Never Again: Suddenly PIC

Who’s flying the iced-up Baron?

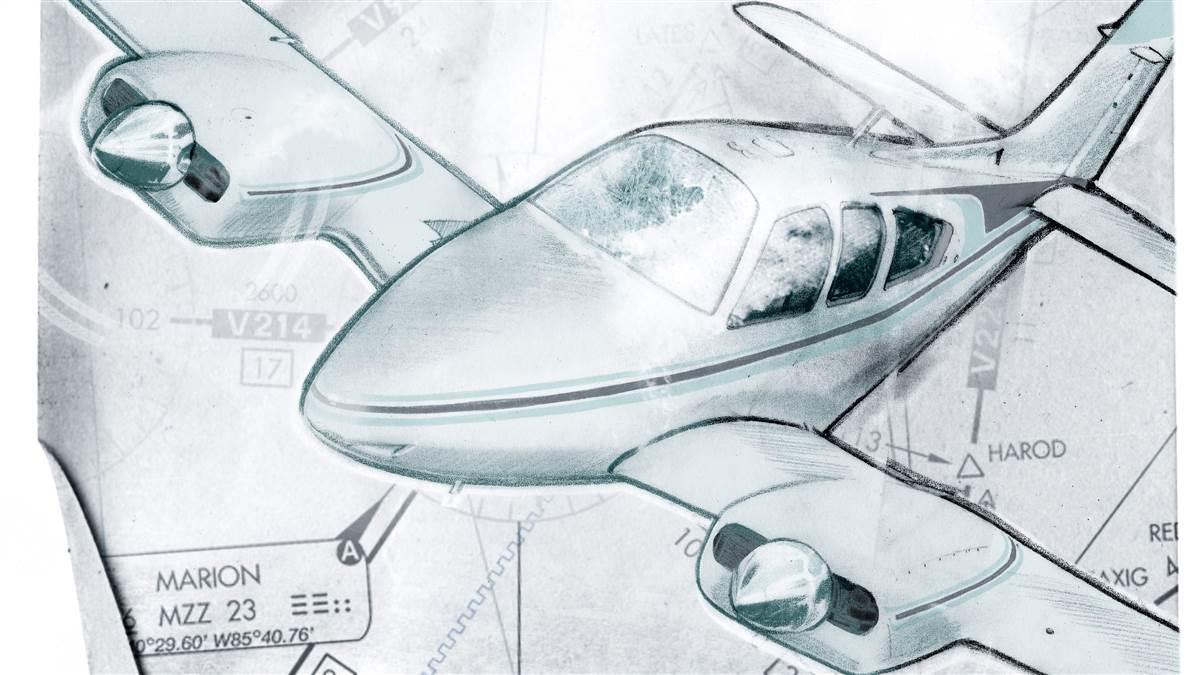

On a blustery early March day, “Mike,” one of my former students, and I decided to fly from Cincinnati’s Lunken Field to Muncie, Indiana. We were bringing a third pilot to check out a candidate airplane for a partnership in a Socata TBM 700.

Flying a Baron 58, Mike had planned a 20-minute flight. Lunken weather was just below freezing on the ground with an 800-foot ceiling. The winds on the ground were at 18 knots or so from the west-southwest. I checked the weather at Muncie out of curiosity, since I was not pilot in command, and noted that the weather was about the same as it was at Lunken—with winds that would give us a crosswind landing on both possible runways at Muncie. No big deal.

We climbed into the Baron without much discussion and shortly entered the cloud layer. Immediately, the Baron started collecting ice on the windshield, wings, and empennage.

“Did you get a briefing on the expected weather en route?” I asked Mike.

“Well, sort of,” he replied. I knew what that meant. We were flying into the unknown.

At this point, we were committed to at least vectors northbound to get back on the ILS 21L to return to the field. Although not PIC, I could tell that the safety of the flight unexpectedly was already in my hands.

We continued our climb and received vectors to turn northbound. By 3,000 feet, the windshield was already completely covered with a thin layer of clear/mixed opaque ice. I have flown many hours picking up ice in many kinds of airplanes, and I had never seen a case like this—or since. The windshield was completely covered from top to bottom and side to side. There was no forward visibility at all.

The airplane did not have a hot plate for the windshield but did have an alcohol dispersal bar for the left side—better than nothing, but not by much. The boots were working adequately for the wings and empennage. At least we could keep flying. Landing was going to be a future problem.

At this point I’m thinking, OK, let us climb above this cloud layer and maybe we canlose some of this ice on the windshield. At the same time, we heard ATC tell another pilot the tops were at 9,000 feet. Mike said, “Oh, not worth climbing above it as we are only 50 miles away.” Well, maybe, but it could be five miles too far.

We were now at 4,000 feet and slightly north of the city. ATC cleared us direct to Muncie. We were still undecided as to the best course of action, as we were about halfway between each airport. We turned direct, but now a strong headwind meant that what should have been a 16-minute flight was going to be 30 minutes. OK, decision made. We could not continue picking up more ice on the windshield for that duration, perform an instrument approach, and complete a crosswind landing without forward visibility.

The odds were not stacking up in our favor. The pilot in the back, eyes wide, heard us talking and looked at the ice accumulating on the empennage and popping off with the cycling of the boots.

“This is not good. I’d rather return to our known home field,” Mike said. The backseat passenger seemed relieved. We informed ATC of our intention to return. They gave us vectors to turn eastbound to intercept the ILS 21L at Lunken. Winds to our back, we were intercepting the localizer almost immediately. I told Mike as soon as we got near the final approach fix we would turn on the alcohol bar and hopefully get a clear enough spot through the windshield to see to land. We turned on the alcohol, but it was too cold and the bar was not pumping out enough alcohol fast enough. All we got was a damp, three-by-six-inch opaque patch on the very bottom of the windshield. This was not going to help at all.

A third of the way down the ILS, I asked Mike, “Are you ready to do the landing?”

“Oh, no, you can do it,” he said.

As we had no forward visibility, the only possible way to land the Baron was to sideslip her to the left at the near the end of the ILS 21L approach so that I could see the runway. Breaking out, three-quarters of a mile or so out, I tried to sideslip to the left to see forward. We had ice on the wings and no time to try too many possibilities.

I requested to land on Runway 25, which I could see on my right side. I kept the right edge of Runway 25 in sight and made a sweeping, descending right turn to land at a mentally measured centerline to the left of the grass. I did not flare. I flew her right to the ground, taking no chance she would just out and out stall in the flare. I taxied into the FBO by following the grass edge on my right and was glad to shut down. Everyone simply said their goodbyes and we went our separate ways, with the thought that we would try again at a later date.

A few days later I talked to Mike and said it must have been a little bit scary with me landing his airplane without him being able to see forward at all. “Oh, I had no fear, I knew you could land her safely,” he said. Certainly a vote of confidence, but I was thinking of Frank Borman’s quote, “A superior pilot uses his superior judgment to avoid situations which require the use of his superior skill.” Slightly revised for our situation, “A superior pilot uses his superior judgment so he does not have to depend on his former instructor’s superior skills.”

Instructors are held to higher standards whenever they fly with other pilots, even if the flight starts out with someone else acting as PIC. It behooves all instructors to get complete briefings before any flight for the safety of all, and have a discussion on any relevant safety issues before departure. Otherwise, one might find the duties of PIC suddenly handed over, as they were on that day.

Roger J. Pelletier is a flight instructor and contract corporate pilot in Cincinnati, Ohio. He has an airline transport pilot certificate with CFII and MEII ratings. hours.