P&E: Technology

Modernizing the FAA weather briefing

Your flight service station has changed

Did you know you can open and close a visual flight rules (VFR) flight plan via Email from today’s FAA flight service station? Prior to the flight, Lockheed Martin Flight Services—currently running flight service stations for the FAA under contract—will send you an “EasyActivate” Email, and when you are ready to take off you click on a link. The flight service system responds that your plan is activated. After your arrival, look for an EasyClose Email, click on the link, and a confirmation arrives that the flightplan is closed. Those are two of the changes you’ll find at today’s flight service station.

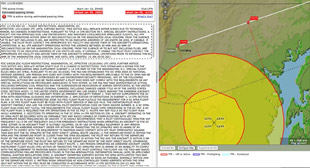

One of the more important chart overlays is a graphical representation of nearby temporary flight restrictions shown in relation to your course line. When I looked at my proposed route I was concerned.

There were two red flags—one at the starting point of Frederick and another 20 miles later; each had red dotted lines drawn to the red-coded boundaries of the Washington, D.C., airspace. Red borders meant that the airspace was active. Blue would have meant aerial firefighting was in progress, while light blue would have shown a scheduled but not active temporary flight restriction. I finally realized the graph was merely warning me my route would pass close to an area of flight restrictions, not that it would violate it.

As it turned out, I changed my destination to New Garden, Pennsylvania, thinking I might have lunch at the nearby Farm House restaurant located on a golf course. Sure enough, I got an Email 30 minutes prior to departure allowing me to open my flight plan to the new destination by clicking on a link.

I had filed a return flight plan before departure. If you call a briefer, the process is a bit easier. “We have a return button we hit and it populates most of the flight plan with the return data,” a briefer told me later. The briefer indicated the “return” button is an option for online users that Lockheed Martin is working on for the future. That’s the advantage of software-based briefings used not just by Lockheed Martin but by all the flight planning companies. If there are features you would like to see, let someone know and they might appear.

Email [email protected]

What’s next for DTC?

DTC (Data Transformation Corporation), headquartered in New York with offices in Maryland and New Jersey, was not one of the winners of the FAA’s new Direct User Access Terminal Services contracts. One of the company’s innovations was the “pushed” weather briefing, meaning a pilot could leave a request to be briefed on a route the night before a flight and receive the latest briefing the next morning. The contract ended in August, so what’s next for the aviation weather briefing company? At this writing DTC wants to stay in the pilot weather briefing game and is considering new offerings. The 50-person firm also sells financial software and has an independent contract with Harris Corporation for “back-end processing” for flight service stations in Alaska.—AKM

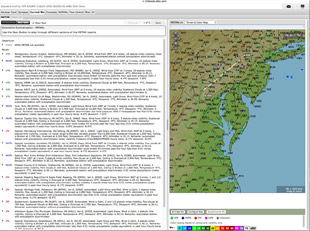

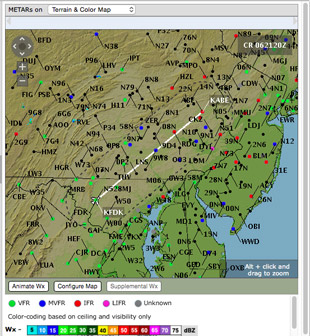

One of the new looks for flight service station online weather briefings is the color-coded weather summary. The proposed route is shown on the map and weather along that route within a corridor indicated by a dotted line is provided.

Color-coded dots in the map tell what the pilot needs to know at a glance. Green dots mean go—or visual flight conditions—blue means visibility or cloud height is not so good, but flyable. Red means you are going to need an instrument rating. Purple means your instrument skills need to be very sharp because conditions are poor.

The map shows restricted airspace in the Washington, D.C., and Baltimore areas, and its relationship to the author’s planned route (white line). A temporary flight restriction was in place and the red flags have the time of the restriction. Text (left) describes the details of the restriction.

CSC moves ahead.

Now that CSC (the 70,000-employee Computer Sciences Corporation, with multiple government and commercial products and services) has won a new FAA direct access terminal services contract, what’s next? (DTC, which formerly operated the program alongside CSC, will continue to operate independently.) The company will continue its services with the original 19-person staff, but will listen to what pilots need and propose new pilot weather briefing products to the FAA for approval as needed. CSC conducts 120 million activities with pilots each year, whether it’s closing a flight plan or a briefing, or 24 times as many as Lockheed Martin, the main contractor for FAA flight service stations. One of CSC’s most popular innovations over the years is its Tripkit that allows a pilot to carry all briefing and flight plan information into the cockpit. Another service is to update the pilot after a flight plan is filed with any changes proposed by air traffic control c before takeoff. That way, when a controller says he has a new routing, you already know what it is. —AKM

Chances are you didn’t know that because you use one of a half-dozen or more competing flight-planning services, including the new one just launched by AOPA with Jeppesen.

It’s time to take a look at what has happened to the FAA’s old phone and face-to-face briefings that many learned to use in decades past. Technology now grinds weather data into the answers you need for your specific route. The evolution has taken place over a decade but is no less important than GPS is to navigation and headsets are to clear communication.

Not only is the text and graphic data easier to understand, it is now specific to your route.

At today’s flight service station, you can open and close flight plans via Email and sign up for weather update Emails and other notices after the flight plan is filed.

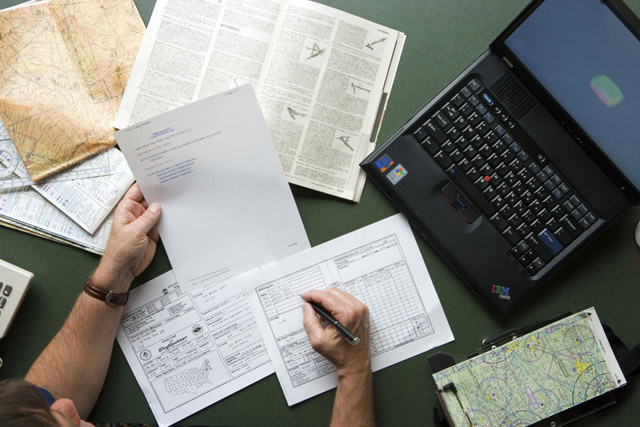

Here’s a real-world example. I originally planned a flight from Frederick to Allentown, Pennsylvania, but was stalled for days by bad weather. To test the system, I filed a flight plan online to Allentown every day for three days at lmfsweb.afss.com (the letters stand for Lockheed Martin Flight Services web) so I could get Emails about snow, freezing rain, fog, and high winds that characterized those particular days.

The flight plan was held for two hours after my proposed departure time and was automatically cancelled, so there was no penalty for filing a plan I knew I wouldn’t use. Not only did I get Emails about weather, but also about notices to airmen that popped up after my briefing concerning a runway that was closed at Allentown. The two notices hit my inbox as soon as I filed. I called a briefer to see why the runway closure wasn’t included in the online briefing minutes earlier, and he said the notices were issued just seconds after I finished. I would have departed not knowing one of the runways was closed had it not been for the Emails.

Nearly two dozen tabs on a single weather briefing page provide nearly all the information you’ll need—25 categories in all. Some are maps overlaid with current radar while others are graphic representations on a map such as weather warnings, temporary flight restrictions, and airport weather.

Before filling out the flight plan page, you’ll see on the home page weather for favorite airports you designate when you set up an account using your personal information and details about the aircraft you are likely to use. As I write this I am looking at the home page for my account, which lists my home airport, Frederick Municipal, as “low IFR, 4 statute miles visibility, ceiling is broken at 400 feet,” and a nearby airport, Eastern West Virginia Regional in Martinsburg, West Virginia, as “marginal VFR, 3 statute miles, ceiling is overcast at 2,900 feet.”

After registering, the next time you sign on and pull up the flight plan form many of the blanks about you and the airplane will be pre-filled. It works that way on the phone, too. If you call a briefer, caller identification will bring up information about you and your aircraft registration number. Your briefer may start the conversation with, “Is this November One-Two-Three-Four?”

That was the case on one of the days before my flight. In the text weather description, a graphic map showing color-coded dots for airports made my go/no-go decision obvious. The Frederick airport had visual flight conditions and its symbol on the map was green, but I would be unhappy because of the blue-colored marginal conditions by the time I reached Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and ready to turn around before reaching the red dot on the map representing Allentown.

Text weather descriptions appeared to the left of the map, but I didn’t even need to read them. Beside each text block was a color-coded summary; a red “IFR” for instrument flight rules, a green “VFR” for visual flight rules, and a purple “LIFR” for low instrument flight rules. There were no blue-coded marginal visual flight rules for cities along my route that day.

Expanding the map gave a broader picture of the situation; all the airports to the south of Maryland in Virginia and North Carolina were identified on a color terrain map with green dots, but red dots appeared for airports halfway along my route for Pennsylvania and neighboring states of New Jersey and Delaware.

It can even tell you that, for example, three-quarters of the way along your route weather will be bad, but if you depart say an hour early or an hour later, you can avoid it.