When investigators sift through the details of approach and landing accidents, especially those with roots in unstable approaches, they’re often perplexed at why so many pilots refuse to execute a go-around when many signals seemed to tell them that coming back around for a second try was the safest option. Groundbreaking research conducted by the Flight Safety Foundation looked closely at more than 70 approach and landing accidents in turbine aircraft over the past few decades, and found that fully 75 percent of these mishaps were caused by a combination of poor judgment and poor airmanship.

The research showed that signs of impending chaos were pretty clear by almost anyone’s measurement system and included excessive localizer or glideslope deviations, an absence of visual references at decision height, confusion regarding the aircraft’s actual position in space—and, not surprisingly, a lack of understanding of how to operate the aircraft automation during an unexpected go-around.

Despite the constant chatter about unstable approaches, go-arounds are actually rare events, even in training, which reinforces a lack of proficiency in an event that’s classified by the industry as a normal maneuver. Imagine the effect of only practicing landings once or twice a year. Most business aviation flight department standard operating procedures (SOPs) clearly outline the conditions under which crews are expected to discontinue an approach, and yet landing accidents from unstable approaches continue in direct violation of company procedures. So why do so many pilots insist on landing when, in retrospect, a variety of signals seem to be telling them the best option is to give the approach a second try?

At the Flight Safety Foundation’s recent International Air Safety Summit, presenters Bill Curtis and Tzvetomir Blajev looked at the psychology of systemic and chronic noncompliance with SOPs and explained that although 65 percent of all accidents are related to approach and landing, only 3 percent of the pilots executed a go-around during the unstable approach that preceded the accident.

The research pair learned that pilots actually have little incentive to comply with SOPs, because the repercussions for violating procedures are few. There were also pilots who thought go-around criteria were unrealistic and hence not really a violation of any standard.

From a human-factors perspective, Curtis and Blajev found that pilots guilty of ignoring unstable approach warnings often also tended to be poor communicators with the other cockpit crewmember. Some critics of pilot behavior in approach and landing accidents were not surprised to also learn at the summit that many of the pilots who chose to land out of unstable approaches scored much lower than their colleagues on every single component of situational awareness.

The research also discovered that despite a plethora of human factors training over the past few decades, some crewmembers still feel uncomfortable challenging the other pilot and simply watch these sometimes-fatal events unfold in front of them.

Is pilot training the problem?

Has the industry contributed to pilots’ seeming indifference to unstable approaches—and provided an unwritten OK to say, “I think I can make this work,” much too often in normal operations? Any pilot fresh out of recurrent training knows he or she will experience a go-around at decision height during a single-engine approach, or when the instructor points out a truck entering the runway at the last moment. Is our training system unintentionally setting pilots up to think that these are the only likely times a missed approach will occur? Pilots aware of this system weakness have the option of asking for specific training, even if our regulators and providers don’t always make it easy to fly outside-the-box maneuvers. But then, there is that awkward explanation that go-arounds are normal maneuvers.

How often do turbine crews experience a go-around just after the pilot flying calls for landing flaps at the final approach fix, just for practice? Missed approaches also occur with some regularity in good weather when the tower calls for it on a three-mile final. Are we practicing go-arounds from that point? ATC might unintentionally create the need for a go-around by keeping an arrival too fast or too high for too long for the crew to stabilize aircraft on final.

Specific go-around training, especially out of unstable approaches, needs to highlight that not every go-around requires full power and a deck angle that points the aircraft at the stars. Go-arounds from a three-mile final, for example, especially when an aircraft is light, can create high-thrust-to-weight problems that demand significant pitch and trim changes as the crew hunts for the best power setting.

Within seconds, a rote response to a go-around could result in an aircraft climbing at 2,500 fpm when the situation only required a short climb, or possibly even leveling off at the current altitude. Flap overspeed events during go-arounds are another indication of the need for better training.

The Flight Safety Foundation believes pilot training should include a focus on states of readiness as they refer to missed approaches, strategies the Flight Safety Foundation refers to as being “go-around prepared” and “go-around minded,” before each and every approach—not simply when the weather is down. Consider again that some pilots think unstable approach and, hence, go-around criteria are unrealistic. The foundation’s research found there is indeed a lack of understanding and proficiency by some pilots for what constitutes a stable approach, a problem the foundation has attempted to fix with its Approach and Landing toolkit. The toolkit offers users significant signposts to accurately point out how well or how poorly an aircraft is prepared to land.

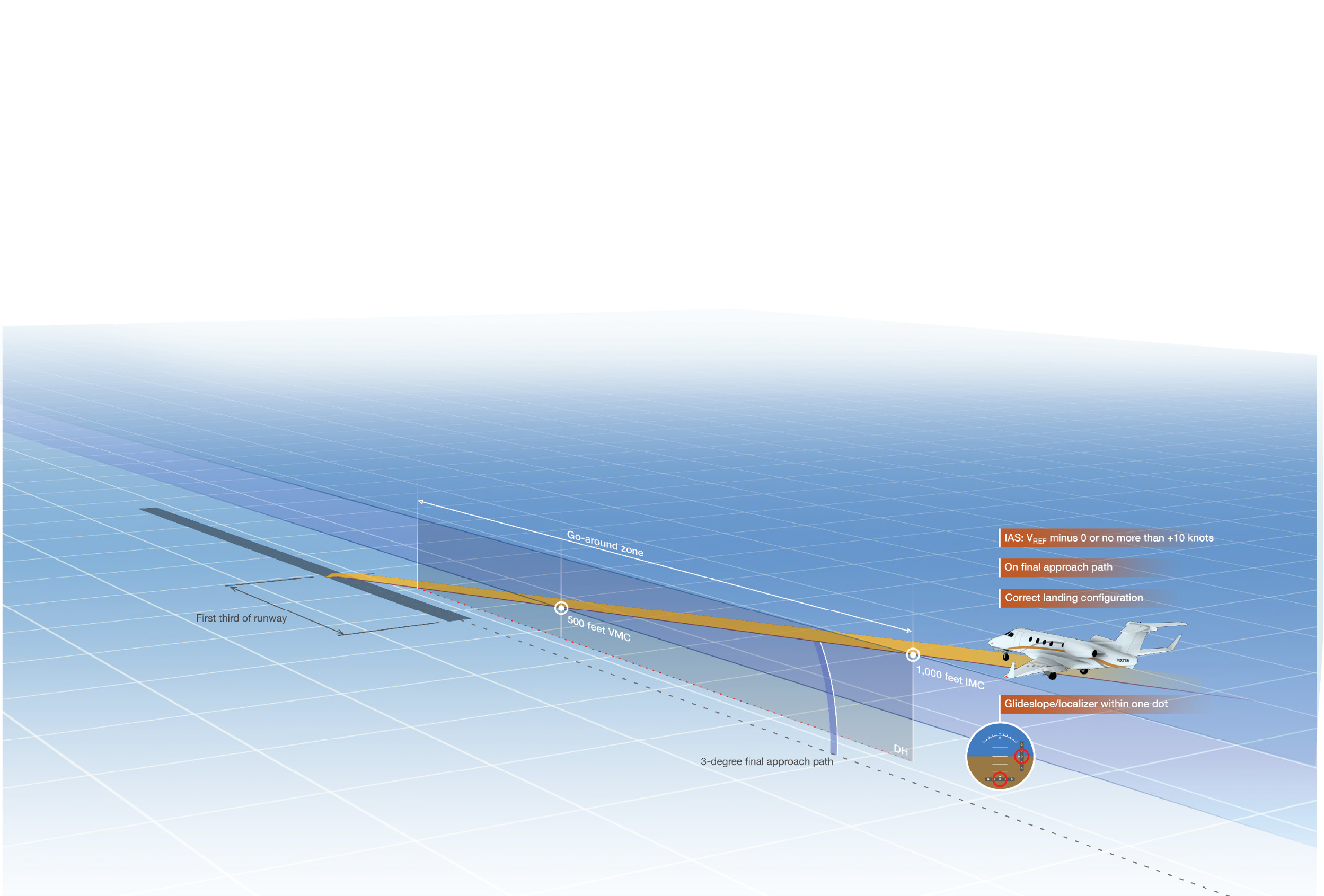

The toolkit says that during instrument conditions, a turbine aircraft should be stabilized on final approach at the 1,000-feet-above-airport elevation point, while during visual weather the final decision can be held until 500 feet above the ground. Once inside either of these two reference points, the remainder of the approach should demand only minor changes in heading or descent rate. The indicated airspeed should remain close to the final approach reference speed using only minor power changes. Following these guidelines should allow the aircraft to touchdown in the first one-third of the runway. Anything, absolutely anything, that causes the aircraft to deviate from any of these parameters should be a clear message to the PIC that a go-around is the only safe alternative, especially when the pilot starts thinking he or she can still make it all work.

If the aircraft is being flown single-pilot, an unstable situation demands even more that the PIC understand the guidelines for when it’s time to go around. With two pilots aboard, the pilot monitoring must feel comfortable enough to call for a missed approach, and the company SOPs should support the call. A turbine airplane’s Terrain Avoidance Warning System blaring “Sink rate, Sink rate,” or “Terrain, Terrain,” should only be considered as the PIC’s final warning of impending disaster—not the first.

Robert P. Mark is the publisher of JetWhine.com.