Wind streaks on the upper Mississippi River show a steady southeast wind as Wipaire’s newest Boss 182 descends toward the textured water surface.

“This power setting is just fine so there’s no need to change anything,” says Brian Addis, a Wipaire test pilot, as he coaches me through my first water landing in the St. Paul, Minnesota, company’s newest creation—a beefed-up, amphibious Cessna 182 with a growling Lycoming IO-580 engine and three-blade Hartzell propeller. “Keep what you’ve got [16 inches of manifold pressure] all the way to touchdown.”

After a flare, a chirp from the stall warning horn, and a few rapid-fire slaps from waves hitting the bottoms of the amphibious Wipline 3000 floats, the Boss 182 settles into the middle of a mile-wide stretch of the river.

I bring the power to idle and start to deploy the water rudders to turn downwind, but Addis assures me that more takeoff distance isn’t required—even on a sultry day, with a steep-sided bluff straight ahead.

“We’ll be off the water in eight seconds,” he says. “We’ve got plenty of room.”

Water rudders up, flaps 20, prop and mixture full forward, and cowl flaps open. I add full power and stand on the right rudder as the airplane surges forward.

Addis recommends full back yoke until the Boss 182 claws its way onto the step, and then release the back-pressure completely. The Boss 182 splashes through the water in a 15-degree nose-up attitude, and at 40 KIAS slight forward pressure results in a quick airspeed jump to 45 KIAS. Light back-pressure lifts the airplane off the water as the airspeed builds.

We are carrying almost full fuel (92 gallons capacity/88 usable) and two adults, a load that puts the airplane near its forward center-of-gravity limit. But the Boss 182 climbs at 1,000 fpm at 80 KIAS with the flaps at 20 degrees. The climb rate diminishes slightly as I dial the prop rpm back to 2,500, raise the flaps, and accelerate to 100 KIAS.

We level off at 2,500 feet msl, and the airspeed indicator shows 120 knots at 75-percent power (25 inches of manifold pressure and 2,500 rpm) while consuming 17.5 gallons of avgas per hour. Then we head back to the river for another landing.

“Floatplane pilots always want more performance, and that’s the Boss 182’s strong suit,” Addis says. “These numbers speak for themselves.”

Transformation

The Boss 182 began as a Cessna 182—but it’s really meant to be a replacement for aging Cessna 185 Skywagons that have been backcountry stalwarts for decades, as well as float 182s. And the updated airframes offer some real advantages.

The Boss 182’s cabin is 2.5 inches wider than the 185, and its Lycoming IO-580 engine is more powerful than the Skywagon’s stock 260-horsepower engine—or the coveted 300-horsepower upgrades.

The Boss 182 also addresses the main shortcomings of standard float 182s: a paltry useful load and restrictive center-of-gravity limitations. The Boss 182 provides a gross weight increase to 3,500 pounds (from 3,100), and useful load rises to 950 pounds (from 650).

“The 182 has always been a nice, stable floatplane,” Addis said. “But full fuel and two adults in the front seats would put the CG beyond the forward limit. And for a four-place airplane, the useful load is nothing to brag about.”

Wipaire addresses these restrictions by acquiring steam-gauge Cessna 182S and -T models built from 1997 through 2004. Unlike earlier versions, the S and T airplanes were made with full factory corrosion protection—a major consideration for floatplanes.

When Wipaire starts a conversion, technicians remove the engine, prop, interior, Plexiglas, and wings. Then it puts the wings in jigs and add structural reinforcements and stall fences for the gross weight increase. Each airplane gets a Hartzell three-blade composite prop, paint, a rudder extension, a new engine mount, a new interior, and an upgraded instrument panel that includes a Garmin GTN 750, GDL 88 (for Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast In and Out), digital engine monitor, and PS Engineering 8000B audio panel. G500 glass panels are an option.

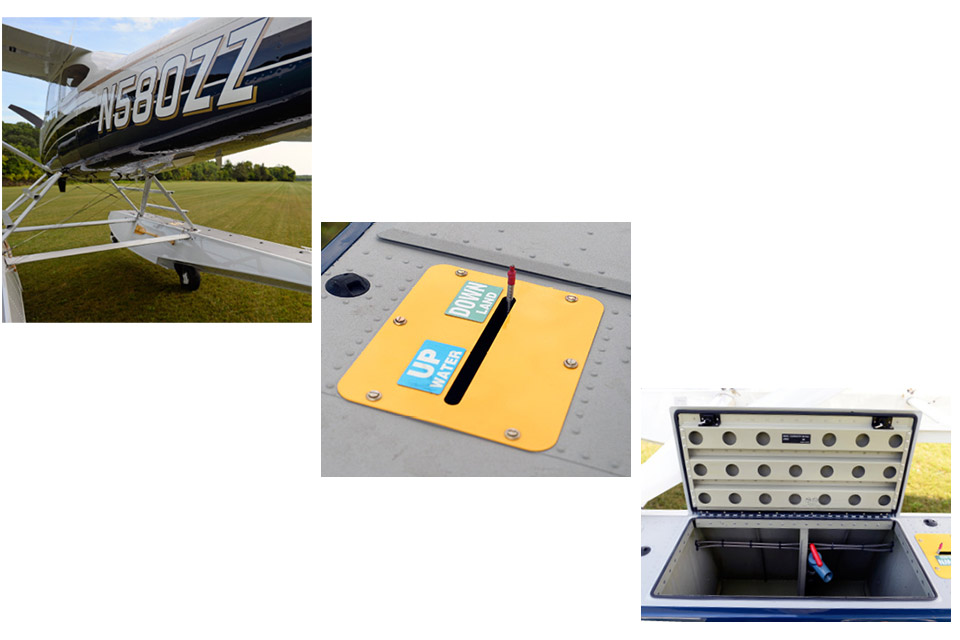

Every Boss 182 also comes with Wipaire’s patented laser gear warning system that senses whether the aircraft is over land or water and audibly warns the pilot to “Check gear!” if the wheels are down less than 50 feet over water, or up less than 50 feet over land.

The wing-mounted laser is similar to those used by surveyors. It emits a beam that water absorbs and hard surfaces reflect. The system knows the position of the landing gear and activates when it senses a mismatch between the landing surface and gear position. (At press time, the company was still awaiting FAA approval of its software to activate the laser systems.)

“We have no doubt it will save lives and reduce insurance costs,” Wipaire CEO Bob Wiplinger said. “The systems are installed in every Boss 182 we’ve sold. We’re just waiting for approval to turn them on.”

The entire transformation from stock airplane to Boss 182 takes about six months, and Wipaire has converted five airplanes so far. Retail prices range from $450,000 to more than $600,000, depending on options. The company also intends to market wheel versions of the Boss 182 beginning late this year or in early 2016.

“The first post-conversion test flights are done on wheels—and the performance is pretty spectacular,” Wiplinger said. “People step out of the office to watch, because they’re not used to seeing a Cessna 182 climb almost vertically like a helicopter.”

A hard pull

Ready for takeoff on South St. Paul Municipal Airport’s Runway 16, with a quartering 10-knot headwind blowing from left to right, I set the flaps to 20 degrees, hold the brakes, and advance the throttle. “Be ready to use lots of right rudder,” Addis cautions. “This engine and prop pull hard.”

At brake release, the combination of the airplane’s natural tendency to weathervane into the wind and p-factor require the pilot to hold full right rudder through the first half of the 800-foot takeoff roll, and moderate right rudder during the climb.

The fact that the main wheels are well aft of the airplane’s center of gravity requires a firm pull on the yoke at rotation speed. The nosewheels come off the pavement, and the rest of the Boss 182 soon follows.

Even though we’re staying in the traffic pattern for several circuits, Addis advises raising and lowering the landing gear each time to reinforce the habit. Abeam the touchdown point, I lower the landing gear, and a gravelly recorded male voice lets me know the wheels are down for a hard-surface landing. (A recorded female voice comes on when the landing gear is up for a water landing—and the contrast in voices is meant as a cue to pilots about the different landing surfaces.)

I trim for 75 knots and 20 degrees flaps, and carry about 16 inches of manifold pressure into the landing flare. The main wheels touch down, and I increase back-pressure on the yoke to bring the nosewheels down gently.

Full flaps can be used for steeper approaches, but the airframe is plenty draggy with the wheels down and 20 degrees of flaps. Also, the intermediate flap setting simplifies go-arounds—an important consideration in all of Cessna’s bigger piston singles because of their tendency to pitch up at full power, combined with the nearly full nose-up trim many pilots use on final approach.

An achievement

The Boss 182 is a highly refined aircraft that is so much more capable than a stock Cessna 182, it’s hard to compare them. And really, the more meaningful comparison is with the Cessna 185 it’s designed to replace.

The Boss 182 does everything a Cessna 185 can do, and more, in a comfy, stylish, modern package. Its powerful engine/prop combination makes it a real four-seater, and it has the speed, range, and carrying capacity to fill the gap between existing piston singles and larger, far more costly turboprops (and turboprop conversions).

Also, the Lycoming IO-580 seems like an excellent engine choice. The aerobatic version of the same powerplant is highly regarded among manufacturers of Unlimited aerobatic airplanes like the Extra 330 series for both its reliability and high torque—considerations that are vital to floatplane pilots, too.

Wipaire’s selection of relatively late-model 182s for upgrades makes sense, too. It’s hard to find older 182s that are corrosion free, and the fact that the S and T models were built with rust-inhibiting zinc chromate on every metal part—and stainless steel hardware—helps ensure they will stand up to the rigors of water flying. Many of the original engines are timed out or facing repetitive crankshaft airworthiness directives, so a conversion could be timely.

Wipaire spent nearly a decade planning the Boss 182 and getting FAA approval for its myriad alterations. What the company produces isn’t a refurbishment—it’s a totally transformed airplane. The Boss 182 is so different from its former self that it’s hard to believe they share the same numerical designation.

“Pilots have really got to get in the left seat and feel the power and all the engineering we put into this,” Addis says. He’s got a point. The prop is lighter, yet it outperforms the original and is far quieter than a two-blade. The new engine is bigger and heavier than the one it replaces, yet the airplane has more payload and a broader CG envelope.

It’s sad to see iconic Skywagons disappearing after their decades of superlative service. The Skywagon may be the best, most versatile utility airplane ever made. But at least there’s some consolation in knowing that a modern substitute is available for those looking for similar performance.

And both utility airplanes reflect their times. The 185 was a Jeep; the Boss 182 is a designer-edition Grand Cherokee.

Email [email protected]

SPEC SHEET

Cessna/Wipaire Boss 182S/182T

Price as tested: $615,000 (182T)

Specifications

Powerplant | Lycoming IO-580-B1A

315 bhp stock

340 bhp as tested

Recommended TBO | 2,000 hr

Propeller | Hartzell Trailblazer carbon fiber HC-F3YR-1AN/NG8301-3

Length | 29 ft 6 in

Height | 13 ft

Wingspan | 36 ft

Wing area | 174 sq ft

Wing loading | 20.1 lb/sq ft

Power loading, as tested | 10.29 lb/hp

Seats | 4

Cabin length | 8 ft 11 in

Cabin width | 3 ft 6 in

Cabin height | 4 ft 0.5 in

Empty weight | 2,550 lb

Empty weight, as tested | 2,550 lb

Max ramp weight (land) | 3,510 lb

Max dock weight (water) | 3,482 lb

Max gross weight | 3,500 lb

Useful load | 950 lb

Useful load, as tested | 950 lb

Payload w/full fuel (182T) | 438 lb

Payload w/full fuel, as tested (182T) | 438 lb

Max takeoff weight (land) | 3,500 lb

Max takeoff weight (water) | 3,472 lb

Max landing weight (land or water) | 3,350 lb

Fuel capacity, std, 182S | 92 gal (88 gal usable)

Fuel capacity, std, 182T | 92 gal (87 gal usable)

Oil capacity, ea engine | 11 qt

Performance

Takeoff distance, ground roll (land) | 987 ft

Takeoff distance over 50-ft obstacle (land) | 1,836 ft

Takeoff distance, water run 1,258 ft

Takeoff distance over 50-ft obstacle (water) | 2,465 ft

Max demonstrated crosswind component | 13 kt

Rate of climb, sea level | 1,009 fpm

Max level speed, sea level | 125 kt

Cruise speed/endurance w/45-min rsv, std fuel (fuel consumption) @ 75% power, best economy | 118 kt 6,000 ft (15.8 gph)

@ 65% power, best economy | 118 kt 6,000 ft (14 gph)

Service ceiling | 14,150 ft

Absolute ceiling | 15,708 ft

Landing distance over 50-ft obstacle (land) | 1,411 ft

Landing distance, ground roll (land) | 650 ft

Landing distance over 50-ft obstacle (water) 1,733 ft

Landing distance (water run) | 869 ft

Limiting and Recommended Airspeeds

VX (best angle of climb) | 60 KIAS

VY (best rate of climb) | 83 KIAS

VA (design maneuvering) | 129 KIAS

VFE (max flap extended) | 104 KIAS

VLE (max gear extended) | 170 KIAS

VLO (max gear operating) | Extend 170 KIAS, Retract 170 KIAS

VNO (max structural cruising) | 129 KIAS

VNE (never exceed) | 170 KIAS

VS1 (stall, clean) | 58 KIAS

VSO (stall, in landing configuration) | 41 KIAS

For more information, contact Wipaire Inc., 1700 Henry Avenue, South Saint Paul, Minnesota 55075; 651-451-1205; www.wipaire.com.

All specifications are based on manufacturer’s calculations as published in the airplane flight manual supplement, are calculated at max gross weight with no wind and average piloting skill, and do not reflect performance gains from porting, polishing, and flow balancing. Increased performance is possible with advanced pilot technique and skill. All performance figures are based on standard day, standard atmosphere, sea level, gross weight conditions unless otherwise noted.

Extra

Wipaire offers the Boss 182 with a Lycoming IO-580 that produces 315 hp from the factory, and up to 340 hp with optional port and polish. AOPA flew the 340-hp version.

What’s old is new

Remanufacturing programs breathe new life into older airframes

Refurbishments can give pilots access to high-quality aircraft at a fraction of the cost of factory-new airplanes, and even—as is the case with the Boss 182—raise the airplane’s performance standard far beyond anything the original manufacturer could have envisioned. AOPA launched its “Reimagined” aircraft restoration program and supports similar efforts to showcase restored aircraft as a viable option to brand-new ones—especially in the training market. Aviat, Premier Aircraft, Redbird, Sporty’s, and Yingling Aviation all are refurbishing Cessna trainers with many modern improvements.

AOPA’s Reimagined aircraft, remanufactured and sold by Aviat, set a high standard for remanufacturing an existing aircraft to as-new condition. Each airframe is disassembled and thoroughly inspected, and then painstakingly rebuilt using new pulleys, cables, wiring, and hardware. The engines are overhauled, interiors replaced, panels modernized, all instruments are overhauled or replaced, and they all include current GPS navigation systems and digital radios. The airplanes also are backed by their restorer with warranties.

With the cost for brand-new training aircraft topping $400,000, flight schools, clubs, and individual owners must have alternatives. Reimagined aircraft and other refurbishments are showing the way with aircraft of exceptional quality, usually at less than half the cost of factory-new airframes.

Wipaire has been a pioneer in this area by not only restoring existing airframes, but enhancing them with more power and new technology. The company also does total makeovers on Cessna 206s and Caravans, among others.—DMH