Savvy Maintenance

Opinion: Grand theft propeller?

Can a mechanic hold a part hostage?

The mechanic who phoned me sounded agitated. He explained he’d been an A&P for quite a while, but had earned his inspection authorization relatively recently. An owner had brought a 1950s-vintage Piper PA–22 Tri-Pacer to him for an annual inspection. During the inspection, the IA discovered the aircraft’s metal, two-blade, fixed-pitch Sensenich propeller was severely corroded. The prop was so badly corroded that not only did the IA consider it unairworthy, but he seriously doubted it was repairable. Consequently, he advised the owner of the Tri-Pacer that the airplane needed a new prop.

The owner was not happy about the IA’s verdict and initially resisted his recommendation, but he reluctantly agreed to pay for a new propeller and told the IA he wanted the old propeller back. When the IA inquired why, the owner indicated he was planning to list the old prop on eBay in hopes of getting some money for it to help defray the cost of the new propeller.

The IA was horrified. “You can’t do that,” he told the owner. “What if someone put that horribly unairworthy propeller on an airplane and it failed and caused an accident?” The dispute over the corroded propeller escalated. The owner demanded the old propeller and the IA refused to release it. On the recommendation of a colleague, the IA had called me for advice.

Whose prop is it?

I waited until the IA had finished relating his tale of woe. Then I unloaded.

“You’re refusing to give the man his prop back?” I asked rhetorically, mustering my best I-don’t-believe-what-I’m-hearing tone of voice. “What are you thinking? It’s not your prop, it’s his prop! If you don’t give it back to him, he could file a police complaint against you for theft. Give the man his prop back!”

“But he says he’s going to put the prop up for sale on eBay!” the IA protested. “What if someone buys it, puts it on an airplane, and the plane crashes? What if that happens and the authorities trace the bad prop back to the owner and then back to me? I could get into a heap of trouble!”

But the owner hired the IA to perform an annual inspection on his Tri-Pacer. The IA’s regulatory responsibility is to make a professional airworthiness determination of that aircraft, and he did that. He determined the aircraft was unairworthy because of the corroded prop, and the prop needed to be replaced. The owner agreed to replace the prop, so the IA’s job was over. “Give the man an invoice and as soon as he pays it, give him back his airplane and his old prop,” I said.

It was the IA’s responsibility to determine the propeller was unairworthy. It was the owner’s responsibility decide what to do about that.What the owner does with his bad prop is not the IA’s responsibility. The IA can recommend to the owner that if he lists the prop for sale on eBay, he represents it as being in unserviceable condition. But it’s the owner’s prop and he can do whatever he wants with it.

Suppose the owner had refused to replace the corroded prop on his Tri-Pacer. The IA would have signed off the annual as unairworthy and given the owner a signed and dated discrepancy list stating the propeller was unairworthy because of corrosion. Then he would have released the Tri-Pacer back to him, corroded prop and all. The IA couldn’t force the owner to replace the propeller, and once the owner paid the invoice the IA would have no authority to hold the airplane.

Personally, I would have no problem with the owner putting the prop up for sale on eBay so long as he described its condition accurately in his ad and included a photo showing its condition. Maybe someone would buy it and hang it on the wall. If the owner’s eBay ad represented the prop as being airworthy, he might possibly be in violation of FAR 3.5 (Statements about Products, Parts, Appliances and Materials), but I’ve never heard of the FAA bringing an enforcement action against an individual aircraft owner for violating FAR 3.5. The mechanic could not get in trouble for giving the owner his prop back, but he could get in big trouble by refusing to do so.

Owner and mechanic responsibilities

The FARs provide clear guidance regarding owner and mechanic responsibilities for maintenance. Owner responsibilities are set forth in Part 91, Subpart E (the 91.4xx rules), while mechanic responsibilities are set forth in Part 43 and Part 65, Subpart D (notably 65.8x for A&Ps and 65.9x for IAs).

As a general proposition, the FARs place the responsibility for what maintenance is done and when it is done on the aircraft owner, and the responsibility for how the maintenance is done on the mechanic. When it comes to airworthiness, FAR 91.409 (Inspections) requires an aircraft owner to have his aircraft inspected and an airworthiness determination made by an IA once a year. During the remaining 364 days of the year, it is the responsibility of the pilot in command to determine airworthiness (FAR 91.7, Civil Aircraft Airworthiness).

Many aircraft owners do not own up to their full regulatory responsibilities regarding maintenance, and they frequently abdicate many of those responsibilities to their mechanics. Many mechanics also take on responsibilities that properly belong to their aircraft-owner clients, and in doing so expose themselves to liability that they shouldn’t be exposed to.

In the case of the Tri-Pacer, it was the IA’s responsibility to inspect the aircraft and to make a regulatory determination that the corroded propeller was unairworthy. It was the owner’s responsibility decide what, if anything, to do about that.

The owner might have tried to find some other mechanic to inspect the propeller and declare it airworthy. He might have elected to send the prop to an FAA-approved propeller repair station for repair. Or he might have elected to do what he did: replace the prop with an airworthy one. All that would have fallen into the what category for which the owner is responsible, not the how category for which the mechanic is responsible. The owner could ask the mechanic for help in determining his options, but the decision is the owner’s to make.

Who can ground an aircraft?

FAR 91.7 forbids a PIC from flying an aircraft that is unairworthy, although FAR 21.197 (Special Flight Permits) allows the FAA to grant special dispensation to fly an unairworthy aircraft (usually for repositioning purposes). There is no FAR that empowers a mechanic to ground an aircraft. Mechanics are not the safety police.

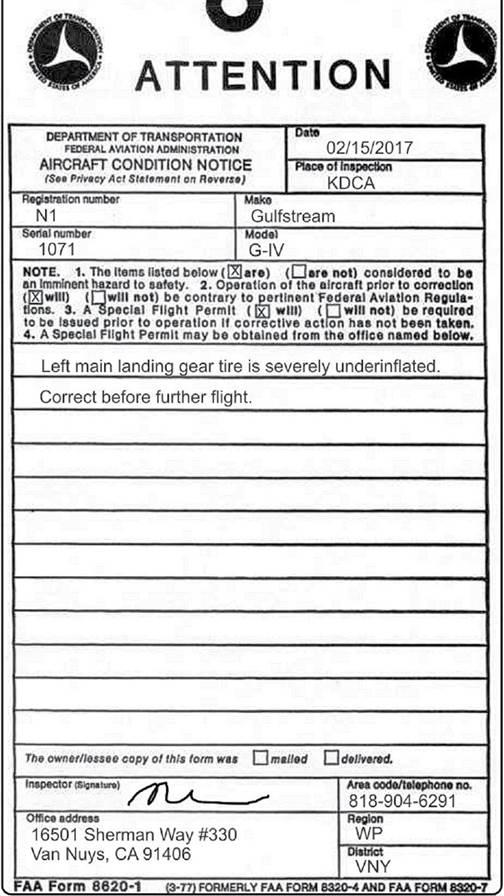

Airworthiness safety inspectors (ASIs) work at the FAA’s 80 flight standards field offices (formerly known as FSDOs), and they are the safety police. An ASI has the authority to ramp check an aircraft and hang an Aircraft Condition Notice (Form 8620-1) on it requiring that a specific unsafe condition be corrected before further flight. An A&P has no such authority.

A vindictive mechanic who wants to prevent an aircraft-owner client from flying his aircraft could conceivably call an ASI and try to persuade him to come out to inspect the aircraft. I think that’s poor form, to say the least. It’s like calling the cops to complain that your neighbor is playing his stereo too loud, instead of calling the neighbor and asking him nicely to turn down the volume. In my view, a mechanic who “calls the cops” on one of his clients (except in the most extraordinary circumstances) should be avoided.

Mike Busch is an A&P/IA. Email [email protected]

Webb: www.savvyaviation.com

An aviation safety inspector can issue an aircraft condition notice requiring an unsafe condition to be corrected before further flight.

An aviation safety inspector can issue an aircraft condition notice requiring an unsafe condition to be corrected before further flight.