Climbing out of Duxford, England, through 1,500 feet, I saw the bogey half a mile out, coming fast. As I watched, he rolled knife-edge and pulled hard towards us. From behind me Al Pinner called “My airplane,” and I gladly relinquished the stick. I was way out of my depth here. The throttle came forward and our Spitfire’s nose swung skyward in an arc so graceful that I hardly noticed the G-forces crushing the breath from my body. Our right wing was down, its iconic camouflage and roundel-adorned ellipse sucking every last bit of traction out of the air.

The Merlin’s 12 cylinders had clawed halfway through some sort of chandelle on steroids when Al reversed sharply, now left wing down, and we pirouetted through the air over the beautiful English countryside. Seconds later, that same countryside filled the windscreen—but now with the challenger’s silhouette pinned in our sights like a bug on a collector’s table. Al keyed the mic to cheerfully announce “Guns,” then broke off the mock attack and swung us outbound again. He re-trimmed the airplane, then gave a quick shake on the stick to indicate that I was in control again: “OK, Pablo, your airplane. Have fun.” Have fun? My brain was still trying to catch up with the chain of events that started when I first pushed the throttle forward, five miles earlier. How could I not have fun? I was flying a Spitfire!

The Boultbee Flight Academy

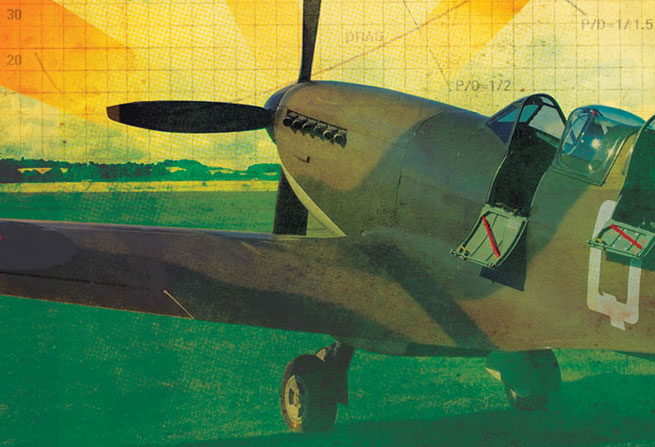

The Boultbee Flight Academy offers an introductory course that takes pilots through two and a half hours of flight time: an initial hour in a de Havilland Chipmunk, then 45 minutes each in a Harvard (what we here in the States call a T–6 Texan), and the school’s centerpiece—G-ILDA, a two-seat Spitfire TR.9. There is also a 10-hour Spitfire transition course for those who have the desire—and means—to solo.

So, how much does it cost? A lot. Flight time in the United Kingdom is measured from wheels up to wheels down, and an hour of it in G-ILDA will set you back roughly $5,500. That’s more per hour than a P–51, a MIG–21, and almost anything else you can pay money to spend time with. It’s more than I paid for my last car. But flying a Spitfire was a dream that I’d had since I was a small boy “flying” a cardboard box in my parents’ living room. So when some friends tipped me off about Boultbee, I knew it would be only a matter of time before I cashed in all the spousal favors I’d earned in 18 years of marriage, and signed up to spend a few hours living my dream.

Spitfire training

My first full day at Boultbee was spent learning the Spitfire’s systems with crew chief Mark “Bing” Crosby. I learned that, in many ways, the airplane resembles a human body. On the surface, it’s a thing of beauty, but if you peek inside, you’ll find such a bewildering tangle of tubes and unrecognizable doodads that you marvel the thing can work at all. The maze of steel and copper tubing feeding pneumatic and hydraulic pressure to flaps, radiator flaps, propeller, and landing gear is a Gordian knot. To fully understand how they all work together, as Bing said, you need to either be very clever or completely mad.

My flying instructor, Al Pinner, was a former Royal Air Force Harrier and F/A–18 Hornet pilot. His precision, clarity, and “no problem” demeanor give the impression that anything short of shedding pieces of the airframe is just another learning opportunity.

The first real challenge of actually flying a Spitfire is getting it to the runway. It was never intended to be taxied on pavement, and a few minutes on the apron with its single-lever pneumatic brakes and castering tailwheel will humble even the most seasoned pilots.

Once on the runway, it’s customary—because of the long nose—to line up at a 30-degree offset, to get a clear view of where you’re heading once you add power. You crank the throttle friction lock as tight as it will go—the need for this will become evident in a moment—and smoothly push the throttle forward to six inches of boost.

Unlike other high-performance piston aircraft, in which a manifold pressure gauge indicates the absolute air pressure inside the engine intake, the Spitfire’s gauge measures the difference between ambient and internal pressures. The standard six inches of boost (about 36 inches of manifold pressure) yanks the lightly loaded Spitfire forward with alarming acceleration across the grass. The boost gauge reads all the way up to 24 inches for wartime operation with high-octane gas. Bouncing and careening down Duxford’s grass runway, I’m dancing like mad on the rudder pedals to keep everything pointed in the right direction.

The airspeed indicator betrays the Spitfire’s range: 90 mph—rotation speed—is just a smidge off the six-o’clock resting position of the needle, and the indicator markings go around the inner face one and a half times, up to 480 mph. Almost as soon as the needle comes alive, I’m at 75 mph, the speed at which Al directed me to raise the tail—“But not that much!” he corrects. You want it just high enough that the airplane won’t lift off before you’re ready. By the time I’ve got the tail where I want it, the ASI is passing 95, and the wheels give me one last good bounce.

There’s no time to sit back and savor the experience. With a positive rate of climb, it’s time for the landing-gear dance: Apply the brakes with the right hand on the spade-mounted lever. Then switch hands; left hand from throttle to stick and right hand to the gear lever. If I failed to sufficiently tighten the throttle friction lock, now’s the time it will slip back to idle—not what I want with that lovely English countryside so close below.

My right hand pushes the gear lever through the much-rehearsed sequence: push down (two, three); smoothly forward; push up (two, three, four), and wait for the pop-back to tell me that the gear is locked up and pressurized. Then switch hands back to the throttle quadrant. Reduce boost to four inches, bring rpm down to 2,400, and trim for climb at 140 mph.

I take a quick breath and bank into the crosswind turn. The sweep of the countryside takes me by surprise as the wing comes down and the graceful nose arcs around. That’s the moment time stands still. I’m flying a Spitfire. All at once, the Byzantine systems and plumbing under the hood are forgotten; the numbers, sequences, and procedures fall away. What remains is the singular experience of my hands on the stick and throttle of a craft that will leap to do my bidding almost before the thought has fully formed in my head.

The intercom is almost useless with the Merlin producing so much power. I retard the throttle to zero boost and tell Al, in the back seat, that I’m going to make a few S-turns to get a feel for the airplane. That’s when the tower calls incoming traffic and the dogfight begins.

Flight characteristics

Once I’d recovered from the first bout of unexpected excitement of the flight, I began feeling out the flight characteristics that made the Spitfire famous. The airplane is neutrally stable around all axes, so a constant hand on the stick is needed. A light hand, too, as stick forces are minimal in both pitch and roll. At higher speeds, the ailerons stiffen, but the elevator remains, as the Pilot Notes phrase it, “particularly light.”

Climbing northward, I explore the Spitfire’s envelope. S-turns and Dutch rolls felt conventional so, with a word of warning to Al, I rolled left into a steep turn. Nose on the horizon, a little back pressure to bring her around, and suddenly my arms and brain felt like lead. The back pressure I associated with a two-G steep turn was generating more than four Gs in the Spitfire. I was going to need a much lighter touch on the stick to fly well.

In spite of its dogfighting history, the Spitfire does not like negative—or even zero—Gs. For wingovers, set the throttle to four inches of boost, prop to 2,400 rpm, and lower the nose slightly to get 240 mph. Then pull gently until you’re “feet to the sky,” and roll over 135 degrees. Increase back pressure to maintain one G as the airspeed drops off, then go over the top, still pulling as the nose comes down. Roll back upright, and done. Except that now you’re aimed for the dirt, staring straight into the lovely English countryside as the airspeed indicator winds up like a crazy clock.

The instinct, of course is to pull back hard, but that will get an overstressed airframe. As the airspeed builds up—and there’s plenty of room for it to build before getting to the 400-mph never-exceed limit—the elevator forces do get lighter. And with the aft center of gravity produced by having both student and instructor aboard, the Spitfire likes to tuck up; push forward to keep from exceeding the recommended four-G recovery limit as you bring the nose back up to level flight.

Al had me do a couple more wingovers until I got the hang of it, and then talked me through loops and victory rolls. Can’t be a proper Spitfire pilot without a good victory roll, can you?

Slow flight and stalls were, surprisingly, nonevents. We’ve all read about that famous elliptical wing, how it wrings everything it can out of the air before suddenly and completely giving up. So I was prepared for a somewhat dramatic transition as we crossed the line between “flying” and “plummeting.” With power reduced and the nose raised for slow flight, G-ILDA was happy to make gentle turns while the airspeed indicator bobbled down near the bottom of its range. Controls forces softened, but the airplane felt buoyant, reminiscent of something with much lower wing loading. Then, somewhere below what felt like reasonable flying speed, the wings bobbled momentarily. The nose dropped a little more suddenly than I’d expected, but a nudge—just a nudge—of power got us flying again.

Between the high-strung Merlin engine and the airplane’s propensity for getting shot at, dead-stick landings were high on the list of Spitfire pilot survival skills. Best glide is 100 mph, and even as aerodynamically clean as she is, the airplane comes down pretty quickly. From 3,000 feet, I’ve got time for one 360-degree turn over the designated field before I’m set up on high key for the downwind. A gentle curving base leg, keeping gear and flaps up, puts me on high final, lined up with perhaps a five-degree slope to the intended touchdown point. Al let us come down to about 200 feet over the field before instructing me to add climb power, and we clattered away over farmhouse roofs in a stampede of cylinders.

Landing

They say that the Spitfire is an easy airplane to fly; it’s landing that brings pilots to grief.

They say that the Spitfire is an easy airplane to fly; it’s landing that brings pilots to grief.

In a normal approach you throttle back to 140 mph on the downwind, typically zero inches of boost or less; set trim; open the radiator flaps; and select the air intake to filtered. About 10 seconds before you’re abeam the touchdown point, you switch hands, do the gear dance in reverse, and verify it’s down and locked.

If this has gone smoothly, you’re now abeam, and it’s time to start down. Bring power back for the descent and slow to 110 mph, beginning a smooth, continuous turn back to the runway. Al advises trying to keep my wing tip on the touchdown zone for the first half of the turn, throwing in those 85 degrees of (clunk! clunk!) flaps and trimming as I go. The nominal start of the base leg is when one pushes the prop to fine pitch and slows to 90 mph. But rather than a square turn to final, Spitfire pilots prefer to come at the runway from a 20- to 30-degree angle, crossing the fence at 85 mph before aligning for the landing.

In all my landings over four days, I rarely managed that perfect approach, and found myself making S-turns and peering down either side of the nose, grateful that we had a control tower to assure me that no stray livestock was obstructing my path forward.

Then, the landing itself—you really want to be at precisely 85 mph coming over the fence. None of that, as Al would say, carrying an extra five for Mum. If you do, you’ll be carrying it all the way down the runway to the farmer’s field. I consistently found myself high and hot, carrying not only an extra five for Mum, but another few for her sister, the kids, and the cousins. Most times, I was able to compensate, juggling pitch, power, pitch, power—but never properly catching up before the ground loomed and I had to transition to the roundout.

Al staved off the worst consequences of my misjudged approaches and badly timed flares by nudging the stick and cushioning the blow with a judicious jab of power, but it took well more than a dozen landings before I managed to get the sight picture right.

Finally, on the last flight of the last day, it all came together. Hands and eyes dancing across the cockpit, lighting on the right thing at the right moment. Swooping down on the 20-degree angle from centerline, airspeed glued on 85 mph. Over the threshold at 30 feet, into the roundout, held precisely at three-point attitude as speed bled off, and the wings negotiated with the diminishing cushion of air keeping them from the ground. Then not so much of a thump as the sound of wheels catching fresh-cut grass and settling in. Feet not only responding, but anticipating any notion the tail might have to swing wide. Slower and slower, with the stick back—and then taxiing, making a slow turn in across the grass, keeping it rolling as I let myself savor the exquisite, improbable sensation. This is what it feels like to fly a Spitfire.

David “pablo” Cohn is an antique aircraft owner and flight instructor in the San Francisco Bay area.