The mark to point you home

His essential problems are set him by the mountain, the sea, the wind. Alone before the vast tribunal of the tempestuous sky, the pilot defends his mails and debates on terms of equality with those three elemental divinities.

—Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in Wind, Sand and Stars

I have never been lost in the sky.

I have never been lost in the sky.

There have been times, though, when it was possible. When I was learning to fly, heading aloft with just a sectional, a paper flight plan, and an E6B, there were days when the winds would change and a landmark I was expecting on the right side of the airplane would appear far to the left. I know the ground here pretty well, so I would smile, a bit nervously; adjust my course; and carry on. No worries at all.

My pilot friends tell stories of flying low enough to read names on city water towers. I’m sure it’s more imagination than history. But in winter, when snow covers the prairie so deep that lakes and rivers and railways disappear with the fields and farmsteads, I am grateful for GPS and the moving map. There is something poignant and deep about searching a landscape for the familiar, the mark to point you home.

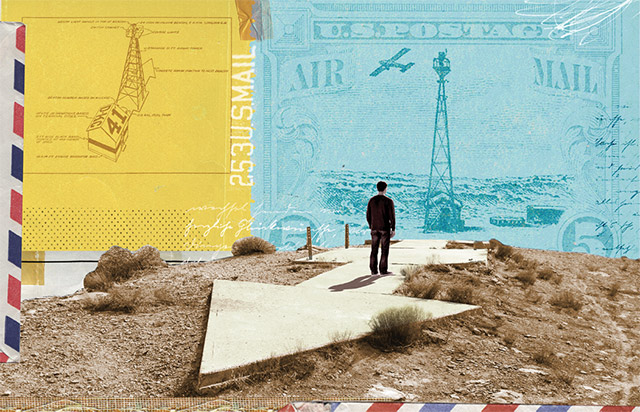

On the west side of Albuquerque, New Mexico, on a bright and already hot Thursday morning, in a valley as flat as my prairie, my boots scrape past silver leaf nightshade, globe mallow, brittlebush, and sage. My Jeep is parked on sandy ruts a quarter-mile behind me. On the lookout for snakes, I step over rabbit holes surprisingly wide and deep.

In truth, though, all I can think about is being lost in the sky. Elvis fans to go Graceland. Some pilots go to Kill Devil Hill. For me, the necessary pilgrimage is here. I am searching for the remains of Beacon 68, once part of a network that guided early airmail pilots from coast to coast. I can imagine that type of flying, imagine the hope and the fear. There were 1,500 beacons, more or less. They turned on top of 50-foot towers. There were no charts. No reports of winds aloft. There were instructions to follow a river, follow a line of bluffs, keep the lake on your left, look for the roof of a school, follow the beacon lights. Connect the dots. Lose your way and you could lose your life.

I know the beacon is gone, fallen, rusted into the desert dust. What I am really looking for is the arrow.

I live near an old airmail route. Minneapolis to Fargo to Winnipeg. Reading history, I learned there once were barns with arrows painted on the roofs to guide the pilots. But when I would go flying to find one, I never did. When someone asked if I had heard about the old beacons and the concrete arrows, I had to say I had not.

Four steel posts rise out of the brush, the feet of the old beacon tower, each one set in the corner of a concrete square. Sage breaks the concrete open. On the west side, the concrete narrows—the shaft of the arrow—and then there is another, smaller square for the tail. This is where a shack housed a generator and supplies. On the east, the concrete narrows again, and then broadens to the shape of a pointer. Fifty feet from one end to the other, I think. A lizard scuttles from one bush to another. My foot finds an old can, rusted beyond age. There is no sound of propeller in the sky.

I have seen this spot on Google Earth. I have set the elevation to 500 feet agl, 1,000 feet, rarely more. Even when the arrow was painted bright yellow, it would have been far too small to find from the sky. Yet it wasn’t the arrow that was supposed to be found. That was the purpose of the light. Once you got here, the arrow pointed the way. There are high mountains to the northeast. The Sandia Range. The arrow points vaguely east, toward a pass, toward safety, toward the next light and the next bit of help.

I stand where the beacon used to be and look down the arrow’s path. Bright blue sky and cottonball clouds. I wonder how many pilots smiled at this turn, banked their ship to follow the sign, their letters and cargo safe so far. Then I wonder how many pilots never made it here.

I have never been lost in the sky. But I know how easy it can be. This, I think, is the place to give thanks.

W. Scott Olsen is a regular contributor to AOPA Media.