He’s been called the “super repo man” and once starred in the first season of a Discovery Channel reality show called Airplane Repo. He is an “aircraft repossession specialist” who never finished college but who has a net worth of more than $2 million, drives a Bentley, chain smokes cigars, and owns the oldest aircraft repossession service in the world. He chose to follow only one piece of the advice that his father gave him, and got his pilot certificate at the age of 16—being a pilot “might come in handy,” his father said. He flew for Braniff International Airways for a while but he found it boring.

For Nick Popovich it all started when a bank loaned a company enough cash to buy a couple of Boeing 747s. The new owner, it seemed, had stopped making payments, and stopped maintaining the jumbos. Some of the bankers knew Popovich and asked if he’d like to take part in a little adventure.

Popovich tracked the airplanes to an airport in Asia, rounded up a couple of crews, and headed east. He explained to airline employees that they were there to perform a typical inspection, so they were allowed to make sure both 747s were airworthy; they fueled them up, fired up the engines, and filed flight plans to Australia. “By the time they figured it out we were gone,” Popovich says. From Australia they flew to Mojave, where the bank had prearranged storage, and Popovich collected his check. “That paid a lot more than I expected,” he says. “I decided there was a business there.”

That was 1979. He formed sage-popovich, inc. (SPI)—Sage is the surname of his ex-wife—to repossess commercial aircraft. The first 10 years he was on his own. “I’d get a call and I’d round up some friends, and it was an adventure,” he said. But business grew, and now, with more than 1,600 repossessions, it’s the world’s largest specialist in the recovery of aviation-related equipment.

That was 1979. He formed sage-popovich, inc. (SPI)—Sage is the surname of his ex-wife—to repossess commercial aircraft. The first 10 years he was on his own. “I’d get a call and I’d round up some friends, and it was an adventure,” he said. But business grew, and now, with more than 1,600 repossessions, it’s the world’s largest specialist in the recovery of aviation-related equipment.

Whenever there’s a recession or a natural or man-made disaster, business picks up: after the first Gulf War in 1991, post-9/11, the Great Recession. “I kind of look at European traffic patterns to see how well the airlines are doing,” he says. Although the airplanes are not always maintained, SPI still has an agreement with the bank to operate safely. “We’ve had a couple of situations,” he says. “Nothing major.” An Airbus A320 out of Thailand suffered a minor hydraulic problem, so they landed in the Azores to replace the brake valves, and there was an engine problem on a Gulfstream G200—but “nothing traumatic or dangerous or scary,” he says.

This comes from a guy who spent a week in a Haitian prison.

In 1986 a nuclear reactor in Chernobyl, Ukraine, suffered a meltdown, and the airline business took a deep dive. One skipped a few payments on an airliner thought to be in the Dominican Republic, so the bank hired Popovich to look into it. He flew to Santo Domingo with a flight engineer and two mechanics, but when they arrived the airliner wasn’t there. Popovich tracked it to Port au Prince, Haiti; drove to that airport; and told the airport manager it was their airplane.

“He was kind enough,” Popovich says. “But for the airplane being parked there for a few months, they wanted a million dollars. We called the bank and told them to wire it there, and we went to the airplane. The airport manager sent along five or six kids with machine guns to watch while his mechanics inspected it, and an airport mechanic airstarted the engines. I gave him some cash and told him if he came back at two o’clock in the morning I’d give him more money.”

They waited until the mechanic showed up at 2 a.m. Once both engines were running, Popovich advanced the throttles, and taxied fast to the end of the runway and started his takeoff roll. Four thousand feet away the truck with the machine-gun kids blocked the runway. The airliner didn’t have enough speed to make it over the truck. He swerved off the runway and rolled into the weeds. The machine-gun kids shot through the engines and bayoneted the jet’s fuel cells, while Popovich hopped out of the airliner and yelled for them to stop. “I push one of them,” he says, “and he and his buddies beat the hell out of me.”

Popovich regained consciousness in a small cell with a wire-mesh ceiling and 35 prisoners crammed inside. “I met with the guys from the U.S. embassy, and the Haitians wanted $100,000 for bail,” he says. “I didn’t know anyone who would pay it for me, the bank least of all.” Seven days later, rebels overthrew Haitian President Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier and the city erupted in chaos. “Someone threw open the cell door,” Popovich says. “I ran to the Sheraton downtown. The hotel was kind of in chaos. Everything was goofy. I helped myself to a room and I arranged for a friend to pick me up.” The next day he was back in the states.

“The other guys scattered when I was getting beat up,” Popovich says. “I’m still in touch with them. I don’t blame them. We had decided beforehand it was every man for himself.” What if Baby Doc hadn’t been overthrown? “My guess is I would still be there, rotting,” he says. The airplane was only worth between $400,000 and $500,000, after all.

“My definition of scary has changed since I was younger,” he says. “I’m not as crazy as I was when I was 30 years old.” Today SPI has assembled a worldwide database of 4,000 pilots, each rated from highest to lowest by how much time in type, how much transatlantic time they have, and how much transpacific time. From that database a crew is assembled. Most repossessions go smoothly. “I have an agreement with the bank not to breach the peace,” Popovich explains. In other words, he approaches the delinquent borrower, tells them he’s repossessing the jet, and the borrower tends to give up without a fight. Then they work together to assemble maintenance logs.

The lender has already scanned the logs during the prepurchase inspection, while the airline has kept the majority up to date. “One time a pilot wanted $25,000 for them, and I said, ‘We’ll call the FAA and say you’re trying to extort me,’” he says. The pilot handed over the logs free of charge. “I love when they try to extort money from me. It’s a federal offense to do that—not to mention if they do it over the telephone, it’s wire fraud,” he adds. “They generally see the light.”

Once in a while they have to get an attorney involved. And while English is the official language of aviation, that doesn’t extend to record-keeping or airport staffs. “A lot of places like France or South America don’t have lot of English speakers in the corporate world,” he says. On his only repo in China, for instance, he had to hire someone to translate the logs. But otherwise, no trouble from China.

So have 25 years and 1,600 repossessions changed Nick Popovich?

“I think it’s maybe made me more compassionate,” he says. “It’s taught me a lot of humility. I repossessed two airliners from a Greek airline that put 300 people out of work. It’s not an easy thing to do.” From that experience he realized it’s better to negotiate when he can. “Lately I’ve been preaching this to the seller,” he says. “Instead of repossessing, let’s negotiate something.”

Phil Scott is a freelance writer and pilot living in New York City.

A day paved with silver

Popovich’s company works with helicopters, too

One of Nick Popovich’s biggest undertakings is also one of his most famous. When helicopter flight training and air tour company Silver State Helicopters was outed as a pyramid scheme for its greedy owner and abruptly closed its doors on February 3, 2008, Popovich was called in to literally pick up the pieces.

With dozens of locations nation-wide, repossessing Silver State’s aircraft and other valuable assets took a coordinated effort. To make it happen Popovich rounded up a staff of more than 100, and used roughly 125 flatbed trucks to repossess more than 240 helicopters. It took just 24 hours. There also were dozens of cars, some airplanes, simulators, and office furniture.

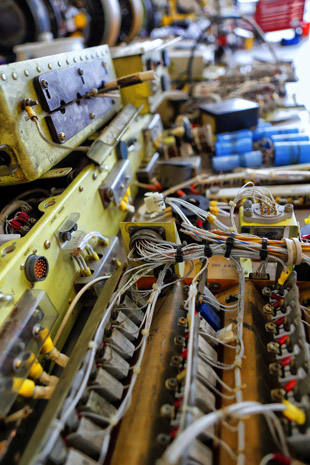

Popovich took the helicopters to Sky Helicopters in Texas and the rest of the aircraft inventory to his facility in Indiana, where it was parted out for the banks. —Ian J. Twombly