According to the model popularized by

Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross

in her seminal 1969 book On Death & Dying, there are five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. This is apparently what

Champion Aerospace LLC

has been going through over the past six years with respect to the widely reported problems with the suppression resistors in its Champion-brand aviation spark plugs. I last discussed this issue in my August 2014 blog post

Life on the Trailing Edge.

According to the model popularized by

Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross

in her seminal 1969 book On Death & Dying, there are five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. This is apparently what

Champion Aerospace LLC

has been going through over the past six years with respect to the widely reported problems with the suppression resistors in its Champion-brand aviation spark plugs. I last discussed this issue in my August 2014 blog post

Life on the Trailing Edge.

I first became aware of the Champion spark plug resistor problem in 2010, although there’s evidence that it dates back to 2008. We were seeing numerous cases of Champion spark plugs that were causing bad mag drops, rough running and hard starting even though they looked fine and their electrodes weren’t worn anywhere near the retirement threshold. The thing these spark plugs had in common were that they were all Champion-brand plugs and they all measured very high resistance or even open-circuit when tested with an ohmmeter.

We also saw a number of cases where high-resistance Champion plugs caused serious internal arc-over damage to Slick magnetos (mostly in Cirrus SR20s). If the damaged mag was replaced without replacing the spark plug, the new mag would be damaged in short order. The cause-and-effect relationship was pretty obvious.

In researching this issue, I looked at the magneto troubleshooting guide on the Aircraft Magneto Service website, maintained by mag guru Cliff Orcutt who knows more about aircraft ignition systems than just about anyone I know. Cliff owns and operates my favorite mag specialty shop, and that’s where I send the mags on my own airplane every 500 hours for inspection and tune-up. In reading Cliff’s troubleshooting guide, I came across the following pearls of wisdom:

|

We started asking the maintenance shops we hired to maintain our clients’ aircraft to ohm out the plugs at each 50-hour spark plug maintenance cycle. The number of plugs that measured over 5,000 ohms was eye-opening. Many plugs measured tens or hundreds of thousand ohms, and it wasn’t unusual to find plugs that measured in the megohm range or even totally open-circuit. Here, for example, is a set of 12 Champion plugs removed for cleaning and gapping from a Cirrus SR22 by a shop in South Florida:

Notice that only two of these 12 plugs measured less than 5K ohms, and one of those had to be rejected because its nose core insulator was cracked (a separate issue affecting only Champion fine-wire spark plugs, and unrelated to the resistor issue that affected all Champion plugs).

Why spark plugs have resistors

Early aviation spark plugs didn’t contain resistors. They didn’t last long, either. The reason was that each time the plug fired, a significant quantity of metal was eroded from the electrodes. Magnetos fire alternate spark lugs with alternate polarities, so half of the plugs suffered accelerated erosion of their center electrodes, and the other half suffered erosion of the ground electrodes. Eventually, the ground electrodes became so thin or the center electrode became so elliptical that the plug had to be retired from service.

Spark plug manufacturers found that they could extend the useful life of their plugs by adding an internal resistor to limit the current of the spark that jumps across the electrodes. The higher the resistance, the lower the current. And the lower the current, the less metal eroded from the electrodes and the longer the plug would last before the electrodes got so worn that the plug had to be retired.

Adding a resistor to the plug also raised the minimum firing voltage for a given electrode gap. The result is a hotter, more well-defined spark that improves ignition consistency and reduces cycle-to-cycle variation.

The value of the resistor was fairly critical. If the resistance was too high, the plug would fire weakly, resulting in engine roughness, hard starting, excessive mag drops, and (if the resistance was high enough) arc-over damage to the magneto and/or harness. If the resistance was too low, the plug electrodes would erode at an excessive rate and its useful life would be short. Experimentation showed that a resistance between 1K and 4K ohms turned out to be a good compromise between ignition performance and electrode longevity. Brand new Champion-brand aviation spark plugs typically measure around 1,200 ohms fresh out of the box. New Tempest-brand plugs typically measure about 2,500 ohms. Both of these represent good resistance values right in the sweet spot.

Denial

As word of these erratic and wildly out-of-spec resistance values began reaching aircraft owners and mechanics (primarily via the Internet), Champion went on the defensive. At numerous aviation events and IA renewal seminars, Champion reps dismissed the significance of resistance measurements. They explained that the silicon carbide resistor in Champion-brand plugs is made to show the proper resistance whenever a high-voltage pulse is present, and can’t necessarily be measured properly with an ohmmeter. Further, they stated that the proper way to test a spark plug is on a spark plug testing machine (so-called “bomb tester”), and claimed that if a plug functions well during a bomb test, it should function well in the airplane.

Of course, this “company line” from Champion didn’t agree with our experience. We’d seen numerous instances of high-resistance Champion plugs that tested fine on the bomb tester but functioned erratically in service. Nor did it agree with the Mil Spec for aviation spark plugs (MIL-S-7886B) which states clearly:

4.7.2 Resistor. Each spark plug shall be checked for stability of internal resistance and contact by measurement of the center wire resistance by the use of a low voltage ohmmeter (8 volts or less). Center wire resistance values of any resistor type spark plug shall be as specified in the manufacturer’s drawings or specifications.

One enterprising Cessna 421 owner named Max Nerheim performed high-voltage testing of Champion spark plugs, and found that plugs that measure high-resistance or open-circuit with a conventional ohmmeter also had excessive voltage drop when fired with high voltage, and required a higher minimum voltage to produce any spark. Max Nerheim wasn’t just an aircraft owner, mind you, he was also Vice President of Research for TASER International, Inc. and was exceptionally qualified to perform high-voltage testing of Champion spark plugs. Nerheim’s findings flatly contradicted Champion’s company line, and agreed with what we were seeing in the field. Nerheim also disassembled the resistor assemblies of a number of high-resistance Champion plugs and found that the internal resistor “slugs” were failing.

Anger

The spit really hit the fan when Champion’s primary competitor in the aviation spark plug space, Aero Accessories, Inc., launched a marketing campaign to promote sales of its Tempest-brand aviation spark plugs by highlighting the resistance issue. (Aero Accessories acquired the Autolite line of aviation spark plugs from

Unison Industries in 2010, an re-branded them under its Tempest brand.) In February 2013, they issued a Tempest Tech Tip titled “The Right Way to Check Spark Plug Resistors,” started selling a fancy spark plug resistance tester, and launched a big “What’s Your Resistance”

advertising campaign in the general aviation print media.

The spit really hit the fan when Champion’s primary competitor in the aviation spark plug space, Aero Accessories, Inc., launched a marketing campaign to promote sales of its Tempest-brand aviation spark plugs by highlighting the resistance issue. (Aero Accessories acquired the Autolite line of aviation spark plugs from

Unison Industries in 2010, an re-branded them under its Tempest brand.) In February 2013, they issued a Tempest Tech Tip titled “The Right Way to Check Spark Plug Resistors,” started selling a fancy spark plug resistance tester, and launched a big “What’s Your Resistance”

advertising campaign in the general aviation print media.

Predictably, this provoked a rather hostile response from Champion. Their field reps ratcheted up their public relations campaign claiming that the ohmeter check was meaningless, and insisting that Champion spark plugs didn’t have a resistance problem that affected the performance of their plugs.

Bargaining

In the face of both overwhelming technical evidence from the field that their spark plugs had a resistor problem, and a virtual blitzkrieg from their principal competitor that was starting to erode their dominant market share, Champion began having some self-doubts. Max Nerheim discussed his high-voltage test findings with Kevin Gallagher, Manger of Piston and Airframe at Champion Aerospace, and Gallagher acknowledged that Champion was looking into the issue with the resistor increasing in impedance, but did not have it resolved yet. Meanwhile, the Champion field reps continued to insist to anyone who would listen that claims of resistor problems in Champion spark plugs were false and that the ohmmeter test was meaningless.

Finally…Acceptance

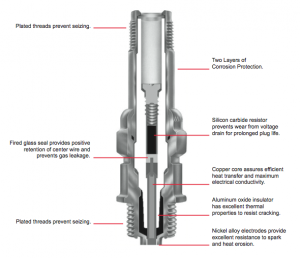

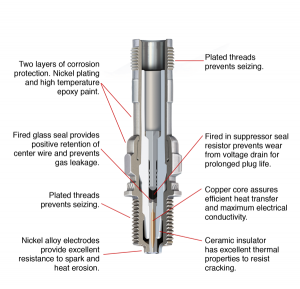

Sometime in late 2014, it appears that Champion very quietly changed the internal design of their spark plugs to use a sealed, fired-in resistor element that appears to be quite similar to the design of the Tempest/Autolite plug. They didn’t change any part numbers. So far as I have been able to tell, they didn’t even issue a press release. The Champion Aerospace website makes no mention of any recent design changes or product improvements. But the cutaway diagram of the Champion spark plug now on the website shows the new fired-in resistor. Here are the old and new cutaway diagrams. Compare them and you’l clearly see the difference.

|

|

I checked with a number of A&P mechanics and they verified that the latest Champion spark plugs they ordered do indeed have the new design. It’s easy to tell whether a given Champion spark plug is of the old or new variety. Simply look at the metal contact located at the bottom of the “cigarette well” on the harness end of the plug. The older-design plugs have a straight screwdriver slot machined into the metal contact, while the newer-design plugs do not.

As I write this, it’s still too early to tell whether Champion’s quiet resistor redesign will cure the drifting resistance problem, but my best guess is that it will. If I’m right, this is very good news indeed for users of Champion aviation spark plugs. I applaud Champion Aerospace for improving its product.

Still, I can’t help but wonder why it took six years for the company to work through its grief from denial to acceptance. I suppose grief is a very personal thing, and everyone deals with it differently.