Here we are in the depths of winter, and what’s that? A mention of an advancing warm front in your preflight briefing? Good news, you might think, temperatures will soon be on the rise. This warmth will surely dissipate any fog or low clouds and banish icing from any upcoming airmets. But despite their promising name, warm fronts in the colder months can mean some of the worst flying weather.

To be sure, cold fronts can also bring dangerous conditions. But cold fronts travel faster and often affect less area than warm fronts. They tend to come on strong, and then move along after a day or two. Warm fronts move more slowly and typically cover vast regions of the United States. In winter this spells big trouble.

Warm fronts are created when low-pressure centers draw warm, moist air from the South or Southeast. Because this air is warmer and less dense than the colder air ahead of it, it rides up and over colder air masses in a process that meteorologists call overrunning. As this overrunning air is lifted, it cools with altitude and forms clouds—thin layers of high-altitude, ice-crystal-laden cirrus at first, followed by successively lower levels of stratus clouds. By the time the surface position of the warm front is reached—this is marked on surface analysis charts with a red line adorned with red, semicircular symbols—you’ll likely find low instrument meteorological conditions with snow, rain, or freezing rain, and visibilities compromised by mist and fog.

Sound like a mess? You bet it is. We now have a situation in which any precipitation may fall from a large, warmer slice of the atmosphere into the cold air beneath it. It’s important to remember that warm and cold, as always, are relative terms here. The temperatures above a warm frontal surface may be a mere five to 10 degrees warmer than the cold air below—and below freezing! So you should assume that any clouds associated with a winter warm front may well carry the potential for icing. That’s just one reason to make a detailed preflight check for freezing levels, airmets Zulu, and the current and forecast icing potential (CIP and FIP) charts; all this information is available on the icing tab of the Aviation Weather Center website (www.aviationweather.gov).

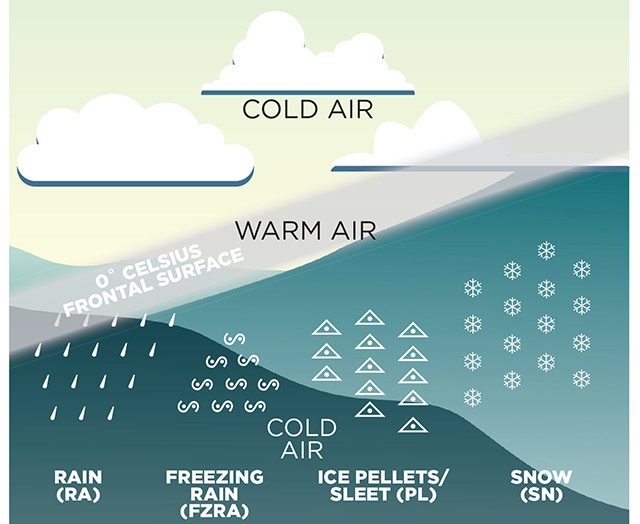

There’s always the chance of icing in clouds where temperatures range from plus 2 to minus 20 degrees Celsius (35 to minus 4 degrees Fahrenheit), and in warm front conditions you can see all forms of icing and winter precipitation. At the leading edge of a warm front, precipitation falling from stratus clouds may take the form of snow. If this snow falls through a thick layer of subfreezing temperatures, then it will remain as snow.

If any snow falls into layers with temperatures slightly above freezing, it will melt and then refreeze as ice pellets (sleet) if it encounters freezing temperatures on its way to lower altitudes. And if the next layer down is above freezing and very shallow—as thin as 1,000 feet, for example—then there’s not enough distance or time for any snow or ice pellets to remain in solid form, so there is melting into supercooled droplets. In worst-case situations, these droplets can take the form of large droplets or freezing rain, the most dangerous type of clear icing conditions.

Throw in multiple freezing layers, and you can see that winter warm fronts can pose the worst, and most far-reaching, winter flying weather. There can be every form of icing—clear, mixed, rime, and large-droplet—depending on the nature of the warm front’s vertical temperature distribution.

Here are some other considerations regarding winter warm fronts:

Don’t be fooled into thinking that adverse weather is localized around the surface warm front’s position, as shown on a surface analysis chart. Icing conditions can extend as far as 500 to 800 nautical miles ahead of a surface front’s position. Don’t believe it? Check satellite and radar imagery.

You often hear advice to climb in case you encounter freezing rain, the idea being that the rain originated aloft, in a layer of warmer air. True, but how thick is the layer of freezing rain? You’ll be icing up quickly during a climb, and the promised “warm” layer may be a thin, short-lived one.

Because warm fronts travel slowly, rain, ice, and snow at the surface can persist for days. Rain-saturated or snow-covered ground, together with cold temperatures, can combine to produce dense fog and low IFR (ceilings below 500 feet, visibilities below one statute mile) that will be reluctant to dissipate.

Ice protection systems—certified for flight into known icing, or not—can buy you some time to escape icing conditions, but they are not cure-alls. With warm fronts, ice-free weather may be hundreds of miles away. Ditto decent alternate-airport weather conditions.

Check your outside air temperature as you fly in clouds and precipitation. The worst icing—freezing rain and large-droplet varieties—occur near 0 degrees Celsius. Clear icing favors the 0 to minus-10-degree Celsius temperature band. Rime icing typically occurs between minus 10 and minus 20 degrees Celsius.

Geography is important. The Great Lakes, the Northeast, and the Pacific Northwest have the highest frequencies of large-droplet icing conditions because of their proximity to large bodies of water.

Warm fronts are usually to the east of a surface low, and oriented along a west-to-east line. Winds aloft are predominantly out of the south, and movement of the frontal weather is from south to north.

A warm front’s clouds and moisture can wrap around coastal lows and cause major snowstorms along the Eastern Seaboard.

Still want to launch into winter warm front conditions? Hey, you’re the pilot in command. Use your best judgment, which may dictate staying on the ground and watching that Terminator marathon you’ve been wanting to see.

Email [email protected]

Website of the month

Website of the month

Want to see some spectacular, high-resolution satellite imagery of weather systems and other Earth features? Check out the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) imagery on NASA’s earth data rapid-response website. Click on “MODIS Near Real-Time (Orbit Swath) Images” and browse away. Mouse over each image to see a red box identifying the photo’s position on the globe. Click on the 500-meter pixel size for truly breathtaking views. I’m hooked. —TAH

Web: http://earthdata.nasa.gov, search “rapid response”