On Instruments: Making the miss

Details on a tense procedure

Fly long enough, and this will happen to you: You’re flying in the soup. Your destination’s TAF was inaccurate, ceilings and visibilities are down, better weather is nowhere nearby, and you’re faced with shooting an approach to minimums. You’d better be ready to fly the best approach you can—and be well-prepared to perform a missed approach procedure.

Too many of us don’t practice missed approaches often enough. So when your number comes up, so does the stress.

Preparing for the miss

Preparing for a missed approach starts long before reaching the approach’s initial approach fix (IAF). In fact, it should start before you even take off, by studying the destination—and alternate—airport’s published approaches. Pay special attention to chart notes and notams. You don’t want to find out at the last minute that approaches aren’t authorized at night, for example, or that certain approaches are out of service, or decommissioned altogether.

With early, non-WAAS (Wide Area Augmentation System) GPS units you must perform a preflight check of receiver autonomous integrity monitoring (RAIM) to check for satellite integrity and availability. WAAS GPS preflights are simpler. If WAAS notams indicate any GPS outages affecting your flight, then you must do the preflight RAIM check. If there are no outages or other satellite problems, a WAAS GPS receiver will do its own GPS signal checks in flight.

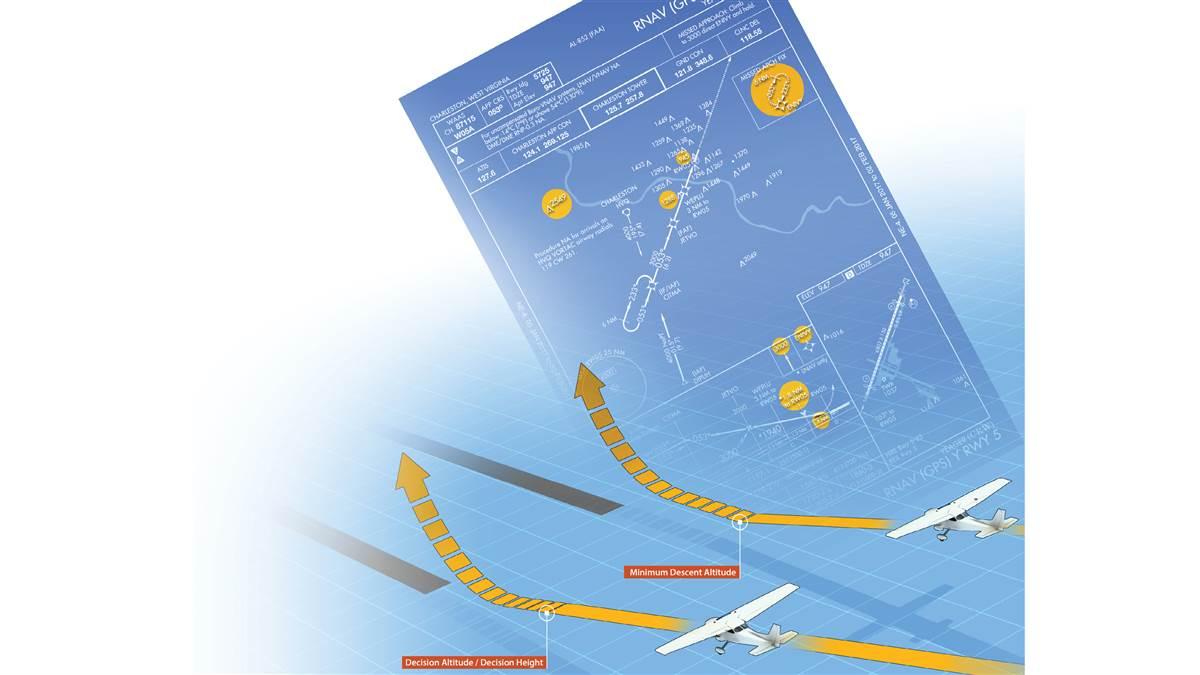

En route, you should brief the upcoming approaches by going from the top of the approach chart to the bottom, taking in every bit of information. By the time you arrive at the IAF, or begin receiving any vectors for the approach, you should have copied down the airport’s surface weather from AWOS or ATIS broadcasts. Now you know how likely a missed approach may be. Another review of the approach procedure is in order, with special attention to the inbound courses, minimum crossing altitudes for fixes along the way, decision heights (DH), decision altitudes (DA), and minimum descent altitudes (MDA).

Even if the weather isn’t at minimums, a thorough study of the missed approach procedure is a must. At the very least, memorize the first two steps. There won’t be any time to pull out a chart and read the procedures when you’re flying the miss.

GPS quirks

Instrument landing system (ILS), VOR, and other such VHF-based approaches generally follow the same protocols. After becoming established on the final approach course, it’s a matter of tracking it while descending to the decision altitude (the height above mean sea level), decision height (the height above the runway threshold), or minimum descent altitude—all the while keeping an eye on your time to the missed approach point (MAP). If conditions call for a missed approach, the pilot hand-flies the procedure using the published instructions. But GPS avionics differ in the way they give guidance upon reaching the MAP. It can vary from manufacturer to manufacturer, from one model to another, and even according to the software version in use.

For example, some older GPS navigators require that you press a key that will suspend navigation guidance after passing the missed approach point; then you must hand-fly the airplane until established on a leg of the MAP, and then reengage the navigation function as you fly through the rest of the missed approach procedure. That’s a lot of button pushing and course dialing at a very busy time.

Newer, WAAS-enabled GPS units often give a prompt on the display screen, asking if you want to activate the missed approach. If so, press the appropriate touchscreen button and you’ll be given automatically sequenced course guidance through the missed approach procedure. Some newer WAAS GPS software versions let you activate a flight director’s command bars for the initial missed approach climb, so there’s no need to push buttons. This lets you use an autopilot with GPS Steering (GPSS) to fly the full missed approach procedure—missed approach holding pattern included.

It’s impossible in this short space to give specific instructions on legacy and WAAS-enabled GPS panel set-ups because of the variety of navigation receivers and navaids (GPS and otherwise). Here’s where quality instruction with a savvy instructor can provide you with the details relevant to the navaids you’ll be flying. Hitting the books is another great idea. Not too long ago, flying electronically guided instrument approaches meant using one of a mere three types of navaid schemes. Today, that number is up to nine.

Decision time

When and where is the MAP? With ILS approaches it occurs when you arrive at the published DA. But don’t hang your hat on this. If your glideslope needle flags out—it’s rare, but it does happen—you cannot legally descend to DA. Instead, the approach becomes a localizer approach, and higher minimums apply. Now where’s the MAP? Answer: when the time between the FAF and MAP elapses. This is when you’ll be glad you timed your approach. Besides, timing your way down the final approach course is a good habit to cultivate.

Unless the MAP is defined by, say, a navaid on the airport, then your elapsed time from the FAF marks the MAP for nonprecision approaches. This timing assumes a constant descent rate and a constant groundspeed—not indicated airspeed. If you encounter unexpectedly strong headwinds on final, your elapsed time may put you short of the runway threshold instead of at the published MAP. Now you may have cheated yourself out of a good look at the runway environment if visibility minimums are typical—one mile. Conversely, a tailwind on final may put your new MAP right over—or even past—the airport. If you catch a glimpse of the runway, there’s the temptation to do a dive at it, and end up landing dangerously fast and long.

With RNAV GPS approaches, the MAP depends on the type of approach. Localizer performance with vertical guidance (LPV) approaches—while technically nonprecision approaches—still give vertical guidance, and typically have DA minimums of 250 feet and visibility minimums of one mile. But there’s a catch. Although the DA is published on approach plates, the point at which you arrive there isn’t. This means you can’t wait for the GPS to count down to zero to identify the MAP—because with LPV approaches the mileage countdown ends at the runway threshold. Wait for zero and you’ll be at 250 feet agl over the runway threshold. Use the DA minimum as the MAP, as with ILS approaches.

Flying the miss

Let’s say you’ve arrived at the MAP and see nothing. The decision is easy: Perform the missed approach procedure. This means applying power immediately, pitching up to a climb attitude and airspeed, and retracting gear and flaps during the climbout.

With nonprecision approaches, no loss of altitude is permitted during the transition to the climb. ILS and LPV approaches are more forgiving. During the transition from the MAP to the missed approach climb, dipping slightly below the DA or DH is allowed. That’s because the rules take into account that the airplane could be in a descent to the runway when visibility is lost.

Unless obstacles, terrain, or other issues are factors, your initial track will most likely be straight ahead. You’ve remembered the first two steps of the missed approach procedure, so you’re free to concentrate on flying—and climbing. Whatever you do, don’t freeze and bore on at high power and low altitude; obstacles and terrain could be ahead. And don’t turn back to the airport if you spot a path through clouds. This is a deadly temptation to bank around clouds at low altitude. This not only invites disorientation or a stall, it may put you back in the clouds without any guidance to the airport or runway.

Many pilots flying GPS-based approaches fixate on taking the GPS navigator out of suspend mode (by pressing the “OBS” button on early Garmin 530/430 navigators, for example) as soon as the airplane is climbing away from the MAP. This can be a trap, because if the missed approach instructions call, say, for a climbing turn to 3,000 feet and you unsuspend the GPS as you pass through 1,500 feet, the unit will calculate a straight-line course to the next waypoint in the missed approach procedure. Trouble is, if you follow that course you might hit a 2,000-foot-high obstacle along the way.

Two other missed approach traps are worth mentioning. One involves LPV approaches where the WAAS GPS receiver detects a signal degradation either 60 seconds before your arrival at the final approach fix—where a signal test is automatically performed as a routine matter—or during the descent on the final approach course. When this happens, you’ll know it. You’ll see an “approach downgraded—use LNAV minima” message on your display. Now the LPV minimums are out the window, and you are limited to descents to LNAV minimums. If you lose a signal completely, you’ll get an “abort approach—navigation lost” message. That means an immediate missed approach procedure, unless you have a second WAAS GPS receiver as a backup—ready and programmed for the approach.

Finally, there are dangers when flying LNAV+V approaches. LNAV+V isn’t an official approach type, so you won’t see them on any approach plate. However, they do provide ILS-like lateral and vertical guidance cues. This nonprecision LNAV approach uses a pseudo glideslope for advisory purposes. The pseudo glideslope will take you to the runway threshold, but avoid using it in actual instrument weather. You won’t see any step-down fixes on final, and you must observe LNAV MDAs. The most dangerous aspect would be continuing the approach below the MDA, losing sight of the runway, and having to perform a missed approach. Because you are now below the legal MAP, any turns you make can put obstacles or terrain in your path. That’s because you may be well beneath any LNAV missed approach altitudes.

GPS approaches and missed approaches are weighty subjects, and this article addresses a partial list of the information you need to know. For a more thorough treatment, consult the FAA’s Instrument Procedures Handbook (FAA-H-8083-16A) and Max Trescott’s excellent GPS and WAAS Instrument Flying Handbook.

Email [email protected]