Midair spurred modern ATC

Grand Canyon crash site designated national landmark

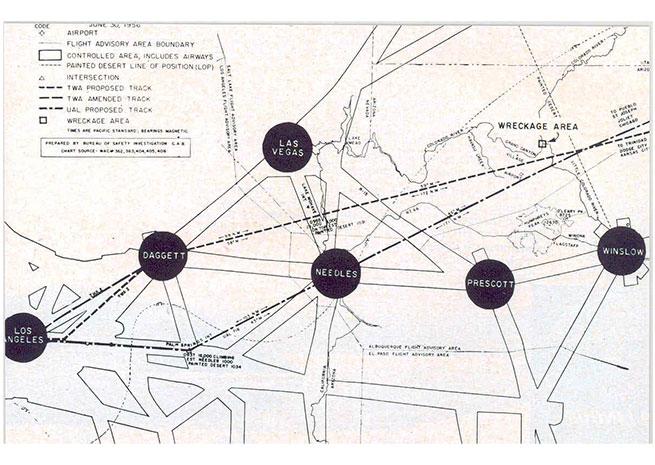

On June 30, 1956, two airliners departed Los Angeles about three minutes apart, charting courses that would intersect over the Grand Canyon. Their collision at 10:31 a.m. led directly to modernization of the National Airspace System as pilots know it today.

The Trans World Airlines Super Constellation and United Airlines DC-7 carried 128 people between them, and all aboard perished in what remains among the deadliest midair collisions in history. The crash, then the latest in a growing number of midair collisions that took place in increasingly crowded postwar skies, proved a painful lesson that convinced Congress to reverse a trend of budget cuts and finance air traffic control modernization.

The crash site has now been designated a national historic landmark.

The U.S. Department of the Interior announced the landmark designation April 23, one of four such sites across the country added to the list of places significant to the nation’s history and heritage.

In 1956, civilian aviation was under the purview of the chronically under-funded Civil Aeronautics Administration, and huge swaths of the nation were not covered by radar. Controllers relied on aircraft position reports and routing along a much smaller number of established airways to maintain separation. At the time, according to an online account published by the FAA, both pilots opted to depart controlled airways in favor of more direct routes that would include a scenic overflight of the Grand Canyon. Both were cleared, and instructed to maintain VFR. Controllers had initially denied the TWA crew’s request for 21,000 feet, noting that the United flight was nearby at the same altitude. The TWA crew requested a “1,000 on top” clearance, similar to a modern “VFR-on-top” clearance.

"ATC clears TWA 2, maintain at least 1,000 on top. Advise TWA 2 his traffic is United 718, direct Durango, estimating Needles at 0957," was the recorded response, relayed through a contractor. The aircraft course lines would intersect over the Painted Desert, about half an hour later.

The Civil Aeronautics Board, a precursor to the NTSB, determined the probable cause of the crash was that the “pilots did not see each other in time,” adding it was not possible to determine exactly why. Building cumulus clouds may have interfered with the pilots’ vision, normal cockpit duties or an attempt to give passengers a more scenic view may also have caused distraction. The report also noted inadequate ATC facilities and a lack of personnel may have also contributed to the disaster. Within months of the crash, CAA began setting up new radar installations, ordering 23 new long-range systems for $9 million, the single largest purchase by the agency at the time. Civilian use of military navigation systems was also instituted in 1956, with the crash helping settle debate between reliance on civilian distance measuring equipment (DME) and the military tactical air navigation (tacan) system. Airlines had delayed purchasing new equipment while the debate was ongoing, and the final compromise created the vortac system, where civilian aircraft would continue to use VOR stations for direction-finding, but use the military tacan instead of DME for distance measuring.

The Federal Aviation Agency was created as an agency under the Federal Aviation Act of 1958 (also the first year that the number of transatlantic air passengers exceeded the number traveling by sea) later becoming the administration of today upon creation of the Department of Transportation in 1967.

The National Park Service noted in its news release that other modern safety systems including flight data recorders and collision avoidance systems trace their roots to the 1956 crash.