Fly the wild side

Fly the wild side

Photography by Chris Rose and the author

Illustrations by Charles Floyd

A pilot’s logbook records many memorable flights, some of them unforgettable. The first solo, the first checkride, and perhaps the first passenger will be among these. And a first aerobatic flight is almost certain to make the list.

A sequence card (far left) lays out the maneuvers of a competition routine in lines and dots. Diana and Mike Neuman prepare their parachutes at the U.S. National Aerobatic Championships (above). The G-meter (left) following a Sportsman flight shows the maximum positive and negative loads, as well as the current reading of one G.

“You don’t know what to expect,” recalled Diana Neuman, less than a year after her first inversion, when she stood—as a competitor—on the ramp of North Texas Regional Airport at the 2015 U.S. National Aerobatic Championships. “I was really nervous about throwing up in the plane.”

Like many aerobatic flights, it began with a safety check—a half-roll to inverted that confirms the safety harness is secure, and gives any neglected loose objects in the airplane a chance to make themselves known.

“The world is just so different,” Neuman recalled. “At the same time, this is the greatest thing ever. That was the moment.”

For many pilots, “the moment” is a crossroads—a decision point that can change a flying career. Not everyone finds it to be the greatest thing ever, and experienced instructors will get to know their students (or passengers, if the mission is simply a thrill ride) before the flight. They’ll also spend time talking about the plan, what will happen each step of the way.

“Every ride is different because every individual is different,” said Rob Holland, hours after winning an unprecedented fifth consecutive national championship in powered aerobatics (gliders are scored separately). Holland, the most accomplished U.S. pilot on the world competition circuit in a generation—and among the most popular airshow performers in the country—has given many rides to pilots and local media personalities, some very simple and others a bit more dynamic.

“You just feel them out as you go,” Holland said. “See how they’re feeling, see what they like, see what their expectations are, and plan accordingly.”

For many people, particularly those who have some pilot training already, that first aerobatic flight will produce the moment that begins a lifelong journey in pursuit of an elusive goal: perfect maneuvers. Aerobatic pilots are, generally speaking, consummate stick-and-rudder pilots—particularly those who follow Holland’s lead and join the International Aerobatic Club, which sanctions competitions around the country. To start that journey off right, the IAC website offers a list of instructors who teach aerobatics; any of them will train pilots to compete, or just have fun, depending on preference.

Sooner or later, most will make a pitch to try a contest. It goes something like this: The people are great, the welcome is warm, and even if you don’t come home with a trophy, you’ll make tremendous gains in confidence, airmanship, and comfort in the airplane at any attitude. In time, and it may not take much time, there will be no more “unusual attitudes”—only “attitudes.”

Safety first. One particularly strong argument for seeking out an instructor who both teaches and participates in IAC competition flying for your aerobatic introduction is that he or she will share the obsession with safety that courses through the competition aerobatic community. To state the obvious, there are risks involved in pushing an airplane, even one designed for aerobatics, toward its limits, and the IAC rules are full of measures and specifications designed to mitigate risk. For one, the minimum altitude for beginners is 1,500 feet above ground level (agl), which leaves more time and space than you might think to correct a bad attitude—be it the airplane’s or the occupant’s.

While contest flights are a bit more regimented than a typical first aerobatic flight with a local instructor, IAC contests begin with a detailed technical inspection of every airplane, including an important piece of safety equipment: the parachute. You probably will notice your instructor spends a bit more time on the preflight than you’re used to, particularly the briefing. That briefing will include a lot of detail on what to expect, and what to do if things don’t go as expected.

Along with the parachute comes a detailed briefing that covers the procedures for egress, parachute deployment, and how to steer and land a parachute.

Relax. This is why you found an experienced instructor, someone who can handle the airplane whatever happens, and give you the freedom to fly it yourself with a little guidance—which is usually Holland’s approach.

“[I] usually just start off with a couple rolls,” Holland said. “I’m mostly letting them fly the airplane and talking them through it, because they get more out of it that way.”

That’s true from both a learning standpoint—students quickly notice that basic maneuvers often “click” when they fly the maneuver themselves—and a psychology standpoint: Having hands and feet on the flight controls makes most people feel a sense of control, and reduces or eliminates the surprise of “Hey, we’re upside-down all of a sudden.” After all, you did it yourself.

“If they want to see anything beyond that, I’ll be happy to demo it,” Holland said. “Basically it’s about letting them fly.”

No matter whether your first aerobatic experience comes early or decades into your flying career, it will be impossible to predict how you react until you try it. Diana Neuman’s husband, Mike, had a commercial pilot certificate, instrument and rotorcraft ratings, and about 20 years of flying before he took the plunge. The couple had volunteered at a local aerobatic contest, the Apple Turnover in Ephrata, Washington—and if you don’t want to be tempted by an aerobatic airplane ride, volunteering at an IAC contest is a mistake. Mike Neuman was not at all sure he wanted to be tempted. He had not enjoyed spin training with his father one little bit, and “it stuck with me.”

Throughout his flying career, when encountering turbulence or a couple of Gs, “every single time it would affect me,” Neuman said. The somewhat cramped confines of a typical aerobatic airplane, even the venerable American Champion Decathlon, made matters worse, Neuman added. It wasn’t until he decided to start training in earnest that he felt a breakthrough and became comfortable with unusual attitudes.

“Being in control was the difference,” Neuman said. Fly a loop, roll the airplane over, “you can do it at your own pace. I could start to understand the world around me.”

Neuman found this comfortable spot at Four Winds Aviation at Aero County Airport in McKinney, Texas, conveniently located a half-hour south (by Super Decathlon) of the home of the national aerobatic championships. Four Winds even trains primary students, like Diana, in the Super Decathlon, giving them tailwheel experience from day one. The unflappable chief instructor, Eric Forsythe, said students gain a great deal, including confidence, from that.

Neuman found this comfortable spot at Four Winds Aviation at Aero County Airport in McKinney, Texas, conveniently located a half-hour south (by Super Decathlon) of the home of the national aerobatic championships. Four Winds even trains primary students, like Diana, in the Super Decathlon, giving them tailwheel experience from day one. The unflappable chief instructor, Eric Forsythe, said students gain a great deal, including confidence, from that.

Diana passed her private pilot checkride in November 2014; she and Mike began training for aerobatics the following spring.

“I was doing it in parallel with her,” Neuman said. They started in the Super Decathlon, and “the point of that was learning to do energy management well. It really makes you focus on the details.”

The Decathlon lacked oomph, however, and the Neumans soon bought an Extra 300, although they left it at home for the 2015 national championships and instead rented the Four Winds Extra for the contest. They arrived with 110 hours and 28 hours in the Extra, respectively, having made great strides as pilots in a relatively short time. It was the fifth IAC contest for both, and they already were smitten with the sport.

Mike Neuman said all of that has made him more confident in any airplane, including the Mooney they own. “I didn’t feel like I really knew how to fly,” he said. “The more I learned…I didn’t know how to fly. It made me feel like I was a better pilot afterwards.”

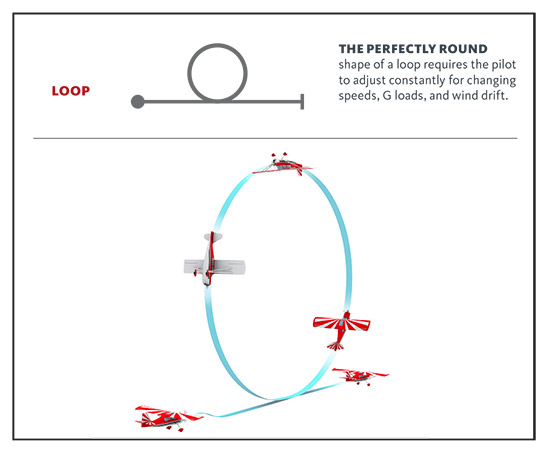

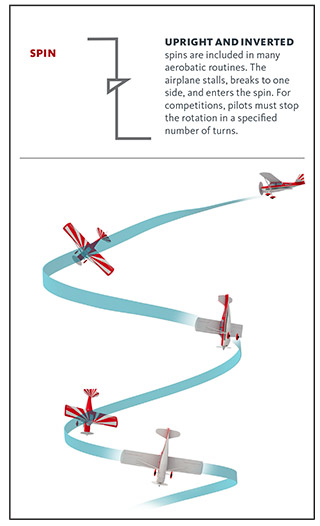

Among the skills that must be mastered to compete at the Sportsman level, which is the second of five competition categories in the IAC progression, are stopping a spin on a heading (although spins have been eliminated from the compulsory or “Known” program for 2016); flying a loop that is actually round (results may vary); and a variety of combinations of half loops, rolls, half-rolls, and more.

All of that, Mike Neuman said, has many benefits. When precision becomes second nature, a narrow runway or a gusty crosswind is not so daunting. Aerobatic pilots are the “best GA pilots around,” Neuman said. “That should be the story that we’re telling.”

There is also the matter of fun, and, for some—particularly pilot Rob Holland—a pretty good career, as well. His office has quite a view.