A botched approach in a Cirrus SR22

Unstabilized approaches, regardless of aircraft size, are problematic. Positive transfer of control also is essential if that becomes necessary. A short Labor Day vacation trip for a student pilot, his CFI, and the students pilot’s wife turned tragic with a botched approach, but the causal factors may go well beyond the ones stated in the accident report. Probable cause in landing accidents usually is easy to ascertain, but the links in the accident chain are more subtle.

The flight

On September 1, 2012, a Cirrus SR22 departed Tweed-New Haven Airport in Connecticut on a VFR flight to nontowered Falmouth Airpark in Massachusetts. Just before 11 a.m. Eastern daylight time, the Cirrus entered the pattern at Falmouth. According to the student, they overflew the airport at 3,000 feet and descended to join the right downwind for Runway 7. The weather—reported from an airport four miles away—included a few clouds at 1,600 feet, visibility 10 statute miles, and wind from 066 degrees at 15 knots, gusting to 18 knots. Witnesses described the final approach over trees as “unstable, with rocking wings,” and one witness speculated the landing would be aborted.

Another witness wrote, “Subject aircraft was on a short final when he came in over the trees. He was low and slow. He got into a high sink rate and he went to full power and pulled the nose up abruptly, about 30 to 40 degrees nose up, and the airplane veered to the left and went into the trees and exploded on impact.”

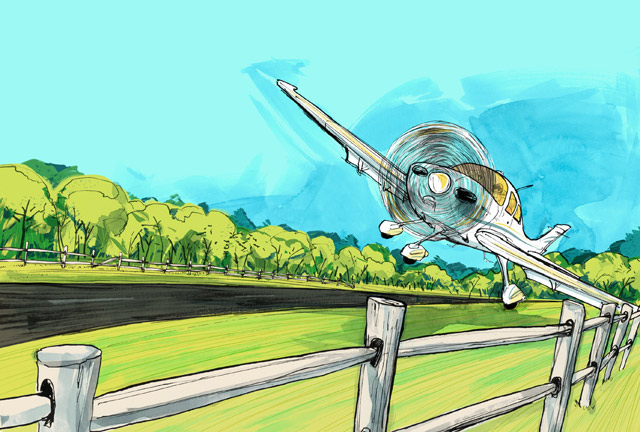

According to the NTSB report, “Exact recollections differed, but in general, witnesses recalled that as the airplane neared the runway, the airplane’s rate of descent increased, and there were some additions and reductions in power. The airplane started veering to the left, there was an addition of power, and the left wing almost hit the ground. The airplane then touched down in the grass to the left of the runway, went through the last section of a wooden fence, entered some woods, and burst into flames.”

The accident site had skid marks in the grass to the left of the runway where the left main landing gear touched down first. The marks began about 80 feet left of the runway, 300 feet from the approach end, on a 030 degree bearing into the woods. Flaps were measured at 50 degrees down. The wife, seated in the back, pulled her husband from the wreckage. A fire ensued and the CFI was killed. Both the student and his wife had serious injuries.

Recollections

The student pilot thought he was flying the airplane but recalled the CFI’s hands and feet on the controls, which he said happened often. He remembered clearing the trees at the approach end of Runway 7 when the CFI said they were “low and slow.” The NTSB report noted, “The student pilot did not remember much there-after other than than being ‘jounced around a bit.’ He did not remember ‘seeking’ the runway or touching down on or near the runway. He did not know if the CFI took control of the airplane, or if he continued to fly it, nor did he recall the CFI saying anything else to him other than they were low and slow. The next thing the student pilot remembered was the airplane hitting trees, breaking up, and coming to rest.

“In response to additional questions posed through his attorney, and after his release from the hospital, the student pilot recalled that the CFI had not [my emphasis] said that they were low and slow. Instead, the CFI had pointed to the airspeed indicator, ‘to indicate a slower than desired landing approach speed. He did not verbalize any words; he just pointed at the electronic display, which I understood to mean that he wanted me to note our speed, which was 69 knots, a slightly low speed.’ The wife also believed that her husband was flying the airplane, with the CFI providing instruction. She did not know if the CFI had his hands on any of the airplane’s controls at any point that day, but in the past had seen him do so.”

The CFI

The 24-year-old CFI held a commercial pilot certificate with single-engine, multiengine, and instrument ratings. He also held flight instructor certificates for single-engine, multiengine, and instrument airplane. Cirrus training was completed on September 29, 2011. His logbook listed 1,519 total flight hours, with 1,407 hours of single-engine flight time, and 1,002 hours of instruction given. The accident report did not include Cirrus SR22 flight time. The NTSB questioned the CFI’s fiancée about his activities before the accident concerning fatigue or stress, but nothing significant was noted.

Student pilot

The student pilot, age 55, reported 117 hours of flight time at the time of the accident, about 100 of which were in the SR22. His logbook was destroyed in the accident. He began flight training and bought a used SR22 shortly afterward.

The NTSB was curious why the pilot, with so much flight time, had not taken his private pilot flight test. His attorney responded, “He was not in a rush to obtain his private pilot certificate and believed that the additional time and instruction would only make him a better, safer pilot.” The pilot had not yet completed night flight or solo cross-country tasks.

The pilot and his wife used the aircraft for transportation and hired the CFI to fly with them while providing instruction.

The aircraft

The pilot purchased the 2008 Cirrus SR22 in April 2012. Total flight time was about 965 hours. No preimpact malfunctions were noted and no recorded data could be retrieved because of fire damage.

The airport

Falmouth Airpark has a single runway, 7/25, which is 2,298 feet long and 40 feet wide. The AOPA Air Safety Institute’s accident database recorded several landing accidents involving wind or short-field mishaps. AOPA’s Airport Directory reported obstacles for Runway 7 as, “Trees, 60 feet left of center, 33 feet high, 300 feet from end, 3.1 clearance slope.”

NTSB probable cause

The NTSB said the probable cause of the accident was, “The flight instructor’s inadequate remedial action. Contributing to the accident was the student pilot’s poor control of the airplane during the approach.”

Additional recollections

Five of the last seven of the CFI’s students had not passed their practical tests on the first attempt, but not because of pattern work or landings. The former students were complimentary of the instructor. He was described as “thorough, meticulous, and encouraging.”

The NTSB report said, “Only one noted that he rode the controls occasionally. Because the student pilot indicated that the CFI would be on the controls with him at times, the question of riding the controls was asked of the other five student pilots. Three said he did not ride the controls, one said that he would be on the rudders, and one, who was only with the CFI before her solo, said he did. All but one of the student pilots flew with the CFI in a conventional, yoke-configured airplane.”

On the morning of the accident, another flight instructor spoke with the CFI while walking out to the accident airplane. The NTSB report said, “The CFI seemed upset and for the first time ever, made disparaging remarks about the president of the flight school. The other CFI did not ask about what brought about the remarks. The student pilot recalled they were delayed about an hour waiting for the CFI. He appeared ‘normal but slightly distracted,’ but said something like, ‘ready to have some fun?’ During the flight, the CFI ‘seemed to be his normal self but somewhat casual.’”

Commentary

It’s clear as to what happened, but the why is more speculative. Many factors could have contributed, or it simply could have been a botched landing and go-around.

Falmouth Airpark can be challenging, especially in gusty conditions. Short runways surrounded by trees often have shifting winds that make approaches complex. There is not much margin for a heavily loaded SR22. The recommended short-field approach speed is 77 knots, slightly higher if it is turbulent. The student apparently was concerned about landing long, as noted by his comment that the aircraft was at 69 knots on final.

Based on the ambient conditions, the pilot’s operating handbook estimated a no-wind landing distance of about 2,375 feet. A Cirrus Owners and Pilots Association website discussion regarding minimum field lengths had the more conservative pilots suggesting a greater margin than may have existed for the accident landing.

FAR Part 23, the certification rules that govern Cirrus, requires that landing distance must reflect crossing the end of the runway at 50 feet, on speed, and with braking that will result in no undue wear on brakes or tires. ASI recommends the 50/50 solution, which is to add 50 percent to the 50-foot obstacle distance. In this case, that would be about 3,600 feet. In the hands of an experienced pilot, flown properly, the aircraft can be landed in less, but the margins are decreased; it all has to work.

The possible argument with the flight school president may have been a distraction for the CFI, but that is speculative.

Clearly, there was lack of supervision and proactive response before things got out of hand. It appears that much of the CFI’s experience was in lower-powered and more lightly wing loaded aircraft, so that should be considered. The situation could have been resolved by a timely and properly executed go-around.

Basic airmanship is critical, especially when big engines and relatively short fuselages are involved. For aircraft such as the Cirrus, there will be large left-turning tendencies, and in a go-around power must be applied smoothly along with sufficient right rudder. In any aircraft, instructors must clearly take command and say they are doing so before control is in jeopardy. It all seems so clear in retrospect.

Bruce Landsberg is the former president of the AOPA Foundation and is now a senior safety advisor for the AOPA Air Safety Institute.

Illustration by Brett Affrunti

Summary

> Student pilot, CFI, and passenger fly into short runway on a windy day.

> Witnesses see the aircraft on an unstabilized approach.

> Power is applied after a hard touchdown and aircraft drifts left into trees.