The slash in the trees became visible from some 15 miles north as we descended out of 4,500 feet. A couple of miles beyond and easily spotted was Jockey’s Ridge State Park, the massive sand dune that is home to kite flying and hang gliding in the shadow of Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina—where, for pilots, it all began. As we approached, the slash widened and it became evident that buried somewhere in the trees was a runway. A few hundred yards south, high on a hill, stood the memorial to the Wright brothers—the same hill from which they launched their gliders from 1900 through 1902, each year bringing greater and greater refinement to three-axis flight control.

As I was established on a left downwind and feeling nearly ready to turn base, the trees finally revealed the approach end of Runway 2. With the gear and approach flaps already down, I cranked my old Bonanza around, added final flaps, did a final GUMPS check, and set up for a landing at the most historic site in aviation. For only the second time ever, the Bonanza touched down on the 3,000-foot strip of pavement first installed in the early 1960s. We back-taxied to the large parking area and stepped out to admire the view of the monument, anxious to visit the site where the brothers first launched on their powered flights.

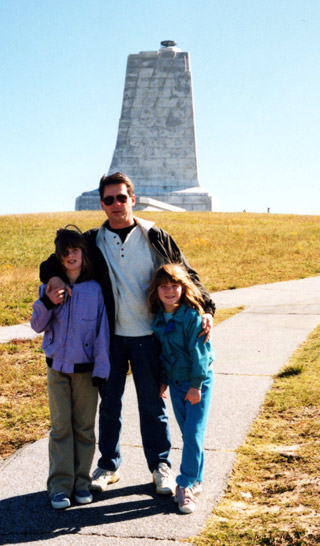

The landing at First Flight in May rekindled the same emotional response it did the previous time I had touched down there, nearly 13 years earlier and just a month after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. That trip was my first flying around the newly fortified Washington, D.C., airspace after general aviation returned to the skies during that tumultuous time. My wife was in the back keeping the girls entertained as we touched down for a visit to First Flight. I had them take a snapshot of me next to the airplane with the monument visible in the background—to this day the only photo of my airplane in my office, although a little faded now. And while my oldest daughter just graduated from college and the youngest finished her freshman year in college, it feels like the airplane, First Flight, and I haven’t changed at all. I still think I look like that young man in the photo, and the airplane still looks the same—on the outside. Inside, with a new interior and new glass cockpit since the last visit, the old girl looks a lot different.

The landing at First Flight in May rekindled the same emotional response it did the previous time I had touched down there, nearly 13 years earlier and just a month after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. That trip was my first flying around the newly fortified Washington, D.C., airspace after general aviation returned to the skies during that tumultuous time. My wife was in the back keeping the girls entertained as we touched down for a visit to First Flight. I had them take a snapshot of me next to the airplane with the monument visible in the background—to this day the only photo of my airplane in my office, although a little faded now. And while my oldest daughter just graduated from college and the youngest finished her freshman year in college, it feels like the airplane, First Flight, and I haven’t changed at all. I still think I look like that young man in the photo, and the airplane still looks the same—on the outside. Inside, with a new interior and new glass cockpit since the last visit, the old girl looks a lot different.

One significant change to the First Flight landscape is the addition of the “pilot shack,” which AOPA funded as a gift to pilots in advance of the 2003 centennial of powered flight. Although we at AOPA call it the pilot shack, it is not a shack at all, but a modern facility complete with much welcomed restrooms for pilots and the public, and a flight planning room with computers and charts. Access to the room is restricted to pilots by the use of a keypad, with the code noted as the “VFR transponder code.”

In looking through my photos from that 2001 trip, I found one of me talking to Park Ranger and Historian Darrell Collins. Collins, a lifelong resident of the Outer Banks, is known around the world for his mesmerizing telling of the Wright brothers’ story on the Outer Banks. I’ve heard him tell the tale at banquets and events numerous times since, and was privileged to hear it again this year as he kept a group of AOPA visitors spellbound for an hour—including walking us from the Wright Flyer replica in the museum out to the rail from which the brothers launched their fragile flying machine on December 17, 1903.

First Flight is a magical place where time seems to stand still, and we can reflect on how far aviation has come in such a short time. A landing at First Flight should be on every pilot’s bucket list. If you’re lucky you’ll be there on a day where Collins is your host.

Editor in Chief Tom Haines flies his Bonanza A36 for business and pleasure.

Email [email protected]