If you fly in the northern half of the contiguous United States, you might be thinking of moving south as bitter cold sets in and snow, sleet, and ice fall—and sometimes cover runways and ramps. When you see a weather map where a red line is draped across the Southeast with red half-circles pointed north, you might think it’s good news: A warm front is heading north, with warm air following at the surface. Forget it. That “at the surface” is the key thing you need to know about warm fronts.

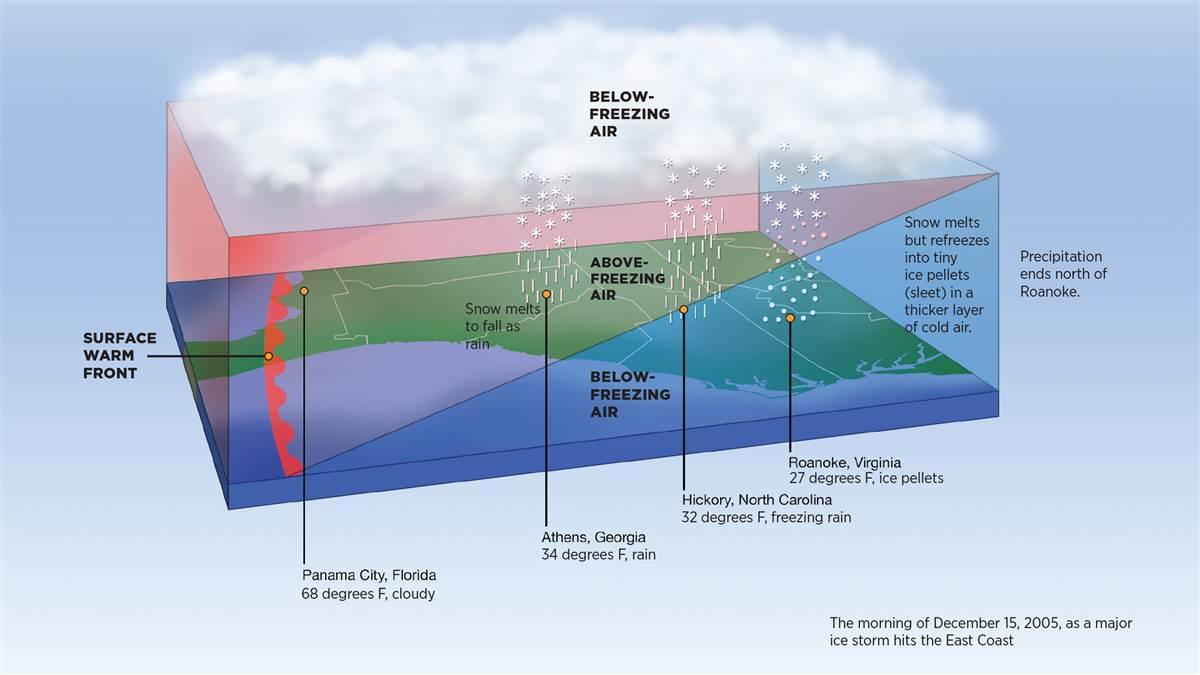

The illustration above is a simplified look at what was happening aloft over the Southeast along a line from Panama City, Florida, up the East Coast to Roanoke, Virginia, the morning of December 15, 2005, when a major ice storm hit the region. The red line with the red half-circles shows only the front’s surface location. Aloft, the front extended more than 500 nautical miles northeast over the Middle Atlantic.

Cold air already in place near the surface and aloft was creating a cold/warm/cold-air “sandwich” over the region. In such a sandwich, snow forms in the top layer of freezing air and falls into the warm middle-level air, where it begins melting. If the layer of warm air is deep enough the snow melts into rain. If the warm layer isn’t deep enough, the raindrops cool below 32 degrees Fahrenheit, but they don’t turn into ice right away; the water is supercooled.

When an airplane flies into supercooled rain, drizzle, or clouds, the water instantly turns into ice when it hits any part of the airplane. Such structural icing disrupts airflow over the wings and control surfaces. It’s one of aviation’s biggest weather dangers.

If the bottom layer of below-freezing air is thick enough the supercooled raindrops will freeze into ice pellets, which are also called sleet. If ice pellets—which are about the size of the tip of a pencil and bounce when they hit—are falling, there’s freezing rain aloft. Don’t even think about taking off.

Weather like this is constantly changing. For example, at Roanoke, Virginia, light freezing rain fell from 5:35 until 6:23 a.m.; snow began mixing with the freezing rain and then turned to all snow two minutes later. Snow continued until 8:56 a.m. when freezing rain began mixing with it. Ice pellets fell from 10:54 a.m. through 2:01 p.m., when freezing rain began falling again until 7:54 p.m.—when the precipitation ended.

During that day, as much as three-quarters of an inch of ice accumulated on parts of northern Georgia and South Carolina, western North Carolina, and southwestern Virginia. The ice pulled down tree limbs and power lines, causing almost 700,000 customers to lose power, as well as causing numerous accidents on icy roads. Both airlines and general aviation were grounded over a large part of the region, including at the busy Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport. All of this from a warm front.