Help for your go/no-go decision

Entertaining information about worrisome traits that can launch you into a bad decision is available in the AOPA Air Safety Institute’s online risk assessment course. If you see yourself in any of the “bad” examples, you may want to utilize the risk-assessment guide the next time weather is less than desired for that flight.

The course takes all of 10 minutes, but uses videos, actors in role-playing scenarios, and safety statistics to explain how a desire to go isn’t the same as knowing that it is safe to go. The “Super Risk Advisor 3000” computer will share its reactions with you to proposed flights. In one, a Cessna 150 pilot plans a 100-degree-Fahrenheit afternoon flight from Telluride, Colorado, up—literally, up—to Leadville, Colorado. The density altitude is 14,000 feet. “So you’re kidding me, right?” the computer asks. “Wow!”

Another section lists a few risk factors that may get overlooked by the average pilot. When was your last flight? Are you current in the type of aircraft you’ll use? Are there any ifs, ands, or buts in the weather forecast? Is terrain friendly or unfriendly? What about the airport—are you heading for a short, narrow runway on an icy, windy day? And how much fuel is in the aircraft?

The point is made that airlines have rules to help make decisions that general aviation pilots may consider to be a matter of opinion. The airline pilot or crewmember’s working hours are clearly defined, while the general aviation pilot may decide to go and never consider the effect last night’s late party may have the following day. The pilot operating under Part 91 rules of the road knows it is legal to take off in poor visibility, but the airline pilot needs to have a departure alternate at the ready. Are you keeping to those personal minimums you’ve set, or are you willing to overlook them in order to stay on schedule? Can you easily land in 60 percent of the runway length, or will you need the entire length and hope for the best?

After reviewing those basic questions, the Flight Risk Evaluator portion of the course can be used for a quick check. It begins with two simple questions: Is this a day or night flight, and is it under visual or instrument rules? How you answer determines where the evaluation takes you next. Answering that the flight is a day-visual flight rules flight brings two more questions. Is it a local flight, and how many hours do you have? I answered “No,” for local flight, and put in my actual hours of 2,900.

After reviewing those basic questions, the Flight Risk Evaluator portion of the course can be used for a quick check. It begins with two simple questions: Is this a day or night flight, and is it under visual or instrument rules? How you answer determines where the evaluation takes you next. Answering that the flight is a day-visual flight rules flight brings two more questions. Is it a local flight, and how many hours do you have? I answered “No,” for local flight, and put in my actual hours of 2,900.

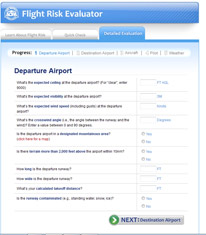

Those questions bring up a Flight Risk Evaluator form. On the form was a checklist suggesting at least a 3,000-foot ceiling, a minimum of five miles visibility, and a maximum wind of 30 knots including gusts. The crosswind limit should be only 75 percent of the capability of the aircraft, the form indicated.

Operational factors were divided into five categories: terrain, runway, aircraft, fuel, and recent experience. There should be no departures or arrivals in mountainous areas without contingency planning, the form indicated. There should be no terrain more than 2,000 feet above the departure or arrival airports within 10 nautical miles.

The runway, it was suggested, should be 50 feet wide and 50 percent longer than required by the pilot operating handbook. If the runway surface is contaminated by snow, ice, or rain, it should be 100 percent longer. The pilot should have 25 hours in type for single-engine aircraft, and 50 hours in type for multiengine or turbine aircraft.

The pilot should arrive with no less than a one-hour fuel reserve, the checklist noted. Also, the pilot should have flown 10 hours in the past 90 days, with six takeoffs and landings in the previous six months.

That’s the “Quick Check.” There is also a “Detailed Evaluation.” For that one, I indicated it would be a night flight under instrument flight rules. I was then asked how much instrument time I have, and how much total flight time I have. Optional questions included the type of aircraft, departure airport, and destination airport. I loaded up the example with minimal visibility, low ceilings, and high winds to see what the Evaluator would suggest. I would land, I said, with slightly less than an hour of fuel, had low recent experience, and had flown few instrument approaches in the past six months.

The Evaluator looked at 15 parameters, and gave me an “unsafe” reading for three of them: pilot recent experience, departure wind, and destination wind. I got a cautionary statement for icing, although none was forecast. I had indicated there would be rain, and the Evaluator indicated I needed to be aware of temperatures along the route. I also got a warning on fuel, because I was at or near the AOPA Air Safety Institute-recommended fuel minimum of one hour. A note indicated I should divert to a closer airport if my reserve dropped below an hour. On all other factors, including ceilings, terrain, runways, and visibility, I was given green check marks—meaning the circumstances met AOPA Air Safety Institute recommendations.

The course is a good reminder of aspects to be considered on any flight. When circumstances lead to nagging doubts about that next flight, see what the Flight Risk Evaluator has to say.

Email [email protected]

What the FAA says about automation

More than 30 pages of information on aeronautical decision making can be found in the FAA publication Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge. Along with discussions on health, judgment, and hazardous attitudes is a section on automation.

It turns out that humans are poor monitors of automated systems. The FAA notes a tragic 1999 accident in Columbia involving two pilots of a multiengine aircraft that programmed its flight management system to fly into the face of the Andes Mountains. Paper charts showing the correct route were available in the cockpit.

The glass-cockpit marvels found in many aircraft also can result in complacency, as well as deterioration of piloting skills. Problems occur when such systems are used to make up for lack of skill and knowledge. —AKM