark thrashes angrily, throwing up a huge spray of water and foam that rocks the boat.

Davis continues patrolling the beach. Over the next couple of hours he spots two more sharks. Both manage to slip away before Chaprales can tag them.

After seven and a half hours in the air, it’s time to go home. For Davis, it’s been a relatively short day, but successful. Four sharks spotted and two tagged. On the return flight over Cape Cod Bay, he continues to visually scour the water, looking for something, anything. It is a compulsion, he admits, a passion. Not long ago he took a vacation to Hawaii and, even from 35,000 feet, he found himself looking at the water for shapes, shadows, signs of life. “I didn’t sleep a wink,” he says. “You just never know what you’re going to see. It’s never the same, never boring.”

Tom LeCompte is a freelance writer and part-time Boston cab driver.