They rose before dawn and scraped ice from wings before launching into the Iceland sky to circle a volcano spewing gouts of red lava.

Haukur Snorrason, whose father, brother, uncle, and nephew are also pilots, captured images on Sept. 4 and 5 showing a dramatic eruption at close range. Once authorities determined the eruption is producing very little in the way of abrasive ash, the primary threat to aircraft, Icelandic pilots were cleared to approach as close as they dare.

“If it gets hot inside the cockpit, you are too close,” Snorrason wrote in an email (adding a wink). “When this eruption first started the whole area was closed to all air traffic, but when the scientists saw what kind of eruption this was they opened for flying.”

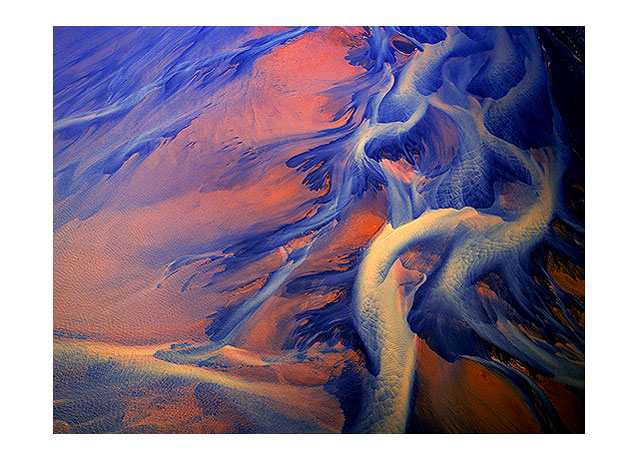

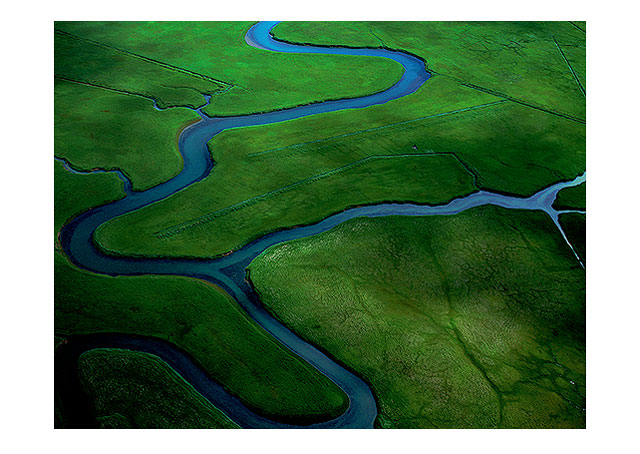

Snorrason and his brother, Jón Karl Snorrason, co-own a Jodel D.140C TF ULF, a 180-horsepower taildragger well suited to backcountry flying in a country where the backcountry accounts for most of the country. Iceland’s population is concentrated on the coast, while inland the volcanoes help shape some of the most visually striking scenery on the planet.

“If you have a major ash cloud like in Eyjafjallajökull volcano 2010 which disturbed all the air traffic you have to keep more distance,” Snorrason wrote. “But bear in mind we live in a country that has eruptions every 4-5 years so no one is over stressed when these things happen.”

“If you have a major ash cloud like in Eyjafjallajökull volcano 2010 which disturbed all the air traffic you have to keep more distance,” Snorrason wrote. “But bear in mind we live in a country that has eruptions every 4-5 years so no one is over stressed when these things happen.”

Snorrason set out for the Holuhraun eruption early in September, not long after the massive eruption began. (The eruption produced by mid-October the largest lava flow documented on the island in two centuries.)

Flying the five-seat Jodel, the Snorrasons were able to land and camp a 10-minute flight from the volcano, allowing them to loiter far longer than most sightseers. The nearest commercial airport is about an hour’s flight away. They slept under the northern lights and woke to return for more photographs, and video. The video taken by Snorri B. Jónsson, Jón Karl Snorrason’s son, co-owner of the Jodel and a pilot for Icelandair (as his father and grandfather were), is shown below.

Haukur Snorasson offers photographic tours of Iceland, showing professional shooters and enthusiastic amateur photographers some of the island nation’s most striking scenery. He learned to fly at age 22 (in a Cessna 152), but followed his father’s footsteps into photography rather than into the professional pilot ranks. (Snorri Snorrason was among Iceland’s most prolific aviation photographers; his work can be viewed online.)

“Photography was my thing,” Haukur Snorrason wrote. (His name, by the way, translates to “Hawk” in English.)

Snorrason wrote that those French-built Jodels (he previously co-owned and flew a smaller model) are good photo platforms despite their low wing. Many of the photographs he sells to calendar publishers. Photos in two books of Iceland photography that Snorrason has published so far are taken from the air. Snorasson said the Jodels offer a steady platform.

Snorrason wrote that those French-built Jodels (he previously co-owned and flew a smaller model) are good photo platforms despite their low wing. Many of the photographs he sells to calendar publishers. Photos in two books of Iceland photography that Snorrason has published so far are taken from the air. Snorasson said the Jodels offer a steady platform.

“It has a stick that I put between my knees while photographing, so I steer with my knees, very easy,” Snorrason wrote—even though a few degrees of bank are needed to keep the wing out of the shot.

General aviation in Iceland is an expensive pursuit. Avgas, Snorrason reports, costs about $10.50 a gallon (based on current prices and currency conversion rates).

“Our main enemy however is the ever changing weather,” Snorrason wrote. “You hardly (ever) get the same weather conditions all over Iceland.”

About the size of Kentucky and located just south of the Arctic Circle, Iceland’s climate is moderated by ocean currents bringing warm water from the south. Though temperatures can be mild for such a high latitude, the wind is another matter.

“Iceland has to [be] one of the most windy places on earth,” Snorrason wrote. “It has often been said that Icelandic pilots are often better prepared when they start their career than many others because of the difficult conditions. So you need to ambush these good flying days you get, and use them to the fullest.”