Turbine Pilot: Proficiency

Training once a year isn’t the best way to stay sharp

As a pilot examiner conducting in-aircraft recurrent training, I see all too often the truth of the adage that a pilot is never as proficient as the day of his checkride. After weeks of initial ground and flight or simulator training—eating, breathing, and sleeping the intricacies of the aircraft being studied—a pilot can immediately recall the smallest details of the jet. Checkride complete, he may have the best intentions to stay on top of system knowledge, yet day-to-day, “all systems normal” flying replaces rigorous study and emergency procedure drills. Quickly all the subtle systems gotchas and procedures for abnormal operations are dumped from short-term memory.

While some of the forgotten information is trivial, systems minutia, a large amount is directly related to safe operation of the airplane. In particular, the profiles to safely fly the less-common maneuvers such as go-arounds and single-engine approaches often are lost quickly. Given that even when flown by a proficient pilot these are the most challenging maneuvers to execute, losing proficiency could prove disastrous.

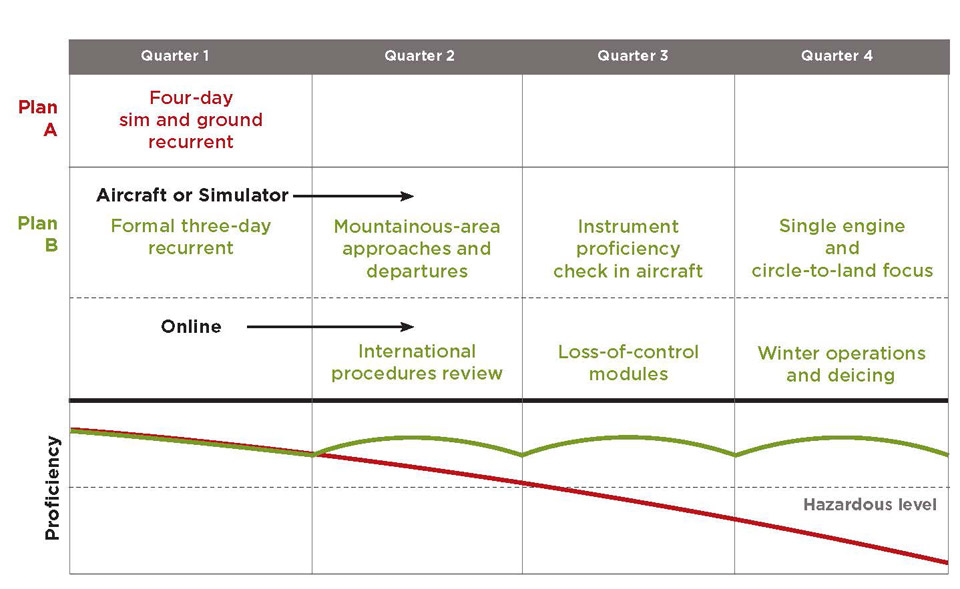

Pilots can avoid the dramatic swings in sharpness by treating recurrent training as a continual process rather than a periodic event. If training is conducted in smaller chunks, but with higher frequency, less time passes to allow “brain dump” or the formation of bad habits. Additionally, many simulator instructors say that clients who only come in once per year need the full program time allotted just to regain a feel for the sim, polish rust off the required maneuvers, and complete the mandatory FAR 61.58 check. By training in an out-of-the-box manner, more varied scenarios can be worked in, creating a richer overall experience.

Many of the large simulator schools offer a contract that allows for unlimited training time during the year, either part of a formal recurrent course or simply in small, ad-hoc chunks. Considering the high cost of simulator time, these packages represent an amazing value. For those unable to get to a simulator every two or three months, in-aircraft training with an experienced instructor can accomplish much of the same work. How does two hours of challenging mountain airport operations sound? Or two hours focusing on tricky departure procedures flown with an engine failed? A good instructor, armed with some information about a pilot’s operating profile, can create fun and challenging sessions in an airplane or simulator.

For the academic component, combine web-based enrichment courses with self-study of aircraft profiles, limitations, and memory items, rotating through all the core information every six months. Create a calendar of the online training you will accomplish in the next year, be it free (AOPA’s own Air Safety Institute is a great place to start) or paid (Flight Safety International and NBAA have good catalogs). If putting together a plan sounds daunting, have an experienced instructor help; he or she will be able to suggest the most common areas in which pilots develop rust and a schedule to keep proficiency high year-round.

Neil Singer is a Master CFI with more than 7,200 hours in 15 years of flying.