The Eagle Rises

Ideas from high-tech auto racing help bring back a seminal airplane

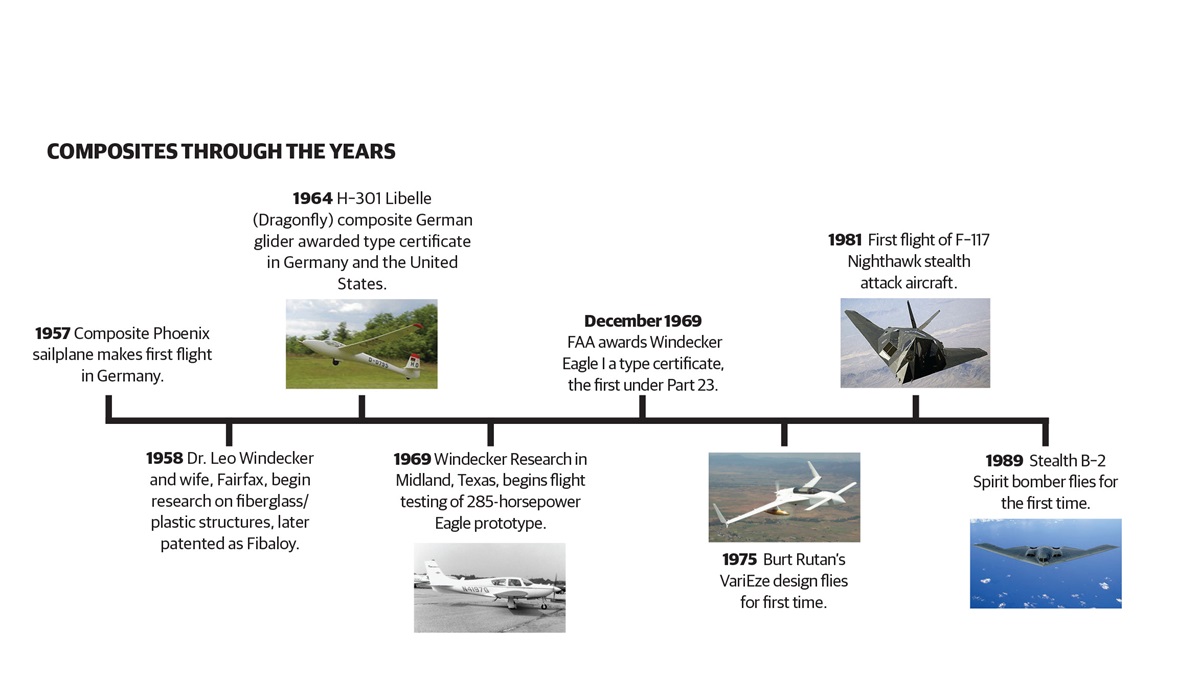

How fitting, then, to arrive at the aircraft’s test site in New Bern, North Carolina, in a snowstorm with Canadian-like temperatures of 13 degrees Fahrenheit the next morning, weather familiar to N4198G. The aircraft is still fast at 159 knots, its aerodynamic stall as gentle as the dental researcher had hoped. In 1969, the Eagle became the first powered composite aircraft to be certified by the FAA. Several accidental factors contributed to the Windecker airplane’s birth decades before fiberglass and carbon fiber airplanes became commonplace.

A flying enthusiast, Windecker wanted to do research; but the dentist’s growing family required that he accept an offer to open a practice in Lake Jackson, Texas—a town designed by Alden Dow of Dow Chemical in 1940 for Dow workers. His Dow patients told Windecker of a new lightweight glass-fiber material, and he was convinced that he could build an airplane from it with the company’s support. Dow today owns 17 of the 22 U.S. patents associated with Windecker’s companies.

When the Eagle first flew, it caused a sensation because it was made of “plastic.” Composite wasn’t in the lexicon at the time, and neither was stealth. The Eagle failed mainly because the company ran out of money needed for production. Mysteries remain about the “plastic airplane” that flew onto the covers of most aviation magazines in 1970 (including this one), thanks to its near-invisibility to radar—except for the engine and landing gear.

Did the Windecker Eagle contribute to today’s stealth technology? Maybe. Windecker made 30 or so stealthy laser-target-designator drones for the U.S. Department of Defense under contract with today’s Lockheed Martin, which gained access to the technology. So, in an indirect way, yes.

Radar returns were first tested with an Eagle mounted on Styrofoam pillars at Holloman Air Force Base, New Mexico, and more testing was done at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland. The U.S. Air Force later tested it at Eglin Air Force Base before the aircraft went black—or blacker. Windecker ended support for the blue-painted Air Force YE–5, as it was called, in 1976 when Texas oilmen pulled their financial support from the struggling company. The YE–5 had been made as stealthy as possible, per the contract.

Part of its history remains classified today. “I have not one ounce of information on what they did with the airplane or where they did it,” said Ted Windecker, Leo’s son, who is the chief technology officer of the current company. Who are “they”? Well, no one knows, but whatever happened occurred in the late 1970s and 1980s. The assumption is that the aircraft was operational overseas, perhaps used by the spy world. Windecker was told only that it did its thing “across the pond” and “saved lives.”

How does Ted Windecker feel today to see an Eagle fly again? “Gosh, it’s a thrill,” he said. “I’ve been talking about this for 10 years.”

Just as Windecker had to think outside the aluminum box when he first built the airplane, so did airplane and powerplant mechanic Mike Moore, who helped restore the P–38 Lightning Glacier Girl, and Don Atchison when the Eagle was restored. Atchison, who has military aviation logistics experience, is chief executive officer of Windecker Aircraft in Mooresville, North Carolina, known as “Race City.” It’s where Nascar and other race cars are built. A state-of-the-art wind tunnel is located across the street, and four more are within 10 miles. What’s missing from the complex is an airport. To fly, the restored Eagle had to be trucked 25 miles to Statesville, North Carolina.

The racing industry is represented by several of the nine-person team, led by three FAA-designated inspectors, who brought N4198G back from cryogenic suspension, its metal parts ruined by exposure in an open Canadian field. It took more than $1 million to restore the 1970-priced $49,500 airplane. “We forced ourselves to do some serious magic to get the gear back to optimal,” Atchison said. Among the team are Jim Jones of Tra-Co Racing Engines; dirt racer Jeff Smith, who is a virtuoso on a computer-aided drafting machine; and Tim Nye, who builds 900-horsepower winged outlaw cars that run in the World of Outlaws Spring Car series. In all, they made 500 to 700 parts from scratch, including the composite spinner, firewall, and composite rear bulkhead, not to mention the new composite engine cowling needed for the larger 310-horsepower engine. The cowling was checked for drag by aerodynamicist John Roncz, who is leading the next phase, a total new design.

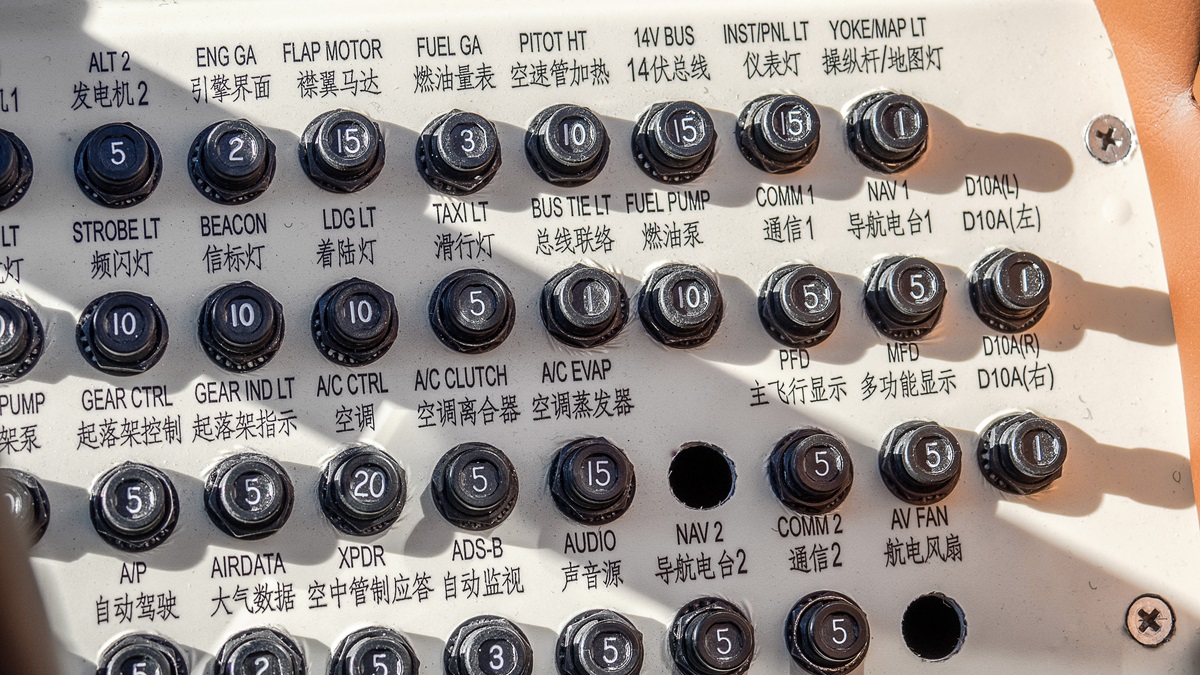

Atchison is from the motorcycle racing world. He runs Windecker Aircraft for Wei Hang of China, a real-estate mogul who plans to use the restored Eagle for marketing and government familiarization. Wei’s plan is to return the Eagle to production in China, although its configuration will not be exactly like the luxurious restoration. The production aircraft won’t have Garmin G3X touchscreen avionics, because that model is approved only for Experimental aircraft. It may have the 310-horsepower Continental IO-550 engine rather than the 285-horsepower Continental IO-520 engine listed on the Eagle type certificate—the first type certificate to be awarded under the FAA’s then-new Part 23 regulations. However, the Continental engine won’t be the option favored by most Chinese buyers because of the scarcity of 100LL avgas there. One Chinese pilot has a 100LL fuel truck follow him to his destination so that he can fly home, because there’s no 100LL where he is going. That’s why Wei is also an investor in EPS diesel engines and its Graflight V-8 that runs in the 320- to 420-horsepower range.

Despite the greater horsepower in the restored airplane, speeds were close to what Leo Windecker saw—183 miles per hour true airspeed during my flight at 65-percent power, versus 185 to 190 miles per hour at 75-percent power for the model in the 1960s and 1970s, Ted Windecker said. (Test pilot Len Fox noted the airspeed system had not been calibrated as yet.) The restored model is 250 pounds heavier than the original design; it has a heavy air conditioning unit in the rear, a leather interior, past repairs from belly landings, an autopilot, overhead lighting, shoulder harnesses and hardware, heavy-duty brakes, and two backup batteries. A modern propeller and Dynon backup instruments helped save weight, as did the Garmin panel. In all there are 300 deviations from the original type certificate on the restored model, because it is going to a country with an expectation that private aircraft will match luxury cars.

The stall I performed went safely, as Windecker had insisted more than 40 years ago—a little burbling and vibration straight ahead, followed by a gentle drop of the nose. That’s what you get from a rectangular wing, Ted Windecker said. The strake added to stop accelerated spins that crashed a prototype decades ago is still in place. With the strake, the aircraft came out of a spin by itself after three turns.

Roll rate was reasonably crisp, although it wouldn’t impress an aerobatic pilot. Test pilot Len Fox found a roll rate of 40 degrees per second at an indicated 150 mph, and 25 degrees per second at 100 mph. The elevator controls had a quarter-inch of play, as did the original design—you have to pull or push a quarter inch before the elevator moves up or down. Final approach is flown between 100 and 105 mph (about 90 knots).

As Hubie Tolson, who completed the aircraft’s 25-hour flight test requirement, noted, it was then a work in progress and had a brief squawk list of items to address. When the gear was lowered for landing, cold air came into the cockpit—a problem quickly solved later by relocating ducting tubes. Back-seat passengers need to exit first, before the front-seat passengers leave the wing, or the tail will tilt down to the ground. Those problems will not exist in the production airplane, Ted Windecker said. Other issues, such as the lack of a footwell in the back and the need for extra headroom up front, will only be cured by a new design, which Windecker announced in February.

Because the rear floor is close to the seat level, back-seat passengers get to study their knees intensely during flight. Five beefy wing spars run through the cabin and the main gear fold under the cabin.

The new design team is headed by the self-taught Roncz. He designed the rigid sail aboard the Stars and Stripes boat that successfully defended the America’s Cup in 1988. He also worked on Steve Fossett’s Virgin Atlantic GlobalFlyer, the Icon A5 amphibious Light Sport aircraft, and the Rutan Voyager around-the-world aircraft. Roncz also worked on aerodynamics for 17 airplanes for Burt Rutan—“that the public knows about.” In all there have been more than 50 designs that include his work.

The new certified design, to be called Tian Hu, could lead to a family of airplanes—the team had been challenged to keep an open mind, including turboprops and jets. It is an all-new design, Atchison said.

“You will not see a modern version of the plastic airplane that was on AOPA Pilot’s cover in 1970, but [I am] happy to report that you will definitely see a John Roncz-designed, advanced, high-performance, low-wing, propeller [driven], certified composite airplane in the near future.” The folks at Windecker Aircraft are not sitting idle in Mooresville watching soap operas now that one restoration is complete.

The mysteries of the Windecker Eagle that started decades ago continue.

Email [email protected]

Spec Sheet

Original Windecker Eagle

1970 Base price: $49,500

Specifications

Powerplant | 285 hp Continental IO-520-C

Propeller | 2-blade McCauley (no longer made)

Length | 28 ft 6 in

Height | 9 ft 6 in

Wingspan | 32 ft

Seats | 4

Empty weight | 2,150 lb

Max gross weight | 3,400 lb

Useful load | 1,250 lb

Payload w/full fuel | 770 lb

Fuel capacity, std | 84 gal, 80 usable (72 gal for restored airplane with bladders, 68 usable)

Baggage capacity | 120 lb

Performance

Takeoff distance, ground roll | 855 ft

Takeoff distance over 50-ft obstacle | 1,690 ft

Max demonstrated crosswind component | 18 kt (12 kt for restored airplane)

Rate of climb, sea level | 1,220 fpm

Cruise speed/endurance w/45-min rsv, std fuel 7,000 ft @ 75% power, best economy | 204 mph TAS

@ 65% power, best economy | 202 mph TAS

Service ceiling | 18,000 ft

Approach speed, flaps down | 130 mph IAS

Limiting and recommended airspeeds

VA (design maneuvering) | 136 mph IAS

VFE (max flap extended) | 130 mph IAS

VLO (max gear operating)

Extend | 150 mph IAS

Retract | 130 mph IAS

VNO (max structural cruising) | 190 mph TAS

VNE (never exceed) | 234 mph IAS

VS1 (stall, clean) | 71 mph IAS

VSO (stall, in landing configuration) | 66 mph IAS

Extra

The original Windecker at 65-percent power was faster than the restored model, despite the restored model’s more powerful engine—probably because of the weight increase from added luxury items.