You’ve heard of a runner’s high: a state of euphoria that comes from pushing through perceived limits. But when I run, pain just produces more pain.

I understand the concept, though, because I slide into a cockpit and blast through the sky, rolling and diving, wheeling and spinning, straining and grunting, sweating and swearing—all for a game of chase. So I can relate to the runner, fidgeting through the last of the day’s meetings, eyeing the clock, just waiting for the moment he can get his fix.

I thumb the mic switch, full of anticipation, eager to experience the rush I only get while under the crush of six times the force of gravity. “Cleared to maneuver!” On my nose, a couple hundred feet ahead, my friend, known as “Bones,” acknowledges by rolling his navy blue Yak 50 inverted, then pulling into a split-S. The chase is on. I roll inverted, pull hard on the Yak’s tall stick, and crane my head up, giving me a fantastic view of Mother Earth straight down through the bubble canopy.

I pick up Bones’ Yak streaking below me in the opposite direction, 6,000 feet above the Southern California desert. As I pitch down, I see his nose coming up. We’re at opposite ends of a loop and as my wings carve against gravity, I watch him soar gracefully high above, silhouetted against the clear blue sky. Keeping the back pressure on the stick I strain through the Gs, eyes locked on the Yak perched above, calculating the angle to close the gap.

Dancing hippos

I left military flying a few years ago, and at the time I didn’t want to go. Walking out for my last flight was like stepping into an operating room to have my healthy legs removed. Something that had been all-consuming for my entire adult life was going to be cut away forever. I was reluctantly being transformed into a “former fighter pilot.”

I got over it, sort of. With time my experiences and memories from that world began to feel as though they belonged to someone else. A type of flying that I had spent years dreaming about and attempting to master had been excised. I told myself it was time to grow up.

I managed pretty well until a friend dragged me to a flying afternoon with his Yak buddies. I didn’t believe that anything with a propeller could approach the thrill I had known flying afterburning jets. I felt like a former pro ball player invited to play in a rec league. It could never be as good as it was, so why get involved? The answer is a love of the game, and the pursuit of the runner’s high.

The -50 was designed by Sergei Yakovlev, son of the legendary Alexander Yakovlev, founder of the eponymous plant and hero of the Soviet Union. The Yak 50’s warbird lineage is easy to trace to Alexander’s Yak 7 and Yak 9 fighters, which were stamped out by the thousands during World War II and were instrumental in driving the Germans from the Motherland.

Yak 50s were distributed to Soviet paramilitary flying clubs, where they were flown hard and often. In the mid-1980s, Progress began manufacturing Yak 55s, which rendered the 50s obsolete. Clubs were ordered to scrap the older airplanes, and sadly most did. Today fewer than 100 Yak 50s are flying globally.

The group of Yak pilots I fly with is an eclectic band hewn together from formation clubs, competitive aero-batic circles, and former military pilots. The flying we prefer is, without a doubt, esoteric. It doesn’t transport the sick or needy, bring business partners together, or take families on vacation. It is the empty calories of aviation, a 100LL cupcake. That said, it is exactly the type of flying the Wright brothers envisioned when they were enviously watching the birds chase each other around the bicycle factory. This is the type of flying that inspired human flight, in all its magnificent variety. We combine the basic disciplines of formation flying and competitive aerobatics into a free-form game of tail-chase. It is a thrilling, high-energy, three-dimensional roller coaster.

The Yak 50 is the steed of choice for its warbird lineage; the fact that it’s far less expensive than other aerobatic aircraft of comparable performance; and its Experimental category, which allows for upgrades and modifications to airframes, engines, and avionics. But the real reason for our devotion to this airplane is its unparalleled performance in aerial dogfights.

The feature that rendered the 50 obsolete in competitive aerobatics is what endears it to us—the shape of its wing. The 1980s brought a sea change in competitive aerobatics with multiple “outside” or negative-G maneuvers that required symmetrical wings which could fly as well inverted as right-side up. A Pitts, Edge, or Extra can perform exquisite outside loops, but the Yak 50 with its flat-bottom wings is at a big disadvantage. For our seriously whimsical game of tail-chase, however, the Yak 50 has no peer.

The crush

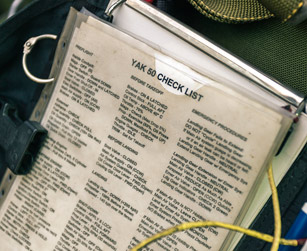

On this day a few of us met up with Bones at his home airport. I pay attention as he briefs with the casual meticulousness of someone who has been down this road many times before but still treats the situation with the respect it deserves. He finishes and we sip coffee, waiting by the open hangar door for the sun to burn through the low overcast. We’ve already prepped the Yaks, topping off the oil in the hungry radials and making sure we have all the fuel we can carry. As sunlight starts to break through, we begin the complicated shuffle that kicks the M14P engines to life. Wiping sweat from my forehead despite the morning chill, I mash the start button while pumping the primer lever. The engine roars to life in a cloud of white smoke and an invigorating rumble.

Bones calls for taxi and I follow him to the hold-short line. It’s difficult to see over the long nose so the Yaks snake back and forth like sidewinders. I take my side of the runway and give the instruments one last glance. All in the green, here we go.

In the practice area, we warm up with a few hard turns to ensure our airplanes and bodies are ready for the Gs. We start off easy as I follow him through a series of wingovers and barrel rolls. I lock my eyes onto his airplane and try to block out the rest, keeping the sight picture constant. After a few minutes later he queries, “You ready?”

Bones sets us up at 6,500 feet msl. I maneuver into position 300 feet behind him and listen to his countdown. “Three, two, one, go!” His airplane cranks left and about 30 degrees down. I wait a couple seconds, until the angles look right, then chase him. He continues his pull up and over the top in a tight loop and I fix my gaze onto the blue airplane as I feel the Gs build. My goal is to fly cleanly, and pull to the limits without stalling. I step on the rudders instinctively, working to keep the long nose tracking straight through the relative wind; right foot on the way down, a boot full of left on the way up and over the top. We go around four times, then five, and six: weightless over the top, grunting across the bottom.

I kept my focus on the blue airplane alone, barely registering the passing of earth, sky, earth, sky. After what seems like an eternity, he eases his pull as he points straight up. He is going to try to outmuscle me in the vertical. I ease up just slightly to preserve energy. I’ve got to hang on the blades long enough to intercept him on the way down. High above me he pivots on a wing tip while I wrestle the controls to keep from stalling. As the blue Yak flashes past heading down, I throw in full left rudder and aft stick. My Yak half snaps and I fall right back into place.

“You ready for lunch?” Bones asks on the radio.

I’m drenched in sweat, exhausted, and my neck is sore, but I couldn’t be happier. Halfway through a burger I’ll be itching to get back up, and feel the crush and the rush all over again.

Francesco “Paco” Chierici flew Navy A–6, F–14, and F–5 aircraft and produced the documentary film Speed and Angels.

Photography by Mike Fizer

When I first set eyes on the Yak it did nothing to alter my preconceived notions. It had a propeller: strike one. No one would ever describe it as sleek, stylish, or ergonomic: strike two. Compared to the sleek lines of an Extra or Edge, the Yak 50 looks like a tractor from a Ukraine collective farm. The Yak burps and snorts like the beast with which it shares a name. Oil slobbers from the twin exhaust stacks. On the ground, it shows the worst of its Soviet DNA.

But it only took one flight for me to change my mind. Now, when I walk up to a Yak 50, I see a vehicle designed specifically for the delivery of endorphins, with rugged good looks and a warbird pedigree. Once airborne, this crude beast turns into something amazing and unexpectedly graceful, like the dancing hippos in the movie Fantasia. The Yak 50 is a true pilot’s machine whose sweet spot is magically revealed when back pressure is applied to the stick. As the big prop bites counterclockwise into the air, the pilot feeds in increasing left rudder and the sturdy wings carve an amazingly tight circle in the sky.

The crush of Gs pushes you firmly onto the seat-pack parachute and you emit a satisfied groan as the spinner points to the heavens. Temporarily unburdened from gravity, aggressive deflections of the huge ailerons, elevators, and rudder allow the Yak to pivot gracefully. For a moment, hanging weightless, you can look down on the world with the perspective of an eagle waiting to pounce. Eventually time unfreezes and the wind rushes over the camber once again as the big radial seeks the earth. At the intersection of the appropriate airspeed and back stick, the Gs build again and you know the Yak is ready to pitch back up for the next maneuver. It’s as nimble in the air as it is brutish on the ground.

No peer

Part of the Yak 50’s mystique is its story. A mere 312 were pieced together in a Soviet helicopter factory, improbably named Progress Arsenyev Aviation Company, in the town of Arsenyev in far eastern Russia. Since 1936 the factory has continuously built machines of war for the Soviet and Russian governments. Yet somehow in 1975 the factory was tasked to build a revolutionary airplane to achieve global domination in international aerobatic competition. The Yak 50 succeeded spectacularly. In 1976, the Soviet men’s team placed first, second, and third—and the women captured the top five spots.