Weather

Storm chasers

One of the most important things pilots learn about thunderstorms is not to fly into them. In fact, don’t fly even within 10 miles of any thunderstorm, and stay 20 miles away from severe thunderstorms.

Nevertheless, our basic scientific understanding of thunderstorms owes a great deal to pilots who deliberately flew through thunderstorms in 1946 and 1947.

The story begins with the great expansion of U.S. air power before and during World War II, the invention and growth of technology such as radar, and the hundreds of meteorologists and weather technicians the U.S. Army and Navy trained and used. When the war ended, some of these meteorologists and weather technicians—and a few pilots—undertook the research that led to unprecedented advances in understanding and forecasting all types of weather.

Taking on thunderstorms

Airline pilots had recognized thunderstorms as being especially dangerous since the 1930s, when they mastered the then-new technologies and techniques of instrument flying. In 1938, for instance, Assen Jordanoff wrote in Through the Overcast: The Weather and the Art of Instrument Flying that airline pilots “religiously avoided” thunderstorms because their severe turbulence “not only causes considerable personal discomfort, but places a severe strain upon the aircraft itself.”

Pilots tried to avoid thunderstorms, as they still do, but recognized that knowing more about thunderstorms would help with avoidance—and to cope with those they couldn’t avoid.

Flying into thunderstorms for science

Soon after World War II ended in September 1945, the Civil Aeronautics Board (a forerunner of today’s FAA), the military, and university meteorology professors created the world’s first large research project aimed at learning more about a meteorological phenomenon. This “Thunderstorm Project” deliberately sent airplanes into thunderstorms to learn what goes on inside and around them.

The U.S. Weather Bureau (now the National Weather Service) ran the project with major help from the Army Air Forces (which became the U.S. Air Force in September 1947) and the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, which became part of NASA when it was formed in 1958.

The Thunderstorm Project began during the summer of 1946 south of Orlando, Florida, using 10 U.S. Army Air Forces Northrop P–61 Black Widow airplanes. In 1946 each crew included a pilot and radar operator. When the experiment moved to Ohio in 1947 a weather observer was added.

The researchers hoped to discover more about how thunderstorms work in addition to learning specific things that would help pilots avoid or better cope with then.

During the experiment the P-61s flew into 76 thunderstorms, often back and forth through storms, for a total of 1,362 storm penetrations.

The airplanes measured turbulence, updrafts and downdrafts, and electrical fields, as well as temperature and humidity. To record updrafts and downdrafts, the pilots allowed their airplanes to go up or down with the air currents instead of trying to hold fixed altitudes.

Radar and radio technologies developed in World War II allowed researchers to follow the airplanes’ movements, recording the data by taking photos of their radar scopes. None of the airplanes crashed, although lightning hit them 21 times and they often landed with dents from hailstone strikes.

Airplanes only part of the project

In addition to using the P-61s, the researchers set up 54 weather stations that automatically recorded such data as temperature, humidity, atmospheric pressure, and wind speed and direction in a 7-by-13-mile open area south of Orlando. The researchers also used weather radar and weather balloons, but their real innovation was to have the airplanes fly directly through thunderstorms to collect data.

In 1946 the project was based at Pinecastle Army Air Base south of Orlando, which is now Orlando International Airport. The following year, it operated from the Clinton County Army Airfield near Wilmington, Ohio, now Wilmington Air Park. As in Florida, they also set up a grid of land-based weather stations in Ohio.

Both locations gave the researchers military airports and other nearby facilities such as supply and repair depots. The Florida research area sees, on average, more thunderstorms each year than anywhere else in the United States. Going to Ohio for the second year ensured more opportunities to fly in thunderstorms associated with cold fronts and squall lines that are typical of Ohio’s inland, continental climate than in Florida’s subtropical climate.

Horace R. Byers, a University of Chicago meteorology professor who directed the project, and Roscoe R. Braham, the project’s senior analyst, reported on the project in a 287-page book the Weather Bureau published in 1949 titled The Thunderstorm.

How they did it

The basic research plan required that at least five airplanes fly through each thunderstorm at altitudes 5,000 feet apart, ranging from 5,000 to 25,000 feet above sea level. “An effort was made to perform these flights through the most vigorous thunderstorms,” Byers and Braham wrote. The P-61s flew a total of 70.3 hours inside thunderstorm clouds.

“No storm was to be avoided because it appeared too big. Storms were detected and followed, and the airplanes controlled and vectored, using a large ground radar located near the operations area. Continuous photography of the radar scopes provided information about the storm as well as locations of the planes.”

One finding should make any pilot think twice about flying into a thunderstorm: The airplanes flew into thunderstorm updrafts as fast as 58 mph and downdrafts as fast as 38 mph. At times such updrafts and downdrafts may be adjacent to each other, creating extreme turbulence to an aircraft flying through them.

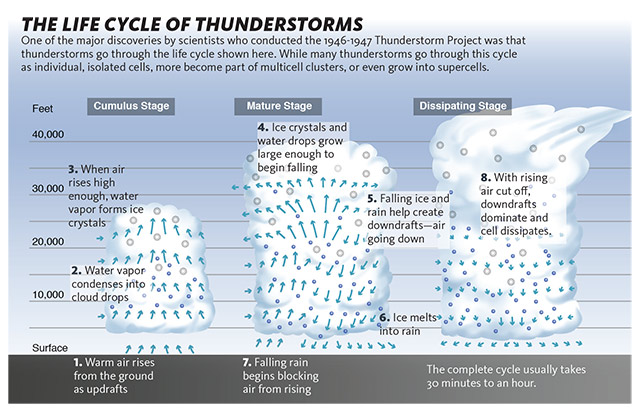

The Thunderstorm Project uncovered the fact that thunderstorms go through a three-stage life cycle. A graphic of the life cycle that first appeared in The Thunderstorm is re-created on page 45.

In addition to learning the basics of how thunderstorms grow and develop, the Thunderstorm Project helped lead to the development of on-board weather radars for airplanes. The Black Widows had been designed as night fighters that used radar to hunt and shoot down enemy airplanes, but their on-board radars worked well at spotting thunderstorms.