Personal Best

Calculating a formula for fun

For me, it almost always begins with a map. Often it’s a very old sectional, the first one I bought as a student. It’s worn, frayed at the folds, routes and waypoints marked with pencil and felt-tip pen. Short cross-country. Long cross-country. Here is the story of where I’ve been, I think. And here is the story of where I have not.

More important, the map makes me wonder. I wonder about important things, such as distance and fuel, but more often than not I wonder about the edges of what is possible. Could I get there on straight floats? Could I get there in a day? Looking at the airports and grass strips surrounding Hector Field, the Fargo Jet Center, the roads and prairie in North Dakota I call home, I wonder about speed, about records—and, in an odd way, about the silly ways that math can motivate a pilot.

More important, the map makes me wonder. I wonder about important things, such as distance and fuel, but more often than not I wonder about the edges of what is possible. Could I get there on straight floats? Could I get there in a day? Looking at the airports and grass strips surrounding Hector Field, the Fargo Jet Center, the roads and prairie in North Dakota I call home, I wonder about speed, about records—and, in an odd way, about the silly ways that math can motivate a pilot.

I stare at maps and wonder about every place. I look at strips labeled Private and wonder who lives there, what stories they might tell. I wonder who named an intersection PANIC. Mostly, I stare at maps because of what they don’t show, the mysteries they imply, the promise of a darn good story.

Records, even if they’re just a personal best, are a strange motivation. I’m sure this one began with a summer solstice. At how many airports, I wondered, could I land during the daylight hours of the longest day? Could I land in all of North Dakota? This was just a dream, so it didn’t matter that 18 hours of flying might be a bad idea. I also wonder about flying the X–15. That would be a very bad idea. But I do like to dream about the answers.

Then it all got real. Somewhere along the line, and I am sure for a completely different purpose, I heard about what math people call the Traveling Salesman Problem. It’s an exercise in efficiency. If you have X number of clients to visit, Y number of miles apart, what is the most efficient route?

Great idea for cars, I thought. But what about flying?

I looked at the Twin Cities sectional. What if the goal were quantity: the maximum number of stops in a given amount of time? Would the math apply? Two hours, I thought. There was no special magic to the number. Two hours just seemed reasonable. How many airports could I touch with my wheels in two hours?

I called my friend, Nate Axvig, a professor of mathematics at Concordia College, where I also teach. “Nate,” I said, “I have a question.” I explained the idea.

“Oh,” he said, “this is going to be fun.”

Ready?

Fast forward a week or two. Justin Gustofson, CFI at the Fargo Jet Center, is the pilot in command. I’m in the right seat, camera and notebook in hand. Nate is in the back seat, grinning huge. He’s in charge of the clock.

Fast forward a week or two. Justin Gustofson, CFI at the Fargo Jet Center, is the pilot in command. I’m in the right seat, camera and notebook in hand. Nate is in the back seat, grinning huge. He’s in charge of the clock.

Our airplane is a wonderful Cessna 172, tail number N5256S, Garmin G1000 in the panel. And it’s a perfect day for flying. Wind from 300 at 7. Visibility 10 miles. Overcast at 4,200. Pressure: 30.28 inches of mercury. Birds in the area.

“Everyone ready?” Justin asks. We really aren’t doing anything special. We’re just doing something no one else has ever done. Darn good story, I think. We can’t wait to get started. I’d swear we have the giggles.

We roll onto Runway 27 and go wheels up at 3:14 p.m. Nate starts the clock.

Many constraints

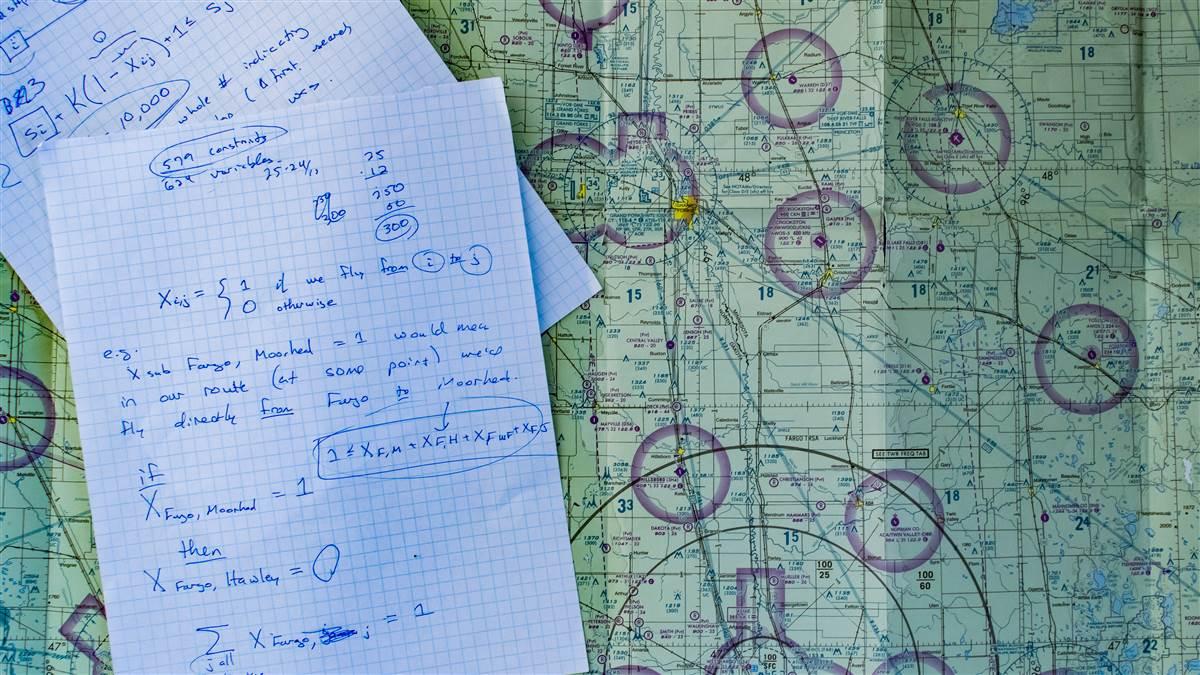

“There are 579 constraints,” Nate said. Constraint is math-speak for an equation. “There are 624 variables, too.”

I’m quite sure my head was nodding. Yes, I thought. Makes sense. Sounds right. We were sitting in the college dining service, detailing our adventure over lunch. I had no idea what he was talking about.

“If X-sub Fargo Moorhead equals 1, that would mean in our route, at some point, we’d fly directly from Fargo to Moorhead.”

This much I got.

“And if X-sub Fargo, Moorhead equals 1, then X-sub Fargo, Hawley equals zero.”

I know he was trying to explain the math to me, the way of how he calculated the most efficient route. I know he’d put the latitude and longitude of every airport into some type of computer program. But nothing is ever as simple as we hope it might be.

Five hundred and seventy nine equations?

Seven minutes

First destination: Moorhead, Minnesota, eight miles away. We climb away from Fargo and turn, reach 1,000 feet agl and 111 knots groundspeed at 0:05:00 on the stopwatch, pull power, and start the approach. We touch at 0:07:40. Already it seems like we are racing, or on a quest, or doing something extraordinary and cool.

We approach Hawley, Minnesota, 13 miles from Moorhead. Touchdown at 0:17:53. Justin is fast getting the flaps back up and the power pushed in.

I’m wondering about the math. We have a 95-knot groundspeed with an 11-knot headwind.

It seems like it takes forever to get to Ada, 23 miles away. We’re counting landings, darn it. Enough of this space in between.

I fear we’re behind schedule already.

Another airplane coming into the pattern at Ada defers and lets us land first. Justin can’t help himself, though. After stating his position, calling traffic in sight, he adds, “We’re setting a record,” he says. “Most number of landings in two hours—every landing at a new field.”

“That’s pretty cool,” the other pilot says. “That sounds like some plan.”

We touch down in Ada at 0:32:34. Then we head toward Hillsboro, North Dakota. It’s our longest leg, at 28 miles.

Follow the rules

There are rules, of course. And guesses.

Every landing had to be at a new airport. I told Nate to skip any airport listed as private, except one where the owner is a friend. Then we had to guess about groundspeed. We had no way to know about winds this far in advance. I had no idea how to average out our airspeed given the fact that we would almost always be in some aspect of approach or departure. Eighty knots, I told him. Just use 80 knots as an average speed. Sounded good to me.

A couple days later we had the result from the number crunching. Ten airports, Nate told me. In two hours, we should be able to touch and go at 10 different fields.

Just 10? I thought. I don’t know why, but I thought there should be more. Two hours is a long time. My heart said we should get 30 airports, maybe more. Then I did the math that even I can do. Ten airports in two hours, in 120 minutes, averages a fresh airport every 12 minutes. Just flying around the pattern in Fargo takes five. If there’s traffic it takes longer. Oh, I thought, this is going to be fun.

Justin put the list into ForeFlight. It drew a circle around Fargo.

Reasons to fly

108 kt TAS, 97 kt GS at 0:42:30.

108 kt TAS, 97 kt GS at 0:42:30.

A bright yellow crop duster appears below us, then heads away. We all take a moment to look. The prairie is unimaginably pretty, I think, even though I’ve flown this ground a thousand times. Just a little bit of altitude and every perspective changes. A solitary tree in a freshly harvested field, a single combine working in a field of corn, the meandering Maple or Sheyenne rivers, the riparian trees along the banks. You can see these from the ground. But you can’t see any of it this way.

There are a thousand reasons why pilots love to fly. There are silly ones, such as trying to make the most landings in two hours—and then there are the important ones, such as the view.

We touch down in Hillsboro at 0:51:26, climb away, bank to the west, and Justin dials our next airport into the G1000. Page, North Dakota, 64G. But the screen gives us nothing. The airport isn’t in the database.

“Well, that’s odd,” Justin says.

The airspace at Page is listed as “Objectionable.”

We tease Nate about actually having to look for an airport, but in truth this is home ground. Neither Justin nor I have ever landed at Page, but we know where the town is. We know where the airport should be, even though it’s very small. Four miles east of town. The runway is only 30 feet wide, 2,600 feet long. According to the airport directory, the asphalt has multiple cracks and the runway pavement is not even. From the air, it won’t look like much at all. A big driveway, perhaps. Maybe just a farm access.

This is old-school flying, despite the fact that Justin has an iPad strapped to his leg. This is also fun. Justin sees the runway first, and all of us are mostly sure it is indeed a runway.

We touch down at 1:05:57. Five different airports in just more than an hour. On schedule, I think. Then I remember how close some of the upcoming fields are. We might be ahead of our planning. In fact, we might be a lot ahead.

Speedy 152

I called the National Aeronautic Association, which is in charge of records and awards. I have one on my office wall: fastest flight across North Dakota in a Cessna 152, a blistering average speed of 77.89 miles an hour. NAA has records for time to altitude, payload, speed, distance, efficiency, speed around the world, and duration.

Surely, I think, there will be a record for most landings in a given period of time. But no such record category exists.

Harvesting corn

There are a thousand reasons why pilots love to fly. There are silly ones, such as trying to make the most landings in two hours—and then there are the important ones, such as the view.We touch down in Arthur at 1:15:07. The grass strip rolls smoothly under our wheels. We could reach out and harvest corn if we wanted to, but that would be a bad idea. We turn south, fly over a massive ethanol plant, race a locomotive across the prairie. We have a five-knot crosswind from the west.

We touch down in Casselton at 1:27:24. Only three airports to go and nearly half an hour on our plan!

We turn east and our groundspeed goes up to 111 knots.

We touch down at West Fargo at 1:36:52 and then my friend Jake’s grass farmstead strip at 1:38:53. Two minutes? I think. Two minutes?

We climb and turn toward Fargo. We’re already just beyond the threshold. There is no traffic to slow us down. No regional jet. No student’s first lesson. We are a rocket. Just for fun we decide on a short approach, the sweeping bank and swirl toward Runway 27.

We touch down at 1:43:44.

“We did it!” Nate says. It dawns on me that the time we did not use is an indicator of the success of the math. Yes, one variable was wrong, and it was my fault. I took a guess at average speed and I guessed too slow. I thought there would be more wind. I thought there would be more traffic. On some other day I might have been right. On this day, we could have added one or two more stops.

OK, I think. Ten airports in two hours. That’s a personal best. That’s something to work on later.

“Can you imagine what this is going to look like in my logbook?” Justin says.

We taxi and park, tie down the airplane, and head inside. We don’t get five feet inside the building before someone walks by and we’re telling the story. Guess what we just did!

Yes, one of the joys of flying is the story you get to tell, the story of how the sky did or did not open and how every bounce of the wheels is a reason for joy. Ten airports! Ten different airports in two hours. This should be official, I think. There should be certificates and plaques on the wall. But we already have what really matters.

Filling out the paperwork, though, we get one last surprise.

Tach time: 1.7

Hobbs time: Exactly 2.0.

Beat that.

W. Scott OLsen is an English professor at Concordia College in Moorhead, Minnesota.