How it works: Mixture control

Tossing an air-and-gas salad

How to get rid of the mixture control

Some airplanes have something called FADEC (full-authority digital engine control). Computers figure out proper mixture settings, leaving the pilot out of the loop. There’s no mixture control!

Sometimes, though, it is the same color as the rest of the levers (or knobs). Pilots who pull it while in flight learn an important lesson: Don’t do that.

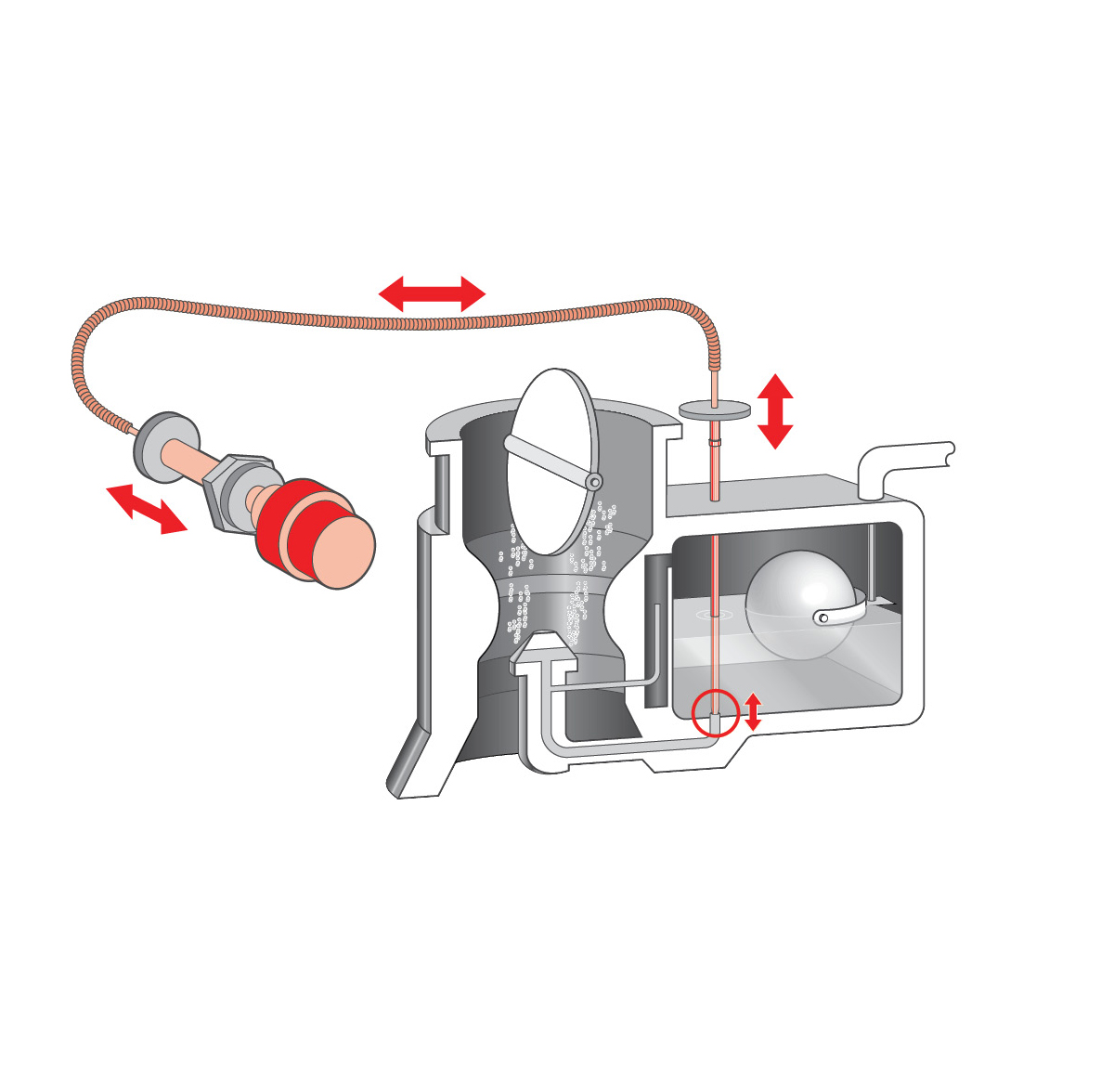

While it looks techy, actually the mixture control simply pulls on a cable that passes through the firewall out to the engine’s carburetor. There, it operates a needle that’s like a floodgate; it can change the amount of fuel allowed through at any throttle setting. Remember the little boy who put his finger in the dike and saved Holland? Put a finger into the dike and very little water leaks out. Remove it, and as much water as possible comes out. The mixture needle in the carburetor works like that.

Lower the needle into the fuel line going to the carburetor’s discharge nozzle, and it can lean the mixture for higher altitudes; retract the needle from the fuel line opening, and it can enrich the air/fuel mixture for operations at lower altitudes. At high power settings, the throttle can say, “I’m sending tons of fuel to the engine.” The mixture gets the final say, reducing that flow (leaning) or leaving it alone (full-rich position). In that manner, the fuel/air mixture can be set for conditions, whether taking off from a sea-level Florida beach town or the dizzying heights of Leadville, Colorado.

Mountain flying

At higher altitudes, pilots lean the mixture before takeoff to assure maximum power. A pilot who didn’t do that made an emergency return to Leadville, Colorado (elevation 9,927 feet), to have his engine checked. It took awhile—a long while—to convince the lowlander that it was the pilot, not the engine, who was to blame. Full throttle with a full-rich mixture position is too rich at 9,000 feet, and reduced power is the result.