Flight lesson: Flip Flop

By Robert M. Lee

On a beautiful summer morning in Montana, I was flying solo and practicing power-on stalls.

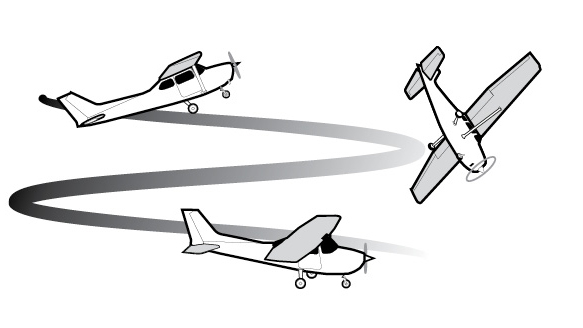

One moment I was looking past the cowling on my Cessna 152 at the big Montana sky as the airspeed dropped and the airplane began to buffet. In the next instant, to my surprise, the little Cessna seemed to flip over on its back, and I was looking at a windscreen filled with the Montana prairie.

My first thought was Bob, you have bought the farm. Fortunately, that first thought was immediately followed with Neutralize the controls, use full rudder opposite to the direction of the spin to stop the spin, and when the spin has stopped gently start pulling up the nose to recover from the dive.

The process worked as advertised—except my airspeed was well into the yellow arc and increasing. Only then did I realize that I had skipped the first step in the spin recovery procedure: I had forgotten to close the throttle. With throttle closed, the rest of the recovery was uneventful. I had to be careful not to overstress the airframe. This was a topic covered at a recent flying club safety meeting.

The remainder of the flight was flying straight and level as I struggled to regain my composure. I then performed a few power-off stalls and recoveries before returning to Great Falls International Airport for an uneventful landing.

What had gone wrong? I replayed and discussed the incident with my instructor following the flight. The assessment was that I must have been careless with the rudder and ailerons and was in a cross-controlled condition when the stall broke. I had unintentionally put myself into a textbook spin entry without an instructor on board to help. Fortunately, I had remembered the spin recovery procedure and was able to apply it successfully, if not perfectly. I was surprised at how quickly and clearly the instructions were recalled. Everything seemed to be in slow motion, and it was like listening to a recording of the instructions. It pays to memorize, and to be prepared for the unexpected.

What did I take away from this experience? There are several important lessons. First, do not put yourself into a situation in which you have your first spin without an instructor on board. This means paying attention to your flying to make sure that you keep the ball centered and do not cross the controls when practicing stalls. There is no substitute for awareness.

Next, always give yourself an extra margin of altitude to recover if things go wrong. If I had been at the minimum safe altitude set by the FAA for practicing stalls, I might not have had enough altitude to recover, especially since I missed the initial step to close the throttle.

Also, memorize the emergency procedures so you can recall them without consulting a checklist. The airlines and the military require pilots to memorize bold-print checklists. General aviation pilots should do the same. None of us is perfect, and we can lose concentration at the wrong time. Finally, look up a good instructor and get some spin recovery training. You will find that spins can be fun when done properly with a qualified instructor.