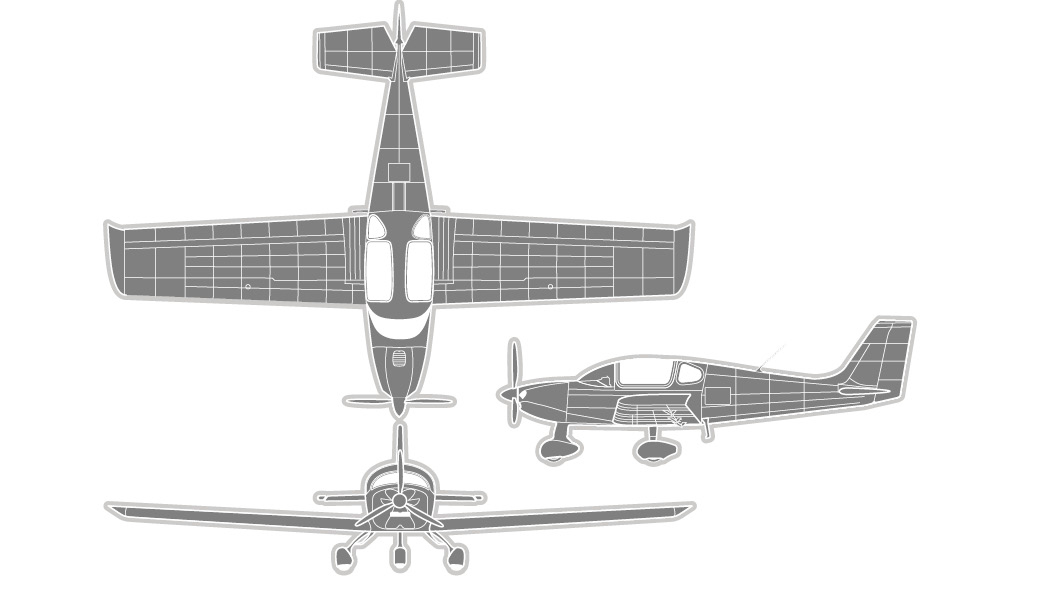

More from less: The Sling 4

Tons of performance from low horsepower

An Airmaster electrically controlled constant-speed propeller hub from New Zealand; Whirlwind propeller blades from El Cajon, California; and a Rotax engine from Upper Austria help the 115-horsepower airplane turn in impressive numbers. “Without the constant-speed prop and turbocharger, it wouldn’t work,” said Matt Liknaitzky, president of The Airplane Factory USA in Torrance, California.

The Sling 4 can take more than 900 pounds of people and fuel nearly 800 nautical miles, and climb to altitude at 800 feet per minute—all with only a 115-horsepower Rotax 914 UL turbocharged engine.

That’s typical of new-technology general aviation airplanes: doing more with much, much less. The Sling 4 will get you wherever you need to go at 130.5 knots true airspeed at 85-percent power, and it can run at 85 percent all day (or night). Eighty-five percent is the highest continuous power setting, and that equals only 100 horsepower. The remaining 15 horses are allowed out of their stables for only five minutes during takeoff.

For U.S. buyers there is only one condition: You have to build it. In South Africa there is a special category that allows the factory to build it for you. Half of the 60 or so Sling 4s now flying were built at the factory. In the United States 10 kits have been sold so far, and they are the kind that take 900 to 1,200 hours of work—about two years. At the time this was written there were two prospects considering purchase of a quick-build, two-week kit that was introduced in the summer of 2015 and can be assembled in 600 hours.

The company has contracted with Synergy Air in Eugene, Oregon, to train builders in the classroom and then assist with the two-week ready-to-taxi construction. The company primarily serves Van’s RV kitplane owners. Just so you know, they’re not going to build it for you. Add on the two-week-build kit plus paint, and the total reaches $190,000 for a completed aircraft. Painting is not part of the two-week process.

By now you’ve done the math and discovered that 600 hours equals 25 days around the clock, not two weeks of work, but Synergy knows tricks that make it approximately a two-week job—and it pre-trains its customers in the classroom. It’s like walking into an operating room where special tools are laid out and the procedure is organized, owner Wally Anderson said.

He is enthusiastic about the airplane. “It’s well built, the representatives are enthusiastic, and there is good factory support,” said Anderson. At the time this was written he had 11 Van’s RV customers but no Sling customers. A new prospect for a Sling 4 quick-build kit had taken a training course at Synergy, but had not yet indicated he will buy the airplane.

Not a builder? It can save you money to become one.As a builder, you can do your own annual inspections and maintenance if you get a repairman certificate after a 30-minute quiz by the FAA. The Rotax engine prefers mogas, another savings in addition to the maintenance. Also, it’s just fun to fly.

The Sling 4 I evaluated was classified Experimental Exhibition because it was built by the factory, but the one you would probably prefer would be Experimental Amateur-Built—a much less restrictive category. Amateur-Built means you can use it for personal, not commercial use; train only yourself in it; and fly day, night, and in instrument conditions. The one I flew had been built at the factory in four days by 40 people in 2014, which explains the 4-4-40 on the tail: a Sling 4 in four days by 40 people.

My evaluation started out at Chino, California, but had to be completed the following day at Torrance, 30 miles to the west. After ground photos were taken at Chino, a loose fitting on the right brake dumped all the brake’s hydraulic fluid on the ramp near AIA Flight Training, and the flight was postponed. Since the nosewheel can be steered, factory representatives used it to counteract the left wheel’s braking force during the landing at Torrance with no problems, demonstrating the value of positive steering. A castering nosewheel would have made braking more difficult. I was told later that the fitting on the left hydraulic brake had also come loose.

Stalls conducted east of Zamperini Field resulted in a drop of the left wing—nothing dramatic. There were three people in the aircraft, one of them sitting in the left rear seat. For the test flight, Liknaitzky and I were joined in the back seat by Jordan Denitz, marketing director at the Torrance office—intentionally adding extra weight to see if the Rotax could handle it (a fourth person was not available). Even with the extra weight, the initial climb rate was 900 feet per minute, dropping to 600 feet per minute as I backed the throttle out of the 115-horsepower position. The speed test was the most impressive part of the test flight, recording 130.5 knots true airspeed at 85-percent power at 2,500 feet—the way an average pilot might operate the aircraft on a long trip.

For shorter trips the pilot might prefer a lower power setting to save fuel. Even at that speed, the fuel consumption was only 6.1 gallons of auto gas per hour.

Landings were enjoyable. Pilots from The Airplane Factory USA keep speeds early in the approach at 80 knots until short final, given that the nearby neighborhoods are packed close to the Torrance airport. The idea is to have enough energy to glide to the airport during the approach should the engine quit. Only on short final is the speed reduced to between 65 and 70 knots. The airplane glides close to the runway and floats a bit—providing plenty of time for the pilot to prepare for the flare, which happens slowly. I landed on the main gear with the nosewheel high in the air on the first try. Visibility was excellent in all phases of flight.

Exiting the airplane, I noticed the high cabin wall requires a big step, and makes stepping on the seat upon entry almost a requirement. That’s no problem with a dry, clean ramp but it could be a problem in snow or rain. It is possible to enter and sit down without stepping on the seat, but you need to keep your gym membership active—and actually go to the gym—to lower yourself into the seat. The aircraft is controlled with a stick that has microphone and electric trim buttons. The back seat cushion is Velcroed to the airplane and is easily removed for extra baggage room.

The main operating difference for pilots comes from the three-blade propeller’s electric pitch control. Auto is selected on one switch, and a second switch is set to the takeoff position or TO. After 1,000 feet or so the switch is moved to Climb; you set it to Cruise upon reaching altitude. For landing, it needs to be reset to TO. The propeller automatically maintains appropriate revolutions per minute for the selected phase of flight, or it can be set manually to any desired speed.

Another difference is the sight picture out the window. I was constantly climbing until I discovered the correct attitude in level flight was what appeared to me to be a nose-low position. Turbocharging is always active, but really kicks in during the final travel of the throttle. There is a detent at the 100-horsepower setting; a lever on the throttle must be lifted to push the power past the detent and up to 115 horsepower, which is limited to five minutes. Warning lights notify the pilot if that time limit is exceeded.

For $192,000 you can have the luxury version with nearly every option, including an MGL Avionics glass cockpit from a South African company that Liknaitzky also represents. You’ll get the Whirlwind propeller blades, the Airmaster system, dual 10-inch MGL touchscreens (with buttons for use in turbulence), an airframe parachute by Stratos ballistic parachutes in the Czech Republic, and a two-axis MGL roll-and-pitch autopilot. Or for an additional $5,290 you can opt for the Garmin GNC 255 navigation and communication radio that receives localizer and glideslope information, rather than the Garmin GTR 200 radio with two-place intercom (a PS Engineering PM1000 four-place intercom is standard as well).

The quick-build kit arrives with the wings and cockpit nearly complete (you are responsible for building the tail) and costs an extra $15,000. “Most build at home,” Liknaitzky said. “A lot of people would like to build but are not sure they have the time and qualifications. If you want to be absolutely certain you will complete it in two weeks, the turbo build is the way to go.”

A slow-build kit with “extras” (such as the radio) for the standard model costs $108,417, so the quick-build kit brings that up to $123,417. Paint and avionics make up the rest of the $190,000 to $192,000 total. As with most kitplanes, construction is aluminum but composites play a role. There is a multi-ply composite landing gear and composite wheel pants. The engine cowling, wing tips, tail fairing, and canopy also are composite.

Few Americans are familiar with The Airplane Factory and the Sling. To counter that, the South Africa company proves its mettle—and metal—by flying its aircraft around the world. Both the two-seat Sling offered years ago and now the four-seat model have made the trip.

The Sling 4 may be the answer for folks who believe two-seat Light Sport aircraft aren’t quite enough, but half-million-dollar four-seaters cost too much. And it’s fun to fly. Did I mention that already?

Email [email protected]