A Phenom evolves

The Phenom 100EV conquers hot and high

Take the case of Craig Kellerstrass, CEO and president of the Kellerstrass Oil Company of Ogden, Utah. The company, founded in 1948, is a diversified enterprise with interests in retail gas stations, trucking, hauling fuel and lubricants, mining, and construction. Although based in Ogden, the Kellerstrass organization has offices at sites scattered across Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, Montana, and Idaho. “For years I put a lot of miles on cars, driving from location to location,” Kellerstrass said. “Then I got my pilot certificate and bought a brand-new Cessna 182 in 1998, followed by a Turbo 206 with a Garmin G1000 in 2005.”

But as the business grew, so did the travel. “And as we started carrying more passengers to more locations, we found those Cessnas were no good in the winter, what with all the icing, and in the summer we’d have issues with hot-and-high takeoff and climb performance in all that mountainous terrain,” he said. “It got so that we couldn’t fly if the temperature was above 85 degrees,” citing airports at Moab, Utah (elevation 4,557 feet msl) or Monticello, Utah (elevation 6,966 feet msl) as examples. Other destinations in California, Texas, and Illinois took too long to reach, and made for uncomfortable trips with four to six passengers.

So in 2010 Kellerstrass made the jump to a jet. After checking out the Cessna Mustang, CJ1+, and Pilatus PC–12NG, he sprang for a new Embraer Phenom 100. That gave him the performance and range the company needed, and it didn’t hurt that the airplane came with Embraer’s Prodigy avionics suite—which is essentially a Garmin G3000 panel optimized for the Phenom. His equipment leasing company owned and flew the Phenom for 1,000 hours, and even dry-leased it back to other Odgen companies.

When Embraer announced the Phenom 100EV, the second upgrade of the original Phenom 100 design, the company placed an order immediately. By March 31, 2017, Kellerstrass took delivery of the very first Phenom 100EV.

Panel and performance

The 100EV brings several enhancements over its immediate predecessors, the Phenoms 100 and 100E. One was a tweak of the Pratt & Whitney PW617F-E engines that upped thrust to 1,730 pounds per side—a total of 70 additional pounds over the earlier models’ 1,695-pound-per-side ratings. Maximum takeoff weight was raised by 121 pounds, to 10,703 pounds; nominal maximum payloads were boosted by 44 pounds; and so was full-fuel payload.

This hike in thrust (a total of 15 percent, Embraer says) and load translates into benefits in hot-and-high operations. Because earlier Phenom 100s were sometimes weight limited for high-density-altitude takeoffs, pilots would have to decide whether to restrict fuel or passenger loads. With the EV’s extra thrust these tradeoffs aren’t compromised as much. Then there’s the faster maximum cruise speed: 406 knots for the EV, versus 389 knots for the 100 and 100E.

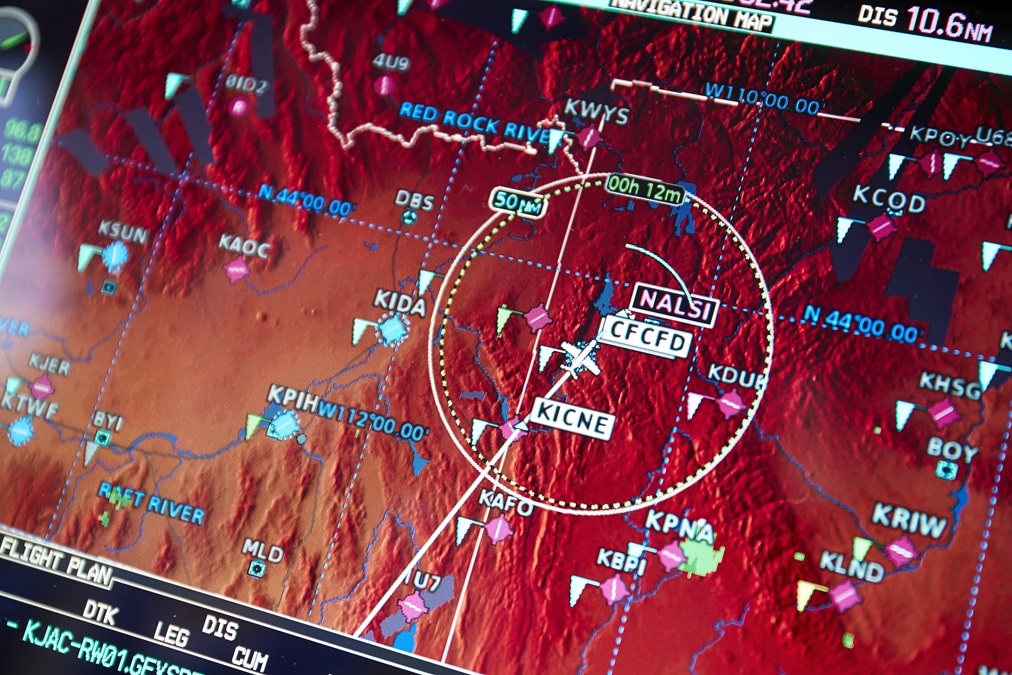

A hike in thrust and load translates into benefits in hot-and-high operations. Then there’s the faster maximum cruise speed: 406 knots. The EV’s new Prodigy Touch avionics suite is another draw. This Garmin G3000-based installation comes with brighter, higher-resolution, 14-inch diagonal display screens that can each be split into two-view setups, allowing a total of six different screenviews. Also included are dual touchscreen controllers that interface with the panel-mount displays, as well as providing their own functionalities—such as tuning nav/com radios, calling up V-speeds, or running checklists.

With the EV comes an improved brake control unit and the ninth software iteration of the brake-by-wire system. Earlier brake systems were famously grabby, as they were designed for a single purpose: maximum braking. It was either no braking or, once pedal travel reached a critical point, maximum braking. The result was that pilots would attempt to soften this harsh deceleration by pumping the brakes. This only made the problem worse, as the system would reset for maximum braking each time the pilot released brake pressure.

This, in turn, could cause longer landing distances, which have been implicated in several overrun accidents. As the system has been refined over the years, newer software lets pilots modulate brake pressures and gives passengers smoother, less-dramatic post-landing experiences.

“We couldn’t climb this fast and at this rate of climb in the Phenom 100. And with this fuel and passenger load, we can fly all the way to Santa Ana, California, nonstop.” —Ryan FarnsworthThe 100E and 100EV’s multifunction spoilers also have helped the airplane slow down more gracefully, both in the air and on the ground. Above 180 KIAS, the spoilers can be used both to help “slow down and go down” and, after landing, with weight on wheels, to automatically deploy for better braking and traction on wet or contaminated runways.

A short hop

AOPA Pilot visited Kellerstrass at his home field, the Ogden-Hinckley Airport (elevation 4,472 feet) in Ogden, Utah, to see his new 100EV—the first in the United States at the time. It was factory fresh, smelled new, and had all of 13 hours on it. It has a two-plus-six-seat interior, thanks to the side-facing forward seat and belted potty. Three of the cabin seats are fully articulating; all have stowable armrests; the dropped aisle is wider than in the 100 and 100E; and the lavatory now has hard pocket doors for better privacy and cabin noise reduction.

Kellerstrass’ chief pilot, Ryan Farnsworth, soon had six of us aboard the airplane for a trip to the Jackson Hole, Wyoming, Airport, 161 nautical miles away. The airplane weighed 10,354 pounds, of which 2,000 pounds was fuel, and on the 70-degree-Fahrenheit day our takeoff numbers were a V1 of 108 knots, a VR of 109, a V2 of 112, and a VFS (final segment climb) of 129 knots. Even some 400 pounds shy of maximum takeoff weight we quickly accelerated into a 220-knot, 2,000-feet-per-minute climb, on our way to FL250—which we reached in eight minutes.

“We couldn’t climb this fast and at this rate of climb in the Phenom 100,” he remarked. “And with this fuel and passenger load, we can fly all the way to Santa Ana, California, nonstop.”

We cruised for 24 minutes, burning 566 pounds per hour (about 84 gallons per hour) per side. For a longer trip, it would make more sense to fly at the 100EV’s ceiling of FL410, where fuel burns are lower and true airspeeds are higher.

Soon after cruising over the pictuesque mountains below, we made a descent into Jackson Hole, using the spoilers for a 3,000-fpm descent to drop into the valley. Then it was a landing at a VREF of 105 knots and a quick turn for the hop back to Ogden, which took all of 34 minutes.

“This would have been a five-and-a-half hour drive,” Kellerstrass said. He ought to know. In his road-warrior days he made plenty of lengthy trips through the mountains. Not anymore.

Email [email protected]