Fly-outs: A flight through southeast Europe

Sights and flights around Greece

Sipping an impossibly dense and tasty Greek coffee on the restaurant terrace the next day, I understood how a landscape can be quite literally mesmerizing.

Sipping an impossibly dense and tasty Greek coffee on the restaurant terrace the next day, I understood how a landscape can be quite literally mesmerizing.

The sights

Of course, Santorini is no well-kept secret. During the summer months, nonstop flights from seemingly every good-size city in Europe touch down in an endless parade, while the largest cruise ships drop anchor for the day in the 1,300-foot-deep caldera. The shortage of buildable cliffside real estate means that as you walk the three-foot-wide pedestrian “road” from your room to the hotel’s restaurant, the dozen cave-like rooms you pass likely belong to an equal number of other hotels, private owners, and rental companies. Even so, as soon as one steps away from the throngs in the major tourist areas, a hushed serenity quickly descends.

On all fronts Santorini manages to live up to the high bar set by its reputation as everyone’s favorite Greek island. Yes, the Santorini tomatoes really are that good—as is all the food. Yes, the white wine made from the local Assyrtiko grape really is unique, yet delicious and approachable to a Western palate. And in even the hottest part of the day, a constant onshore breeze blowing up the cliffs keeps the temperature comfortable, providing an ideal blend of ridge lift and thermals for the near-stationary sea birds hovering an arm’s reach away. Walking through the towns, everywhere one looks are the blue roofs and whitewashed walls that are synonymous with the island.

The short flight from Santorini to the island of Samos couldn’t provide a larger culture change while remaining in the same country. As relaxed as Santorini is cosmopolitan, Samos is popular with retirees and for multigenerational family vacations. Just past the runway end, a stone’s throw from the ocean, successions of low-slung resorts sit against the sandy beach. A mile down the beach, the postcard-perfect town of Pythagorio (named for the hometown mathematician and bane of many schoolchildren’s geometry lessons) fronts the oldest manmade port in the Mediterranean.

With a day to kill, my wife and I walked the mile up into the hills above the beach, to the Monastery of Panagia Spiliani. Perched at 400 feet elevation above the town, the exterior buildings of the monastery are built around a deep cave sheltering a tiny church dating back to Byzantine times. Descending into the cave—also thought to have been the teaching place of Pythagoras himself—as the temperature plummets and humidity climbs is a hair-raising experience.

With a day to kill, my wife and I walked the mile up into the hills above the beach, to the Monastery of Panagia Spiliani. Perched at 400 feet elevation above the town, the exterior buildings of the monastery are built around a deep cave sheltering a tiny church dating back to Byzantine times. Descending into the cave—also thought to have been the teaching place of Pythagoras himself—as the temperature plummets and humidity climbs is a hair-raising experience.

The layers of history in Greece exist at a scale that overpowers the senses and mind. Around every corner is a site of such significance that, if it were moved to the United States, tour buses by the hundreds would pull up daily. Yet we had the cave to ourselves as two robed monks talked quietly in the shade outside.

Nowhere was this cultural density more apparent than at our last Greek stop—the putative birthplace of western civilization itself, Athens. Trying to endure the 100-degree days Athens was experiencing, my wife and I took a circuitous route to the Acropolis that let us spend a large part of the walk in the shade of a large park. Our path through the park serendipitously dropped us directly across the street from the entrance to the Temple of Olympian Zeus—once, by the way, the largest temple in Greece. Even without purpose one can’t walk through the heart of Athens without stumbling across near-wonders of the ancient world.

The flights

The flying part of our adventure is pure Europe, through and through, mostly in that nothing is predictable. Flying into Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam, Netherlands (EHAM), single-pilot to pick up my friend had necessitated hours of study in the weeks leading up to the trip. Printing the Jeppesen information pages, arrivals, departure, and approaches for EHAM took more than 50 double-sided sheets of paper. The informational pages alone run 16 pages.

Yet, after highlighting arrivals and RNAV transitions and preferred runway pairings and noise abatement proscriptions ad nauseum, the actual arrival process is no different than at any Class B airport in the United Sates: radar vectors from the en route structure right onto the ILS. Likewise, on departure, a last-minute runway and SID change had no practical implication, because we never even hit the first fix on the SID before we were vectored to our first en route fix.

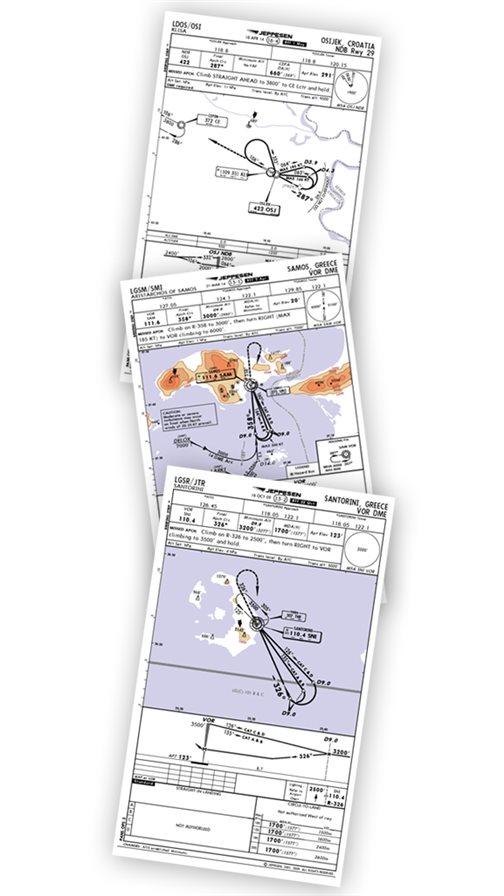

And just as the complex can be rendered simple, so is the reverse true. Approaching Osijek, Croatia (LDOS), after leaving Greece, the marginal VMC conditions had us expecting to fly the ILS 29 procedure. On initial contact with the nonradar Osijek Approach, however, we found that the ILS was out of service (no notam to that effect, of course), and we would be flying the full NDB 29 instead. Looking a bit like fairy wings as drawn by my 6-year-old, the NDB 29 features not one but two course reversals before aligning with the runway, as well as a gentle note not to overshoot the second reversal, as that would put you in Serbia—a country only 20 years before embroiled in war with Croatia.

Despite the procedural change-ups, the mysterious fuel delays, and the occasional missing handlers when arriving at the airport, flying GA through Europe retains an undeniable charm. I’ve yet to partake in a Europe-hopping trip that didn’t leave the pilot smiling—yet all too often, I hear pilots saying “maybe next year” and delay their first self-flown visit.

Despite bureaucrats’ attempts to make it otherwise, with a good handling company on your side, the flexibility of flying directly from the busy island to the quiet, from the capital of one nation to a city of only 100,000 in another, allows for a pace of exploration and adventure perfectly tuned to the pilot’s speed.

Neil Singer is a Master CFI with more than 8,500 hours in 15 years of flying.