Instrument Insights: Special PIC certifications

Not for the faint of hear

Anyone with an instrument rating—especially pilots who first spent hours sneaking around beneath low clouds or in poor visibilities—appreciates their new ability to fly anywhere in any kind weather. Well, almost any weather. In the United States and in some countries around the globe, flying into some airports in poor weather—and sometimes even in good weather—is only allowed when the pilots have received specific training.

Anyone with an instrument rating—especially pilots who first spent hours sneaking around beneath low clouds or in poor visibilities—appreciates their new ability to fly anywhere in any kind weather. Well, almost any weather. In the United States and in some countries around the globe, flying into some airports in poor weather—and sometimes even in good weather—is only allowed when the pilots have received specific training.

Some restrictions are weather specific. A Category II authorization, for example, allows aircraft to shoot an ILS approach in weather below the standard 200-foot ceiling and half-mile visibility most of us are used to. A Cat II authorization requires regular simulator training to prepare the crew to flare when they might have glimpsed the runway environment only a second or two after breaking out of a 100-foot, or even lower, ceiling.

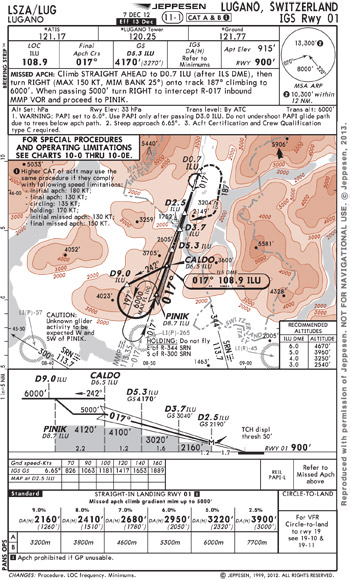

Sometimes the airport itself demands specific pilot training. The FAA’s Special PIC Qualifications list, Order 8900.206, highlights what airports require extra training before the first operation. In addition to a weather restriction, some airports demand training because extreme terrain may pose a risk to the flight. An approach into Aspen or Eagle, Colorado; Innsbruck, Austria; or Katmandu, Nepal, are places where pilots need to understand that straying from the final approach course, even a bit, might result in connecting with tons of nearby rocks.

Then there are technically specific airports. No one lands on London City Airport’s 4,948-foot runway without completing the familiarization training about the intricacies of flying an ILS with a much steeper than normal glideslope—5.5 degrees versus the standard 3 degrees. Pilots also must have completed at least three approaches at 5.5 degrees before a London City arrival, some of which can be accomplished in a simulator. While special PIC certifications are specific to the pilot, London City Airport allows only specific aircraft that are specially certified for the steep approach path, such as the Airbus A318, Dassault’s Falcon 900, Bombardier’s Dash 8, and the Learjet 45.

Of course, these are simply the restrictions and regulations that demand special qualifications and expensive recurrent training. But if one company’s Falcon 7X can make the approach to Aspen when almost no one else can, that might mean the boss can land some new piece of business while a competitor’s business airplanes are forced to either hold for the weather to improve or divert to Denver and endure a multi-hour automobile trip back to town.

In fact, economic incentives are really where special IFR procedures began years ago, when some commercial airlines saw an opportunity to serve a particular airport—and their competitors could not follow. Alaska Airlines famously pioneered the ability to successfully wind its way between a wide variety of enormous mountains in Alaska to deliver passengers safely. General aviation has simply piggybacked off many of these airline efforts.

Special training for pilots comes in two flavors, either airport familiarization or initial qualification training. Familiarization training—at airports such as Innsbruck, Austria, or the Portuguese island of Madeira—could be one pilot simply chatting in person or by phone with another about what they might face, or the training could be computer based to guarantee the crew understands the risks involved. Some airports are simply deemed too challenging to utilize without more in-depth simulator qualification training added to a few hours of formal ground school.

The payoff for all the work to earn and maintain a special pilot authorization can be spectacular. At Eagle Airport in Colorado, training for the Cottonwood Two departure procedure offers crews a completely different route through the mountains than the more commonly used Gypsum departure. Pilots of jets without the training must be able to meet single-engine climb requirements that will keep them clear of the rocks up to 12,000 feet if an engine should quit after takeoff. With the special qualification, that number drops to about 6,600 feet, which translates into the ability to carry more people or more fuel than an unqualified crew.

The traditional localizer DME approach into Aspen—field elevation 7,837 feet—carries minimums that will bring an aircraft down no lower than about 2,200 feet above the ground before a missed approach is required. Special PIC qualifications offer crews a full ILS approach that can bring them down almost as low as a traditional ILS.

In case you’re thinking you might just use the approach plate on your own, without the training, don’t bother searching for Aspen’s special ILS approach plate on your iPad, because it won’t be there. The actual approach plate is only handed over to pilots who have completed the qualification regiment with a training provider such as FlightSafety International. A bit of a disappointment does await the owner of a jet certified for single-pilot operation, such as a Phenom 100 or a Cessna Citation Mustang—special PIC qualifications are only handed out to aircraft operators who use them with two pilots on board.

The 8900.206 list of airports that require familiarization or qualification training is long and includes places with exotic names such as Akureyri, Iceland; Pago Pago, American Samoa; and Thule, Greenland. Search YouTube and you’re sure to uncover some of the videos shot by pilots on the way into and out of some of these airports, which make the dangers stand out pretty clearly. Or fire up Google Earth on your computer and take a look at the terrain you’d be flying around when you can’t see through the clouds, and you’ll see pretty quickly why these special PIC operations are not for the faint of heart.<

Robert Mark is a the author of the award-winning JetWhine blog.