At age 91, Max “Pete” Patrisek is still high on the Martin B–26 Marauder. In November 1944, he was at the controls over Italy when his twin-engine bomber was hit just after bomb release. A German 88-mm flak round ripped upward through the aft fuselage and exploded, the blast killing his tail gunner and mangling the airplane’s rudder and elevators.

Patrisek worked the trim tabs and jockeyed throttles to level the stricken airplane and turn toward safety. Some 90 nerve-racking minutes later, he and his crew managed to make an RAF runway on Italy’s east coast. The Marauder “brought us back all shot up, with half the controls out. It was as rugged and reliable as the B–17,” Patrisek said.

Patrisek is right. In the European and Mediterranean theaters during World War II, Marauders posted 129,943 operational sorties and dropped 169,382 tons of bombs while losing less than half of one percent of the attacking force—a loss rate unmatched by any Allied aircraft. Behind the B–26’s record were well-trained, experienced crews, well-versed in both the virtues and faults of Martin’s fast, powerful machine.

B–26 basics

The B–26 emerged from a 1939 Army Air Corps competition for a new, twin-engine medium bomber. Martin designer Peyton Magruder’s sleek, torpedo-shaped entry won top marks for range, speed, and payload, beating out North American’s B–25. The Marauder featured an all-Plexiglas nose, streamlined fuselage, high-speed airfoil, a B–17-sized bomb bay, an electric dorsal gun turret, and a pair of 2,000-horsepower Pratt and Whitney R-2800 radials driving four-blade Curtiss-Electric propellers. With war already raging in Europe and China, the Army skipped the prototype stage and ordered 1,131 Marauders before the first one flew in November 1940.

Its stubby, shoulder-mounted wings were built for speed, but the Air Corps diverted the more powerful, turbo-supercharged R-2800 engines to fighter production, dropping the Marauder’s top speed to 285 mph. Heavier armament, extra fuel, and combat equipment slowed the aircraft further. B–26s typically cruised at 180 mph and bombed at 220 mph.

Seven airmen crewed each B–26: two pilots and a bombardier, navigator, engineer/top gunner, radio operator/waist gunner, and tail gunner. The Marauder bristled with as many as 11 .50-caliber machine guns. Its forward bomb bay, a deliberate copy of the B–17’s, could carry eight 500-pounders or four 1,000-pound bombs.

A hot ticket

The aircraft’s clipped, 65-foot wingspan and 37,000-pound gross weight gave it a high wing loading—and the associated high stall speeds. These characteristics led to deadly consequences after Pearl Harbor when new Marauders met new pilots, fresh from the nation’s burgeoning flight schools.

“A lot of the young pilots back then had only 230 hours and went into the left seat straight out of training,” said Ronnie Gardner, who flew the Commemorative Air Force (CAF) B–26 Carolyn before it was lost in a fatal 1995 crash. “Both students and instructors were inexperienced—they were between a rock and a hard place. The B–26 has such a high VMC [minimum single-engine control airspeed], they didn’t have the experience to handle an engine loss at high power settings.”

Mechanical failures, high takeoff and approach speeds, and unforgiving single-engine handling characteristics led to a rash of accidents among student crews. The airplane was soon labeled “Widowmaker,” and wags at Florida’s MacDill Field joked grimly that Marauder crashes there put “One a day in Tampa Bay.”

Even after Pearl Harbor, some in the Army Air Forces and in Congress were calling for an end to Marauder production, but Henry “Hap” Arnold, who would become General of the Army, needed every bomber he could get his hands on. Marauder crews fought at Midway, bombed the Japanese base at Rabaul from New Guinea, and by late 1942 were taking on Rommel’s forces in North Africa. Arnold ordered Gen. Jimmy Doolittle, the famed Tokyo raider, to get to the bottom of the B–26’s problems.

He and his aide, Maj. Vincent “Squeek” Burnett, undertook an extensive tour of stateside B–26 training bases, showing students and their instructors what the Marauder could do. Doolittle would famously release brakes, feather a propeller just past VMC, take off single-engine, turn steeply into the dead engine, and roll out to a safe landing. “Although the Marauder remained a dangerous airplane in the hands of the unskilled, it had an excellent record later when properly trained pilots took it into combat,” Doolittle wrote.

Matching Doolittle, Burnett in his demos would throw his combat-loaded B–26 around the control tower with a feathered prop, turning always into the dead engine. He’d close the deal with a single-engine aileron roll over the field, then swing around to land in front of the amazed trainees. Test pilots from Martin and the Army’s Wright Field, along with returning B–26 combat vets, soon schooled the Marauder instructors in the critical skills their students needed to survive.

For its part, Martin lengthened the B–26’s wing to 71 feet, increased vertical stabilizer height by 20 inches, and added slotted flaps and a lengthened nosewheel strut. These improvements and better training soon buried the B–26’s bad reputation; its 1943 accident rate dropped 60 percent from the previous year. Marauder crews got on with the business of winning the war.

Flying the Marauder

Sherman Best, now 94, who in 1944 skippered a B–26 through three missions on D-Day, recalls that the machine “was a good airplane to fly. It had quick control response, but it required your constant attention.” There was no autopilot.

Crews appreciated the Marauder’s ruggedness. “The B–26 was a sturdy aircraft. It was very well built, and had good armor protection. It could take a beating,” Best said. With the 88s in mind, crews wore apron-like flak suits and GI-style steel helmets.

Best learned the idiosyncrasies of the B–26 in late 1943 from his first aircraft commander, who knew the airplane inside and out. At takeoff power, the book says you’d lift the nosewheel off at 80 to 90 mph and let the aircraft fly off the runway. In reality, says Best, takeoff speed “was what you had at the end of the runway. Hold your breath ‘til you’re off!” Raising gear and flaps, pilots hawked the airspeed indicator for the safe VMC of 160 mph.

Once cleaned up, the B–26 was an honest airplane. “It was responsive and reasonably maneuverable,” says Patrisek. “It didn’t handle as nimbly as a fighter, but it was good for a bomber.”

Best says the B–26 “had quick control response, and was easy to fly in formation.” He typically flew 10 to 20 feet off his leader’s wing tip. “But you needed a little strength to fly formation well. At the end of four hours in the air, you were pretty tired.”

Sweating single-engine

Aside from deadly run-ins with flak and fighters, the B–26 pilot’s biggest challenge was handling the loss of an engine during takeoff or approach. Laden with bombs, fuel, and ammo, both radials revved to full power, the Marauder was vulnerable. If an engine died or a propeller governor failed to flat pitch just after lifting off, well below VMC, the aircraft would immediately roll—with fatal consequences.

A B–26 pilot manual puts it starkly: “The B–26 in a climbing attitude with full power on one engine and no power on the other will go over on its back in a flash at airspeeds of 135 and below…. Your only chance is to keep the airplane under control by reducing power [on] the good engine and landing straight ahead. If your hand is not on the throttle, however, the airplane will roll before you can get it there in time to reduce power.”

Kermit Weeks, whose Fantasy of Flight collection in Florida includes a 1941 B–26, flew the airplane—salvaged from the site of a crash landing in Canada—regularly. “If you missed putting the propeller control back in Auto after your pretakeoff checks, you’d take off in flat pitch and go straight into the water. It was a real gotcha”—one that claimed the lives of many inexperienced wartime crews.

The key to survival on takeoff was raising the gear, staying low, and accelerating to single-engine VMC. In a fully loaded Marauder, that’s 163 mph.

Losing an engine at cruise speed was much easier to handle. Maintain control with immediate rudder to control yaw. Feather the dead engine’s propeller, making sure you feather the correct prop. Trim out the rudder forces. The manual advised getting rid of bombs and excess fuel, and maintaining 160 mph or better in a gradual descent. To get the Marauder safely on the ground, make turns into the good engine and keep the approach speed above 140 mph, using flaps as necessary. “The airplane will not hold altitude on one engine with gear down,” the manual warned.

Gardner, who flew the CAF’s B–26, is just as blunt about a single-engine approach in the Marauder: “If you try to go around, it’ll roll over on its back and kill you. You have to respect its VMC and know what it’ll do and won’t do, single-engine. Keep the gear and flaps up until you know you’ve made the field.”

Survivors

Today, testing your skills in a B–26—as young Army pilots did 70 years ago—is a tough proposition. The Fantasy of Flight Marauder last flew in 2004, and Weeks says it needs at least one new engine and a rigorous inspection before it could again be airworthy.

The MAPS Air Museum at Akron-Canton Airport in Ohio has a B–26, salvaged from the British Columbia wilderness. Crew chief Dave Pawksi says the restoration is about 95 percent complete. MAPS volunteers recently installed the bombardier’s Plexiglas nose; engine cowlings are next. The museum has no plans to fly its impressively rebuilt Marauder, Charlys Jewel.

The National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, and the Utah Beach D-Day Museum in Normandy, France, exhibit fully restored, late-model B–26G Marauders. Neither Shootin’ In nor Dinah Might is airworthy.

The Pima Air and Space Museum in Tucson owns the remaining sections of the third Canada-salvaged B–26. Its Marauder eventually will be exhibited in the museum’s planned Pacific Theater hangar. The Hill Aerospace Museum in Utah also has some major B–26 components.

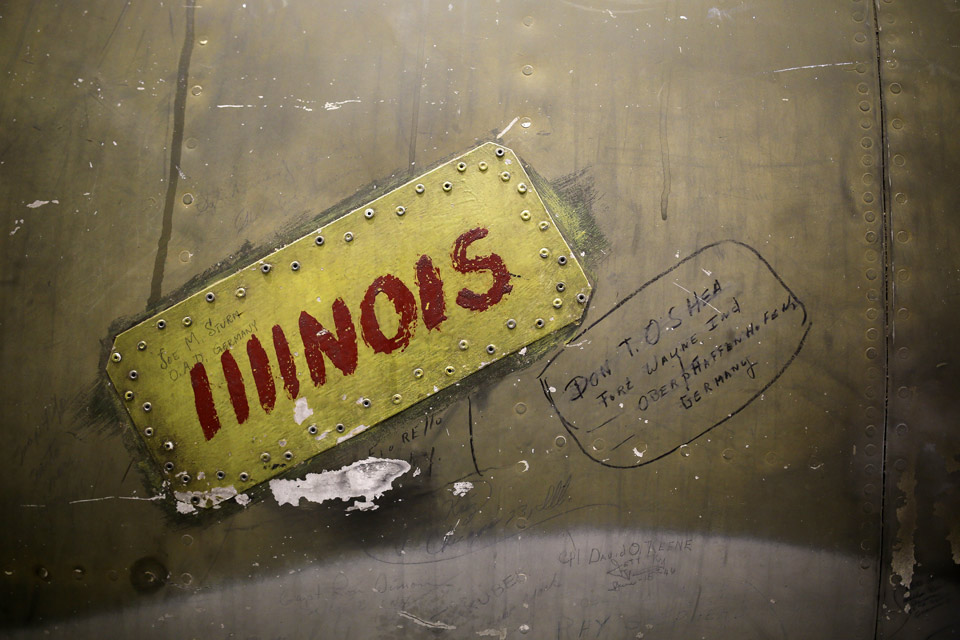

Finally, there is Flak-Bait, the B–26B-25-MA that rolled out of Martin’s Plant 2 in Middle River, Maryland, in April 1943. Flak-Bait—flown often by Sherman Best’s crew—completed 207 combat missions in Europe, more than any other American aircraft. Its flak-battered nose section was a highlight of the National Air and Space Museum’s World War II gallery in downtown Washington, D.C. The rest of Flak-Bait survived nearly 70 years of crated storage before the museum began its conservation and reassembly last August. Pat Robinson, one of the restoration specialists assigned to the Marauder full-time, says the aircraft is packed with history. “We’ve found handfuls of chaff [radar-defeating foil strips], tools, cigarette butts, .50-caliber shell casings, and live rounds. Pieces of German flak are still coming out of the airplane. It’s an absolute time capsule.” You can view Flak-Bait undergoing patient reassembly in the Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar at the museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center at Washington Dulles International Airport, in Chantilly, Virginia.

The surviving Marauders represent the thousands of Martin workers in Baltimore and Omaha who built the airplanes, as well as the veterans who mastered the Marauder through the darkest days of 1942 and then went on to speed the defeat of Nazi Germany.

Patrisek came down from Pennsylvania to visit Flak-Bait in April, taking a long look at the airplane he flew and loved. “I never heard any bitching or complaints about it from the pilots,” he said. “It was an outstanding airplane, and it took good guys to fly it.”

Tom Jones flew B–52s in the Air Force before flying four times on the space shuttle as a NASA astronaut. Co-author of the World War II true story of P–47 Thunderbolt combat—Hell Hawks!—he is still hoping to check out in a B–26. Read more online.