Letters from our September 2016 issue

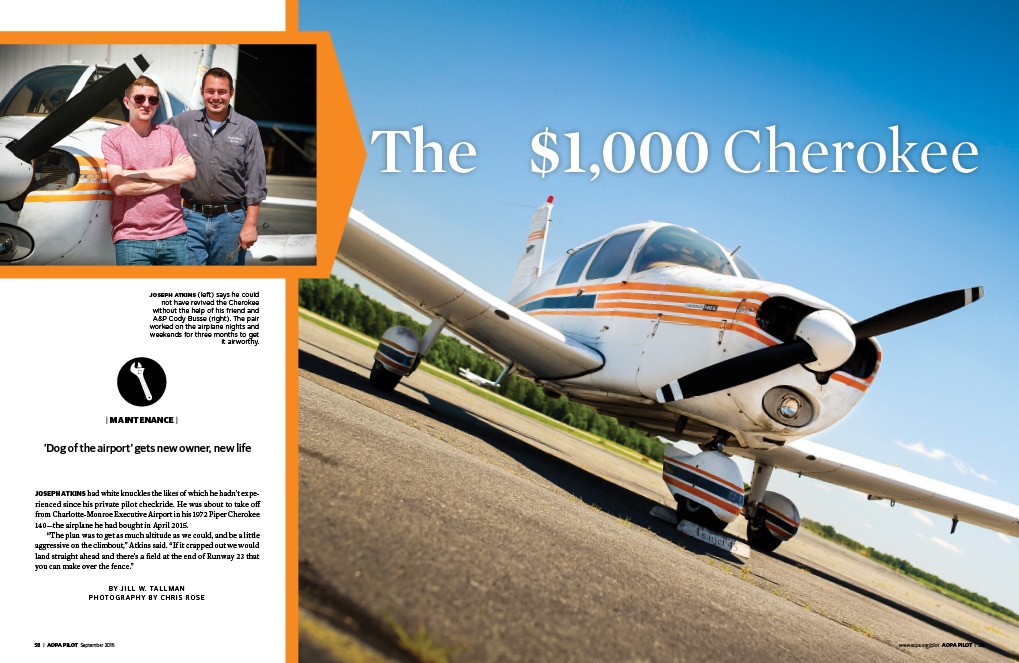

The $1,000 Cherokee

Arriving home from work yesterday, I saw the September issue of AOPA Pilot sitting on the kitchen table so I made a quick grab and headed to the recliner for some reading. After a few minutes of thumbing through the pages I ran across Jill Tallman’s “The $1,000 Cherokee.”

Arriving home from work yesterday, I saw the September issue of AOPA Pilot sitting on the kitchen table so I made a quick grab and headed to the recliner for some reading. After a few minutes of thumbing through the pages I ran across Jill Tallman’s “The $1,000 Cherokee.”

Wow, this excellent piece brought back some fantastic memories. N2886T is the aircraft in which I completed my first supervised solo at the now-gone Alameda airport in Albuquerque. The date was May 19, 1976, during my sophomore year of high school, and my morning aerial adventure made me late for class so I was sent to the principal’s office. When asked for an excuse, I told Mr. Barefoot about what had just transpired and held out my certificate of solo flight. He looked it over, gave me a smile, a handshake, and handed me a hall pass.

The last time I saw N2886T was on May 21, 1992. I had flown a Skylane to Tupelo, Mississippi, from Atlanta and noticed it sitting in an area for permanent tiedowns. I walked over to where she was parked and spent time reminiscing about that special day. Thanks for helping me make another flight down memory lane and I wish Mr. Atkins many years of great times and safe flying with the Cherokee I’ll never forget.

Mark W. McManaman

AOPA 1097742

Atlanta, Georgia

“I thought Jill Tallman’s article on the $1,000 Cherokee was great. The guy in the article was extremely lucky to get all the help he did and meet people willing to help him out for the sake of aviation.” Alan Varner, AOPA 5304250, Tucson, ArizonaSavvy maintenance

With a few decades of mechanical experience, including stints with race cars and bikes, I found Mike Busch’s description of modern vehicle repair far too accurate to be amusing. When it comes to land machines I have the luxury of time and the inclination to ponder how things work, going through the process of developing a differential diagnosis so I can minimize cost by fixing only what’s broken.

While bench racing with the owner of a Porsche shop one day, I noted he was swapping out a rather expensive part (aren’t they all on a Porsche?) without doing much trouble-shooting. I had watched as he worked up to this point and was surprised when he cut the diagnosis short. I asked why he hadn’t done this or that to narrow the possibilities or confirm what he was replacing. As he finagled the old part out of the engine bay, he acknowledged my point but explained that labor costs being what they were (Silicon Valley), for many jobs it was cheaper for him to replace a part he probably could fix than take the time to make the repair and reinstall. He also noted that using a new part shifted some of the responsibility for a future failure to the part manufacturer. “It’s just easier,” he sighed.

I wonder how much of this scenario applies to A&P work? Mike’s closing observation always holds true: If the tech can’t explain in logical, comprehensible terms why he chose to do what he did, think hard about where to have future work handled.

Stan Baldwin

AOPA 9341253

Palo Alto, California

Waypoints

I read Thomas B. Haines’ column on do-it-yourself maintenance and wanted to provide another perspective. While I completely concur with the concept of understanding as many details of all aircraft systems as possible, I have always had my aircraft oil changes performed by my maintenance shop. I prefer that a well-trained expert gets their eyes on my aircraft as much as possible. I would expect that my shop’s technicians will notice anomalies better than I would. Perhaps they would spend less time looking around than I might, but experienced eyes should notice more in that time. And, given that my aircraft mechanic shop rate is about half of my automobile dealer shop rate, I feel it is a great value to take the airplane to my mechanic every 50 hours.

Kate Proctor

AOPA 1152371

Carlsbad, California

The new normal

Chip Wright’s “The New Normal” brought the memories flooding back. We operated a Falcon 900 out of White Plains, New York, under our own Part 135 certificate. When flights resumed on September 13 for air carriers we found ourselves dead-heading to Burbank to rescue stranded travelers. Departing the next day, we made stops in Oakland and Las Vegas to bring a full boat back to White Plains. The flight was routine and the passengers happy to be going home. Now night, the arrival brought us in over the Catskills. From there, on another crisp clear night, we got our first sight of the city. The smoke rising from the ruins seemed to glow—a deeply stirring image I can picture now.I never went down to Ground Zero. Couldn’t bring myself, and haven’t been to the memorial, either. Now retired and 15 years later there is no closure for me. Too many unanswered questions.

David Smith

AOPA 861716

New York, New York

Hangar Talk

Photographer Mike Fizer is the son of former U.S. Air Force fighter pilot Bob Fizer, who served from 1952 until 1971. The elder Fizer flew the F–100 Super Sabre for most of his career, retiring in Wichita. His son naturally grew up around aircraft and, although not a pilot himself, more aircraft have flown past the lens of his camera than most of us will fly in our lifetimes. His father’s influence contributed to his affection for aircraft and to his personal project, interviewing surviving F–100 pilots on video (he also videotaped his dad for a Father’s Day tribute on AOPA Live). Most of the pilots have been members of the Super Sabre Society, which has as its mission to preserve the history of the aircraft and the men who flew it. A recent Super Sabre reunion in Fort Wayne, Indiana, included the opportunity to purchase rides in a F-100F, a two-seat model used in training and owned by pilot Dean Cuttshall. Mike and his dad drove to the reunion and, along with AOPA ePilot Managing Editor Alyssa J. Miller, interviewed many surviving pilots (see “One More Time,” page 78). “Dad and I drove to the reunion and spent the week covering the event, enjoying the camaraderie of the members,” says Fizer. “Because of his health at the time, my father didn’t have the chance to fly the aircraft, but he conducted the interviews when Alyssa wasn’t available.”

Photographer Mike Fizer is the son of former U.S. Air Force fighter pilot Bob Fizer, who served from 1952 until 1971. The elder Fizer flew the F–100 Super Sabre for most of his career, retiring in Wichita. His son naturally grew up around aircraft and, although not a pilot himself, more aircraft have flown past the lens of his camera than most of us will fly in our lifetimes. His father’s influence contributed to his affection for aircraft and to his personal project, interviewing surviving F–100 pilots on video (he also videotaped his dad for a Father’s Day tribute on AOPA Live). Most of the pilots have been members of the Super Sabre Society, which has as its mission to preserve the history of the aircraft and the men who flew it. A recent Super Sabre reunion in Fort Wayne, Indiana, included the opportunity to purchase rides in a F-100F, a two-seat model used in training and owned by pilot Dean Cuttshall. Mike and his dad drove to the reunion and, along with AOPA ePilot Managing Editor Alyssa J. Miller, interviewed many surviving pilots (see “One More Time,” page 78). “Dad and I drove to the reunion and spent the week covering the event, enjoying the camaraderie of the members,” says Fizer. “Because of his health at the time, my father didn’t have the chance to fly the aircraft, but he conducted the interviews when Alyssa wasn’t available.”