P&E Never Again: When push comes to shove

Engine failure at 800 feet

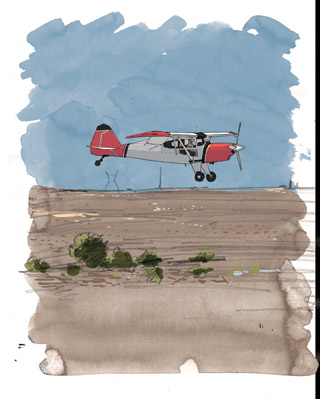

A few years ago, I became interested in buying a Bearhawk—a homebuilt Experimental aircraft very similar to a Maule. With only about 70 made, finding one for sale is not easy, so when I saw an ad for one I thought I could afford, I jumped on the opportunity to check it out.

A few years ago, I became interested in buying a Bearhawk—a homebuilt Experimental aircraft very similar to a Maule. With only about 70 made, finding one for sale is not easy, so when I saw an ad for one I thought I could afford, I jumped on the opportunity to check it out.

As an A&P, I performed my own prepurchase inspection. After a full day of pulling cowls, inspection covers, floors, et cetera, and completing a thorough checkout, I finished with a squawk list of about 100 items—some of which were serious safety-of-flight concerns. This was a plans-built aircraft, and much of the work was appallingly substandard.

Still, I wanted a Bearhawk, didn’t think I’d find another, and convinced myself that if I got it for the right price, I might be able to fix the deficiencies and come out ahead. With that in mind, I spent a second day repairing those items that I judged to be the minimum required to allow a safe test flight. I went up with the owner for about an hour and found it to be a decent-flying airplane. I wanted to do a few stalls, but he was uncomfortable with the idea, claiming that he never ever did them. He said I would have to go up alone if I wanted to complete that portion of the test flight. I landed, dropped him off, and quickly took off again. At about 800 feet agl, the engine quit.

Prior to this incident, I had read several articles and blogs about the “impossible turn”—opinions and theories about turning back to the runway versus landing straight ahead after an engine failure on departure. As a result, in my previous airplane (a Bellanca Scout), I had practiced the maneuver at high altitude, over an airport, and had noted how much altitude was lost getting turned around and lined back up with the runway.

Through my experimentation I had decided that an aggressive, steep turn, with a correspondingly aggressive drop of the nose, gave the best results. (I believe it was Barry Schiff who outlined the procedure in this magazine.) Based on my trials, I had set my own personal minimum of 500 feet in my Scout or a similar aircraft for trying to turn back; below that I would land straight ahead, or perhaps execute a much smaller turn to a landing area. I drilled on the “big push”—the technique required to prevent a stall when the engine suddenly gives up the ghost in a steep climb.

My point in the relating all this is to emphasize that I felt prepared, and perhaps was more prepared than most for this potential failure.

So, what did I do when it actually happened? I forgot the most basic precepts and almost failed.

I don’t have a clear recollection of what went through my mind when the engine quit, but I do know that I immediately began a 180-degree turn back to the runway. I do remember that my heart was pounding, and I was thinking something along the lines of “keep it together, don’t screw up the downwind landing” (this is a tailwheel aircraft). About halfway around the turn, I suddenly noticed that the stick was getting very mushy. I instinctively pushed forward on the stick and shot a look at the airspeed indicator—this is the first time that I had even thought to do so; when I did, the needle was just about at the bottom! Luckily for me, the forgiving Bearhawk wing kept flying long enough to gain some airspeed and complete the turn. The landing itself was uneventful.

I spent Day Three tearing into the airplane to figure out why the engine had quit. It turned out to be an error in the fuel system design (the builder had deviated from the plans) such that fuel flow to the engine would be interrupted anytime the airplane was in a steep climb with less than half-full tanks.

So what’s the lesson? That when push comes to shove, we’ll quite possibly fail to do the right thing, despite all our training and practice? That’s a tempting interpretation, and I thought that way myself for a while, but I believe the truth is more subtle. Despite the fact that I almost forgot to follow the most basic rule of airmanship—keep flying the aircraft, no matter what—all that practice had allowed me to recognize the feel of an airplane on the edge of stall (the mushy stick) and know what to do (push forward aggressively) to get it flying again. I think this was by then deep in muscle memory, and that’s likely what saved me. For me, the real lesson is that the more you practice these maneuvers, the more likely that when you need them, you’ll do them just well enough to succeed.

Lesson two is not to let an emotional attachment develop that clouds your judgment about an aircraft purchase. With all the problems I found on the inspection, I should have walked away without flying the airplane. Even though I fixed the items I considered most critical, I missed the fuel system design problem, and perhaps others I would have discovered later.

Finally, I was prompted to write this after watching a double-fatal stall/spin after an engine failure during a go-around. The pilot could have pushed forward, turned 90 degrees, and landed on the crosswind runway. He didn’t. Any of us could have made that mistake. Practice these emergency maneuvers until your responses are automatic. When it happens, you might not have time to think it through. AOPA

Andy Young has approximately 3,500 hours and flies for an air taxi in Alaska. He currently owns a Maule with a properly built fuel system.

Web: www.aopa.org/pilot/never_again

Digital Extra: Hear this and other original “Never Again” stories as podcasts every month on iTunes and download audio files free from our growing library.