Standard instrumentation is designed around the concept of redundancy. Pitch, roll, and yaw all have primary and secondary references on the panel, and each works just a bit differently. The chief source for information on level flight is the altimeter. This instrument may look and act somewhat like a clock, but it reads altitude instead of time.

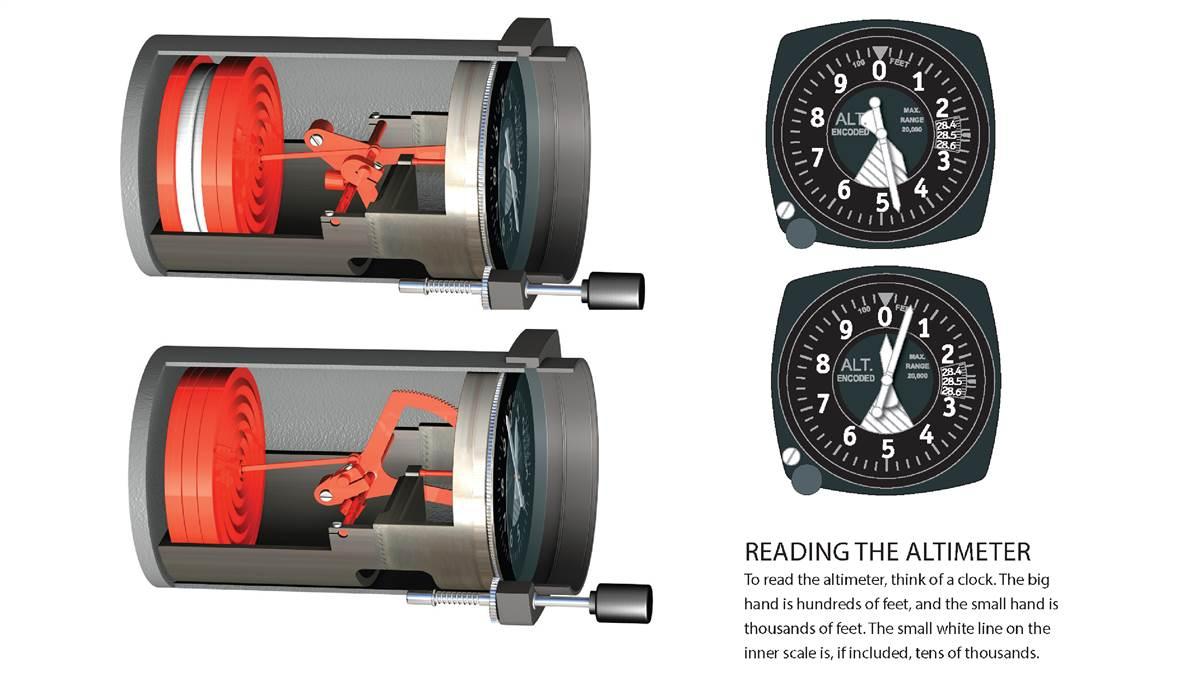

The altimeter works on a basic principle. As you ascend, air pressure decreases. The instrument senses this by taking the ambient air pressure from the static port. That air is plumbed through the back of the panel and into the back case of the altimeter. Inside the altimeter is a sealed disc called an aneroid, or bellows. As the aircraft goes up, the pressure inside the case decreases and the bellows expand. As the aircraft descends, the opposite happens. The bellows are mechanically connected to the face of the instrument through gears.

The altimeter works on a basic principle. As you ascend, air pressure decreases. The instrument senses this by taking the ambient air pressure from the static port. That air is plumbed through the back of the panel and into the back case of the altimeter. Inside the altimeter is a sealed disc called an aneroid, or bellows. As the aircraft goes up, the pressure inside the case decreases and the bellows expand. As the aircraft descends, the opposite happens. The bellows are mechanically connected to the face of the instrument through gears.

The Kollsman window on the front of the instrument allows the pilot to set the altimeter to the current local pressure. Without an adjustment, the altimeter would be subjected to pressure changes as a result of weather, and not just a change in altitude (see “Weather: It's Not That Simple,” p. 50).