On Instruments: Transitioning Up and Down

Flying through altitudes and levels

In other words, when you climb into Class A airspace, your altitude switches from one based on your height above local, surface-based barometric pressure readings to an altitude based on a common pressure surface of 29.92 in Hg (dubbed “QNE”). Now you’re flying along the height of a constant pressure level. But so is everyone else up there, so if the height of the pressure surface rises (as it does when temperatures are higher than standard) or falls (when temperatures are colder than standard) there will be adequate vertical separation as long as everyone maintains his or her assigned altitude. Above FL180, a 1,000-foot vertical separation is the rule for IFR operations.

When the surface-based atmospheric pressure (called “QNH”) in the local area drops below 29.92 in Hg, then the lowest usable flight level is raised from FL180 to FL185—or higher—because otherwise, someone flying IFR at, say, 17,000 feet msl may be closer than 1,000 feet to aircraft flying in the lower flight levels.

Descending through FL180, it’s time to change from 29.92 in Hg to whatever the local altimeter setting might be. So in North America, the boundary between QNH and QNE and positive-control Class A airspace and the airspace below it is easy to comprehend. There’s only one boundary—and it’s nearly always 18,000 feet msl.

But I’m thinking that many pilots long for the day when they’ll get a chance to fly in foreign airspace. I hope you do. Altitude-wise, that’s where the game changes, whether you’re flying IFR or VFR.

Transition altitude

Let’s say you’re taking off from an airport in Europe. When you receive the airport weather, you’ll be issued a local altimeter setting, just like in the United States. You’ll use that altimeter setting for takeoff and the initial climb, but at some point you’ll cross the boundary of what’s known as the transition altitude. That’s when you’ll make the change from a QNH altitude based on the airport’s sea-level setting to a standard altimeter setting of 29.92 in Hg. (Or, more likely, 1013.2 millibars, which is the equivalent.) Again, just like the United States.

In most cases, however, this change doesn’t often come at altitudes as high as 18,000 feet msl. On the contrary, transition altitudes can be as low as 3,000 or 4,000 feet msl. In Germany, for example, typical transition altitudes run around 5,000 feet msl. In the United Kingdom, it’s usually 3,000 feet, but 6,000 feet in the London area. Transition altitudes can be raised when local altimeter settings or temperatures drop below their standard levels.

Transition level

As for descents, foreign airspace uses what’s called a transition level to mark the change from standard to local altimeter settings. The transition level is the lowest flight level available for use above the transition altitude, and it’s published on approach plates. The height of the transition level depends, as with transition altitudes, on terrain, local altimeter settings, and temperature. Air traffic control doesn’t want airplanes coming out of the flight levels into high-to-low, look-out-below issues. So transition levels are not set in stone. As a procedural matter, ATC may issue an altimeter change at its discretion to a pilot in a descent. That amounts to a directive to switch from the standard altimeter setting to a local one. Comply with it, and, presto—you’ve left the flight levels.

It can be confusing to keep the terms straight at first, so a memory aid helps. The “A” in transition altitude points upward, a reminder that these apply to climb situations. The “V” in transition level points downward, a reminder that leaving a transition level involves a descent.

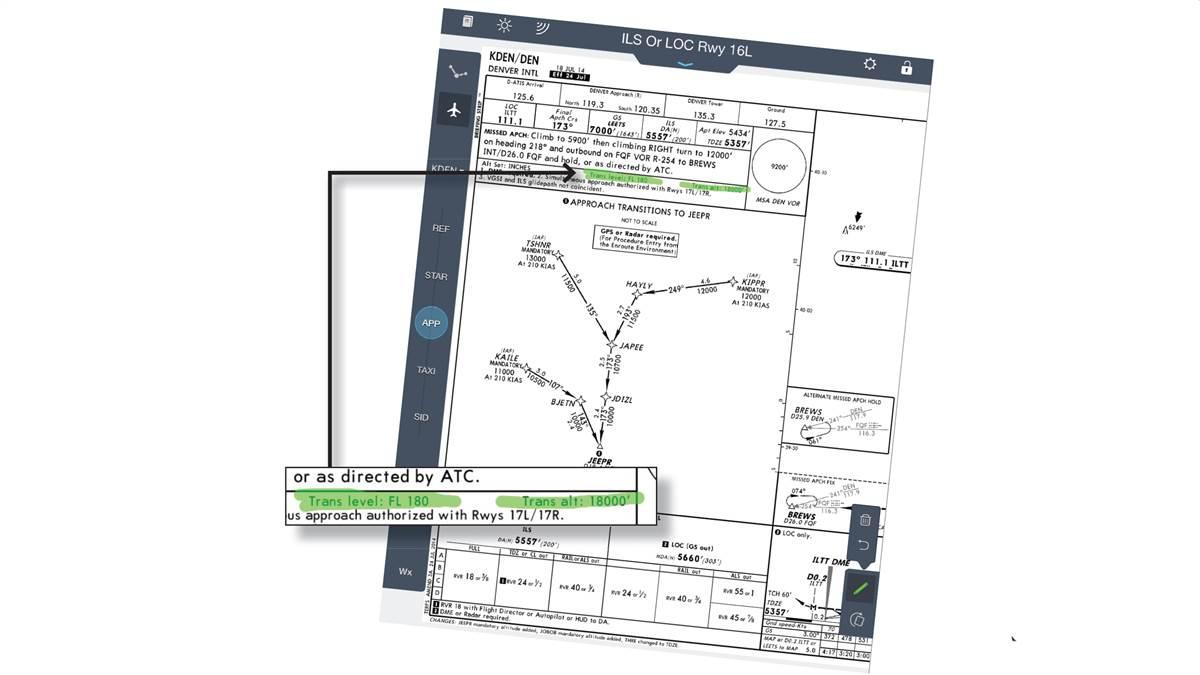

For all the talk about a united European community, its airspace still reflects a hodgepodge of transition altitudes and levels. There’s an initiative to combine them, United States-style—into one common altitude. But it’s been slow going, and until the Single European Sky Air Traffic Management System is fully implemented, it’s unlikely that local ATC jurisdictions will give up their practices. As for the rest of the world, expect the status quo to persist. Luckily for North American pilots flying domestically, 18,000 feet and FL180 remain transition altitude and transition level, all rolled into one. Still, there are hints that the terms may become internationalized. Jeppesen, for example, now publishes transition levels on United States approach plates. It’s always FL180, so we’re lucky that way. But be prepared if you fly to a foreign locale.

Email [email protected]