Wings over Asia

Home stretch on the trip of a lifetime

Photography by the author, Air Journey, and Keith Abela

Because of the need for dispatch reliability and the rather ambitious itinerary, weather factors, and the distances involved, nearly all of the pilots who take Air Journey’s around-the-world trip fly turboprops or jets.

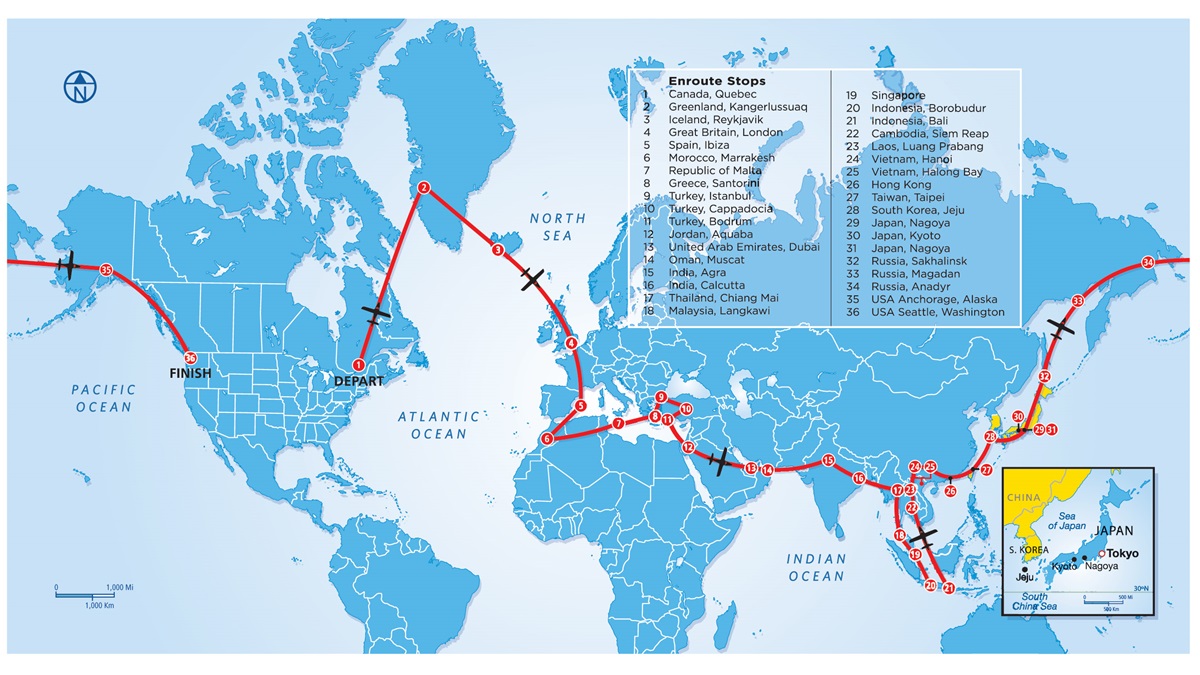

Back in 2008, I was lucky enough to fly along on the first legs of Air Journey’s first-ever around-the-world (RTW) trip, from Quebec City to Paris, via Nuuk, Greenland; Reykjavik, Iceland; and Inverness, Scotland. This year, my luck held once again. Only this time I flew legs closer to the home stretch, on legs from Hong Kong to Taipei, Taiwan; Taipei to Jeju, South Korea; and Jeju to Nagoya, Japan.

“The trip of a lifetime” is a superlative that’s often way overused. But not when it comes to an Air Journey RTW. Great food, five-star hotels, epic sightseeing, and lifelong camaraderie are key features. And so is the attention to flight planning, as well as overflight and other permits, which Air Journey handles for you. It’s all part of a 76-day odyssey that takes owner-pilots to 40 airports in 29 nations. The price? $88,000 per person, which covers hotels and most meals—but not fuel.

The company on this year’s RTW was as impressive as it was genial. Jimmy Hayes of Atlanta flew his PC–12, along with former airline pilots Danny and Laura Azara. David and Betty Schlacter of Peoria flew their TBM 850. Flying their Sierra-modified Citation ISP was Bill and Corinna Hettinger of Tampa. And Brad and Deborah Howard flew their Twin Commander 690B, along with son Scott. My wife Sylvia and I flew with Air Journey founder and President Thierry Pouille. Perhaps best of all, I got to log six hours of left-seat time in Pouille’s Cessna Mustang.

Flying foreign. Here in the United States, takeoffs and landings are comparatively simple. But overseas flying can throw you some serious curveballs. As soon as I arrived at Hong Kong’s Peninsula Hotel for the next day’s trip briefing, I was hearing stories about arrivals to the Hong Kong International Airport. Apparently, the drill is to fly at no less than 230 knots until reaching the final approach fix, and then make a frantic effort to slow down and descend for the landing. No doubt about it, Hong Kong has to be one of the busiest airports in the world—and it seems the only way to make it all work, there and elsewhere, is for the controllers to slam-dunk everyone as fast they can.

Then there are the language issues. Yes, English is the international language of aviation, and controllers do give it their best—but, to cite but one example, a Burmese controller kept asking for what sounded to the pilots like “maknum.” Thinking it was a request for each airplane’s Mach number, the group dutifully answered, only to have the request repeated. Turns out the controller wanted an estimate to an intersection he couldn’t properly pronounce. Speaking of estimates, radar coverage can be spotty in far-flung airspace, so position reports and ETAs to fixes are often requested.

Engine start times are additional overseas novelties. We’re used to firing up and calling for our clearances. But in places like Hong Kong and Taipei, the drill is to call ATC for permission to start engines. This can be a pain when you’re sitting in the cockpit and it’s 92 degrees with humidity to match, but it does save you fuel and it does help traffic flow at busy airports—especially when your allotted “slot” time for takeoff keeps getting delayed because of congestion.

Then there are transition altitudes and levels. Here, we have one altitude where we change our altimeters to standard pressure—18,000 feet. But elsewhere, transition altitudes (when climbing into the flight levels) and transition levels (when descending out of them) vary.

Handling. Other formalities include not just creating and filing flight plans, but obtaining overflight permits for crossing into each nation’s airspace, securing and paying for landing permits and fees, plus obtaining takeoff slot times. Oh, and you also need to arrange for going through customs and immigrations procedures. You conceivably can do all this by yourself, but it could drive you nuts in the process. Luckily, Air Journey does the flight planning and handles all the rest through a network of handlers. Like Misao (“Mickey”) Nagae, our handler in Nagoya. When we all landed, Nagae was there to speed our way through the bureaucratic hoops—one of which involved a health officer beaming a temperature detector at our foreheads. Got a fever? Then you’ll be quarantined!

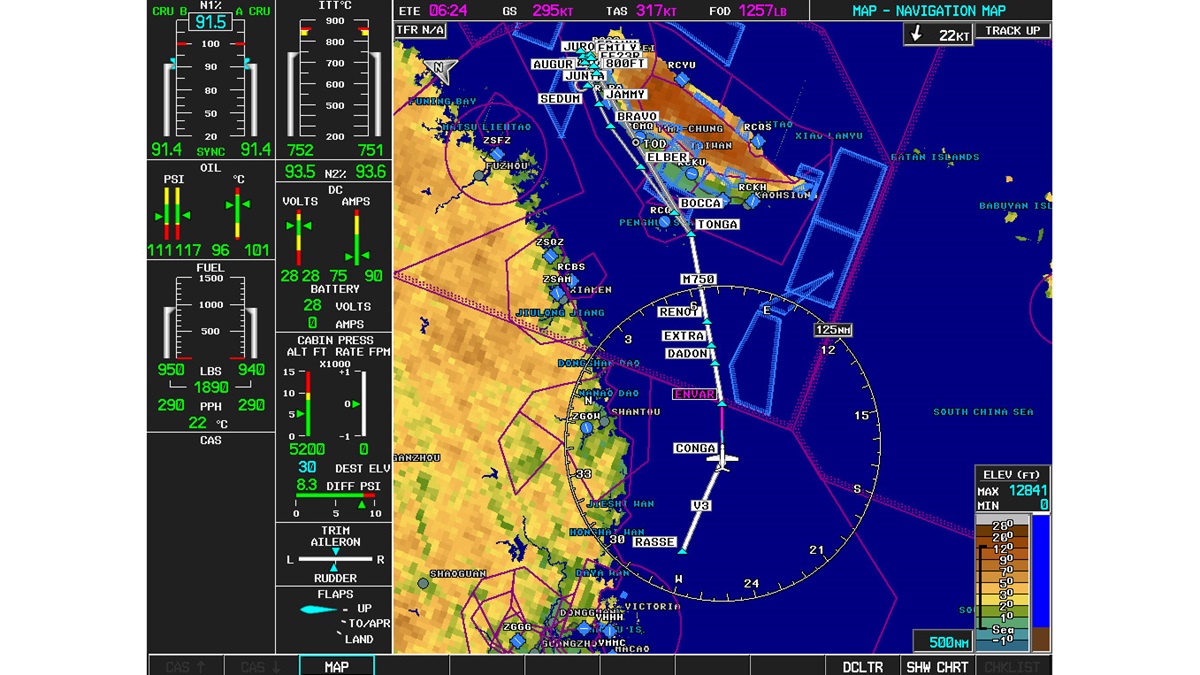

Stick time. The night before a flying day, there’s a detailed pilot briefing about the upcoming route, so there’s little surprise about what’s to come. For the departures at Hong Kong and Taipei, all the pilots had to wait for engine start times—and the Mustang’s was delayed by 30 minutes in steam-bath heat and humidity. But, by turns, we were cleared for takeoff between jumbo jets. The standard instrument departures (SID) were remarkably simple. At Hong Kong International (VHHH), it was a 180-knot climb to 14,000 feet to Ocean intersection, followed by a direct climb to FL330 following a 435-nm route that carefully avoided the Chinese mainland.

The only issues for the Mustang were the much higher-than-standard conditions (ISA +19 degrees) prevailing that day. The 180-knot climb speed (160 knots is more customary) didn’t yield an optimal climb rate, so it took us longer than usual to reach cruising altitude. And once there, we registered a 309-knot true airspeed; under standard conditions that speed would be more like 340 knots. So a slight change in ambient temperature can mean big changes in performance.

A mere one hour, 22 minutes later, the island of Taiwan appeared beneath a shelf of broken skies.We were assigned the ILS Runway 23R approach to Taipei’s Taoyuan International Airport (RCTP) and after an uneventful landing, the group quickly cleared customs and immigration at the Taiwan Business Center FBO, then got in the van, bound for the Grand Hotel Regent Taipei Hotel.

For the 576-nm, one hour, 48-minute leg from Taoyuan to Jeju International (RKPC) in South Korea, each airplane departed at five-minute-slot intervals. Our Mustang went first, and, despite ISA +17 conditions, we reached FL330 in a respectable 30 minutes, although we scrapped the original FL370 cruising altitude because it would have taken more time getting there. And here are the numbers for the cruise to Jeju, which are very similar to our performance on all the East Asia legs at FL330: 178 KIAS; 309 KTAS; and a total fuel burn of 580 pph (about 86 gph).

After landing at Jeju we taxied past a “follow me” truck to out parking spaces—hard by several 747-400s!—passed customs, and into the van bound for the hotel.

You’ve probably noticed that these legs lasted no more than two hours, covering approximately 500 nm each. That’s by design, to minimize fatigue, ensure adequate fuel reserves, and leave more time for fun at each stop. The whole itinerary is also optimized for the best weather. The RTW trips take place in the more climatologically benign months of the year. For the North Atlantic and European segments, May and June are usually free of winter’s ice and low ceilings. As for the Mediterranean legs—well, this area is nearly always tame. The desert regions are predictably dry, and by June and July the worst monsoons affecting South and Southeast Asia haven’t kicked in quite yet. And for the East Asian legs I flew, typhoon season hasn’t really spooled up yet—although we did manage to dodge typhoons Rammasun and Neoguri, the first of the season.

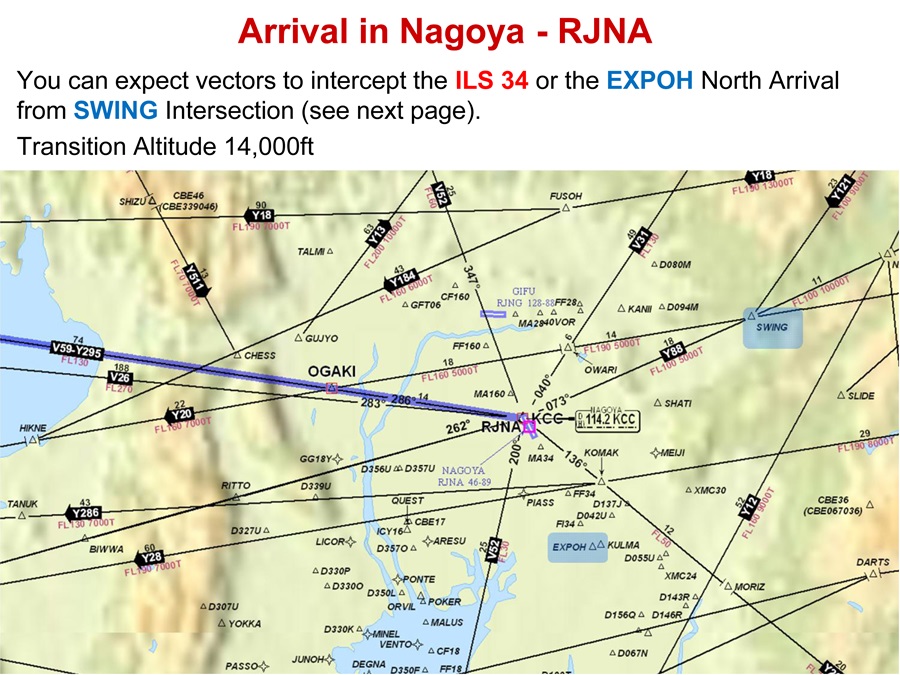

We flew the 527-nm leg to Nagoya (RJNA) at FL330 again, and once more the trip was a short one—one hour, 39 minutes. As usual, Bill and Corinna Hettinger took the high road, flying their Sierra-modified Citation ISP up at FL430. The Schlacters’ TBM flew at FL290; the Howards’ Twin Commander took FL270 on that leg; and Hayes’ PC–12 flew at FL250-270, where it would make its best speed. Using 123.45 MHz, each ship stayed in contact with the other, sharing weather and wind information.

Flying the ILS to Nagoya’s Runway 34 I felt a reassuring familiarity with the airplane. We might be in the Orient, but most terminal procedures have the same feel worldwide, and there’s a comfort in that. So it was 60-percent N1 and flaps 15 while maneuvering to intercept the localizer, gear down at one dot above the glideslope, then 50-percent power and full flaps while riding the pipe at 98 knots, then the VREF of 91 knots approaching the threshold. Pull back the power halfway as you cross the approach lights, then go to idle once over the runway. With any luck it’ll be a gentle “erk” as the mains touch down.

Stepping out the door to meet Mickey, it finally sank in. My time on the trip was coming to an end. But no matter. A bullet-train ride to visit Japan’s original capital, Kyoto, was waiting. More so than ever, I realized just how fortunate I am to be a pilot, to have been on such an epic voyage, and to have had such outstanding company.

Email [email protected]

Fun facts

- 29 nations visited, 100 flight hours, from May 11 through July 26, 2014

- 76 days’ duration (Quebec City, Canada, to Seattle, Washington)

- 28,971 nm flown; 291 knots average groundspeed

- Average leg: two hours; 500 nm

Distances:

- Longest leg: 875 nm, from Aqaba, Jordan, to Bahrain

- Shortest leg: 188 nm, from Dubai to Muscat, Oman

Fueling facts

- The Mustang burned approximately 8,000 gallons of Jet-A

- The TBM 850 burned approximately 5,000 gallons of Jet-A

- Average fuel price on the trip was $4.50 per gallon

- Pilots pay for fuel using UVAir cards. Air Journey secures the fuel releases, which ensures that adequate fuel is available at each stop.

- The simplest way to pay for fuel? Cash

Asian Attractions