California: Higher Education

The Sierra Nevada offers lessons for flatlanders

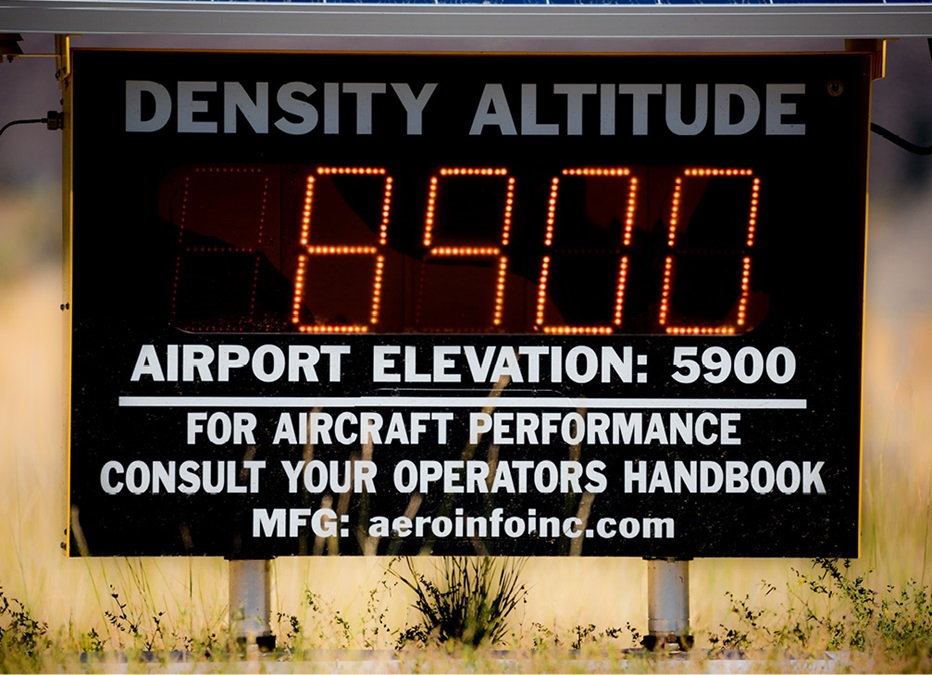

A digital sign displays today’s density altitude: 8,900 feet. Flatland pilots know they’re not in Kansas—or Maryland, or Minnesota—anymore.

The signs offer lighthearted reminders that no one treats lightly—not when the brownish peaks of the Sierra Nevada are visible all around the airport.

Truckee-Tahoe, elevation 5,901 feet, is the base camp for a weekend mountain flying adventure hosted by CFII Jason Miller of The Finer Points of Flying aviation podcast. Miller has shepherded mountain fly-outs since 2011. Pilots flying Cessna 172s and 182s—and a lone Beechcraft Bonanza—have come here to learn the meteorology, geography, and power/performance issues that accompany high density altitude operations. Ken Kolz, Thomas Mangione, and Martin Smith are planning trips to high-elevation airports such as Big Bear and Aspen. Thanos Diacakis and John Ryan have flown in the mountains but want a greater challenge. CFI Miriam MacMillan is here to be trained so that she can give mountain checkouts. Trevor Haworth says a group of friends is coming to visit from the United Kingdom, and they’re keen to fly to the Grand Canyon and Lake Tahoe.

“Someone in the group should have some knowledge,” he jokes.

Heading to Truckee-Tahoe

As pilots and flight instructors assemble in San Carlos, California, Miller catches each one and weighs their luggage. There’ll be no eyeballing weight and balance calculations on this trip.

“The goal is to have you leave here feeling comfortable and confident,” Miller tells the group. Each airplane will have a CFI on board, and the weekend will include a hands-on discussion of survival tactics—and a chance to experience the mountains from the vantage point of a sailplane.

The 147-nautical-mile flight from San Carlos Municipal Airport to Truckee-Tahoe offers a lesson in navigating congested airspace, as pilots must remain clear of San Francisco’s Class Bravo while departing San Carlos. Smoke from wildfires forms a grubby hazy layer on the horizon.

The airplanes fly over the Central Valley, and soon the terrain begins rising to meet them. The pilots have been briefed to fly the Gateway approach to Truckee-Tahoe—keep to the south of Donner Lake to the “Gateway,” a convergence of highways and railroad tracks, and then follow Highway 267 to Runway 29. The airport handles a large volume of light jet and commercial operations, including Pilatus PC–12NGs operated by Surfair; within five miles of the airport, position reports are rapid-fire and precise.

Touching down on Runway 29, the airplanes taxi to a gravel-covered ramp off Runway 20. This is the base of operations for Truckee Tahoe Soaring Association, whose Schweitzer SGS gliders and Piper Pawnee towplanes will be in almost constant use this weekend.

Pattern work

After tents are pitched and sleeping bags unfurled in a pine grove several hundred yards from Runway 20, it’s time to fly. It’s 85 degrees Fahrenheit—a typical August temperature—but as Miller notes, “It takes the hottest part of the day to learn how air density affects engine performance and lift.”

Normally aspirated aircraft won’t operate at full power at this temperature and altitude. The mixture must be leaned for best power or by the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Taxiing onto Runway 20, there’s no rolling onto the centerline and pushing the throttle forward. “Hold the brakes, set the power, then let go of the brakes,” Miller says. “Depending on what [you’re] used to, it’s going to feel pretty anemic.” If you have not reached 70 percent of rotation speed by the halfway point of the runway, abort the takeoff, he says.

With four adults on board, the Cessna 182 meanders down the runway as if in no hurry to get to rotation speed. When it finally does, “The rotation phase of the flight will last longer than at sea level,” Miller says. “You’ll rotate, continue to go down the runway—you may have to reduce pitch—and trust that indicated airspeed.”

The high density altitude causes the engine and prop to produce less thrust, so the climb angle must be flatter. Flatland pilots must not succumb to the habit of pointing the airplane’s nose at a certain angle. “For a hot or cold day, I know my VY will be different,” says CFI Mike Korklan, who is flying with Bonanza owner Mangione. “It makes my workload smaller.”

The pilots struggle with the workloads of an unfamiliar airplane, a right-hand pattern that includes a 270-degree left turn before joining the downwind, an unfamiliar sight picture, and near-constant chatter on the common traffic advisory frequency.

“Keep up that flying speed,” Miller urges as the Cessna 182 approaches the touchdown point. Don’t aim for the beginning of the runway, he advises. If the airplane’s wheels aren’t down by the halfway point, go around. Those are good practices to incorporate in your everyday flying, he adds: “Standardization only earns its weight in gold if it’s used.”

At day’s end, the pilots enjoy a catered dinner, and get to know each other. A mountain checkout graduate has dubbed the weekend “airplane camp for adults,” and that’s an apt description as pilots hunker around a fire pit to share flying stories. Mangione is jubilant: “Just this first day was worth the money,” he says. “I did three touch and goes. It was a real confidence-builder.”

Threading the peaks

With daylight comes the next challenge: It’s time to leave the pattern. The Sierra Nevada’s peaks average 10,500 feet, although Mount Whitney reaches to 14,500. If your airplane’s service ceiling can’t match that, you must navigate around the peaks instead of over them. The airplanes depart for Bishop Airport (elevation 4,124 feet) and take varying routes through the passes.

The Cessna 182 circles Lake Tahoe as pilot in command Martin Smith files and opens a flight plan with Reno Radio. Adventurer Steve Fossett disappeared in September 2007 while flying a Decathlon in the Sierra Nevada. The crash site wasn’t discovered until September 2008. Fossett didn’t file a flight plan.

Miller likens the topography to fence posts—a forest of jagged peaks ranging 70 miles east to west and more than 400 miles north to south.

Now picture the air currents moving over those fence posts as water. “If the water hits the rocks, it goes up on the front side of the rock, and down the back side of the rock. It accelerates over the top, and somewhere downstream it becomes a turbulent eddy,” Miller says. Anticipating how air currents will move over the mountains helps you navigate safely between them, he explains. Expect updrafts near a ridgeline where the wind is blowing over it, and downdrafts if approaching it from the other side.

Miller instructs Smith to cross an approaching ridgeline at a 45-degree angle. This permits the pilot to maneuver to lower terrain if necessary without having to do a 180-degree turn.

Knowing when to draw a line in the sand and stay on the ground will help keep you safe, Miller says. Winds blowing 30 knots at the surface could translate to 55 knots at the ridgeline altitude—and that’s not where you want to be in a light aircraft.

Bumps and bounces

The return trip from Bishop to Truckee-Tahoe is bouncy, thanks to thermals of warm air that delight glider pilots but make it tough going for the 182’s backseat passengers. The bumps are bothersome but they’re not convective; no clouds are in evidence. Clouds hovering at ridge levels may signal impending thunderstorms.

As the 182 navigates Buckeye Pass, Miller points to first one, then another postage-stamp-sized bit of ground that could be an emergency landing site. To the untrained eye, these patches of ground don’t look promising, but CFI Sarah Halas says the range is more survivable in an engine-out situation than the Teton Range of the Rocky Mountains, which has violent weather systems (see “Survival Strategies,” page 57).

The scenery from the vantage point of a Cessna 182 prompts a rush of awe, respect—and, yes, a little relief when wheels touch down again at Truckee-Tahoe. You’ll never capture views like these from the window seat of a commercial flight.

Glider flights and more pattern work cap off the weekend. After a “brutal” day of performing canyon turns, slow flight over Lake Tahoe, and touch and goes at a 4,800-foot-elevation airstrip, Mangione says he now feels comfortable about plans to fly his Bonanza from his home in Riverside, California, on a family trip to Mammoth Lakes, California—elevation 7,000 feet. “I texted my wife and said, ‘Yeah, we’re flying,’” he said.

Diacakis learned to fly in Colorado, but he said that was “mostly how to get from A to B and avoid the tall peaks in between.” Flying in the Sierra Nevada “was great to get more comfortable with the terrain and how to navigate it at a slightly lower altitude, and it was great to get hands-on advice from the experienced instructors.

“I am much more likely to bring the family with the plane up on trips to Tahoe,” he said.

Email [email protected]

Survival strategies

Survival strategies