A student pilot and instructor are cruising on the first leg of a dual cross-country flight. The first checkpoint, a two-runway airport, is in sight, and the student pilot is getting ready to log the time overhead, when the instructor declares, “Engine fire!”

A student pilot and instructor are cruising on the first leg of a dual cross-country flight. The first checkpoint, a two-runway airport, is in sight, and the student pilot is getting ready to log the time overhead, when the instructor declares, “Engine fire!”

There’s a checklist for that. For a 1980 Cessna 152, it is a six-step procedure calling—in a true emergency—for the mixture to be set at idle cutoff, fuel valve off, master switch off, cabin heat and air off (except wing root vents), airspeed 85 knots indicated, and a forced landing performed according to the checklist for an emergency landing without engine power.

The procedure also notes, “if fire is not extinguished, increase glide speed to find an airspeed which will provide an incombustible mixture.”

This scenario is just one example of a situation in which an emergency descent may be called for. The emergency descent is a flight-test item: Task A, Emergency Operations, in the Private Pilot Practical Test Standards (PTS).

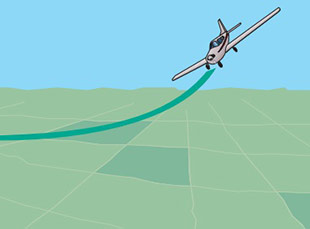

“An emergency descent is a maneuver for descending as rapidly as possible to a lower altitude or to the ground for an emergency landing,” explains Chapter 16 of the Airplane Flying Handbook. (It’s one of two references listed in the PTS for studying the maneuver. The other is your pilot’s operating handbook)

“The need for this maneuver may result from an uncontrollable fire, a sudden loss of cabin pressurization, or any other situation demanding an immediate and rapid descent. The objective is to descend the airplane as soon and as rapidly as possible, within the structural limitations of the airplane. Simulated emergency descents should be made in a turn to check for other air traffic below and to look around for a possible emergency landing area.” Make a radio call to alert any aircraft nearby.

Performing the maneuver in a turn avoids imposing excessive negative loads on the airframe. “When initiating the descent, a bank of approximately 30 to 45 degrees should be established to maintain positive load factors (‘G’ forces) on the airplane,” the chapter explains. Training should follow the manufacturer’s recommended configuration and airspeeds.

Don’t overlook that detail about structural loads in the surprise of a simulation or a checkride. A key objective of the maneuver’s demonstration is to verify that the pilot “maintains positive load factors during the descent.”