Weather: Out Front

Norwegian cyclone model makes sense of weather events

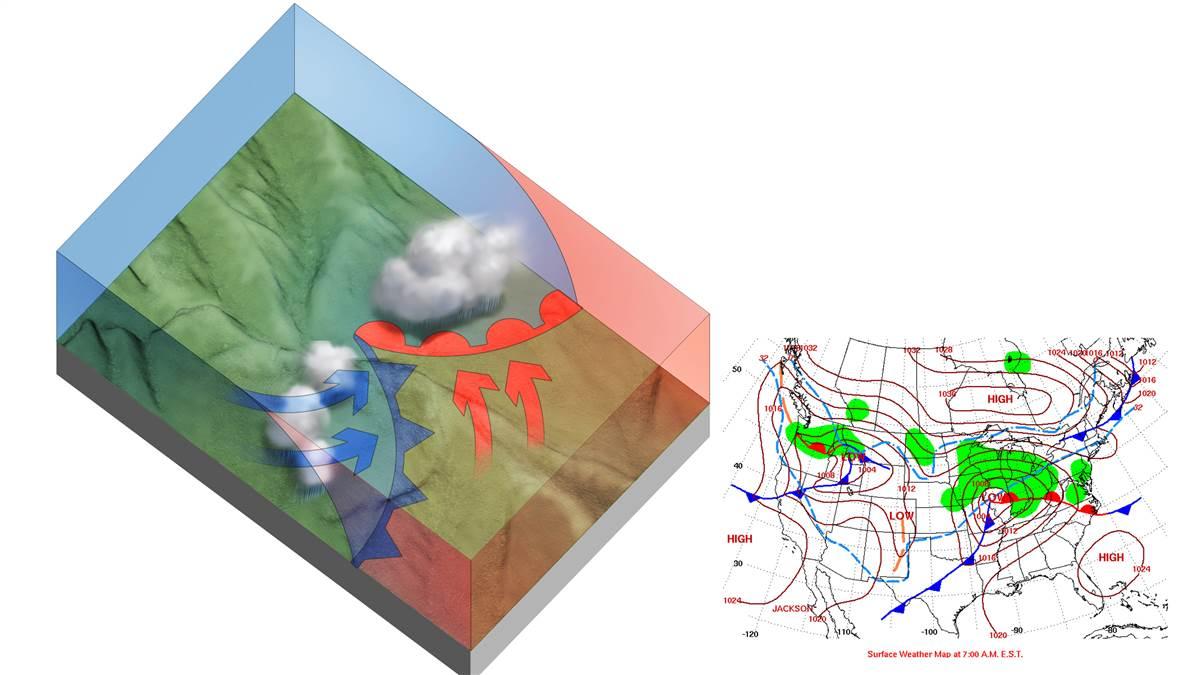

Illustration by Charles Floyd

Weather forecasts sometimes sound like reports from a war—with fronts advancing, or cold or warm air invading some place or another, creating poor flying conditions.

The military terminology originates with World War I, when battles along the Western Front were in the news as meteorologists in neutral Norway were working out the picture of masses of warm and cold air advancing and retreating behind what they called “weather fronts.” This “Norwegian model” helps us make sense of complex weather events that would otherwise be hard to understand.

Interactions between masses of warm and cold air create large extratropical cyclones that move generally west to east as cold air moves toward the south and east, and warm air toward the north, revolving around a low-pressure center. The National Hurricane Center defines extratropical cyclones as cyclones for which the primary energy source is baroclinic—that is, results from the temperature contrast between warm and cold air masses. Some of these storms can bring snow, ice, or rain to almost all the contiguous 48 states, ranging from blizzards in the north to strong thunderstorms across the south.

Broadcast meteorologists usually use maps showing areas of high and low pressure, and fronts, to help explain their forecasts. If you know what happens along the different kinds of fronts and behind them, you’ll have a better idea of what kind of weather to expect.