Never Again: The eyes have it

No substitute for a visual check

By Jerry Hawkins

It was a routine morning in June 2001, in the “flyover state” of Oklahoma. I refer to it this way because I had made my living for more than a decade literally flying over the state—more specifically, flying over the interstates, highways, and byways every morning and afternoon as an airborne breaking news and rush hour traffic reporter, with more than 750 flight hours per year.

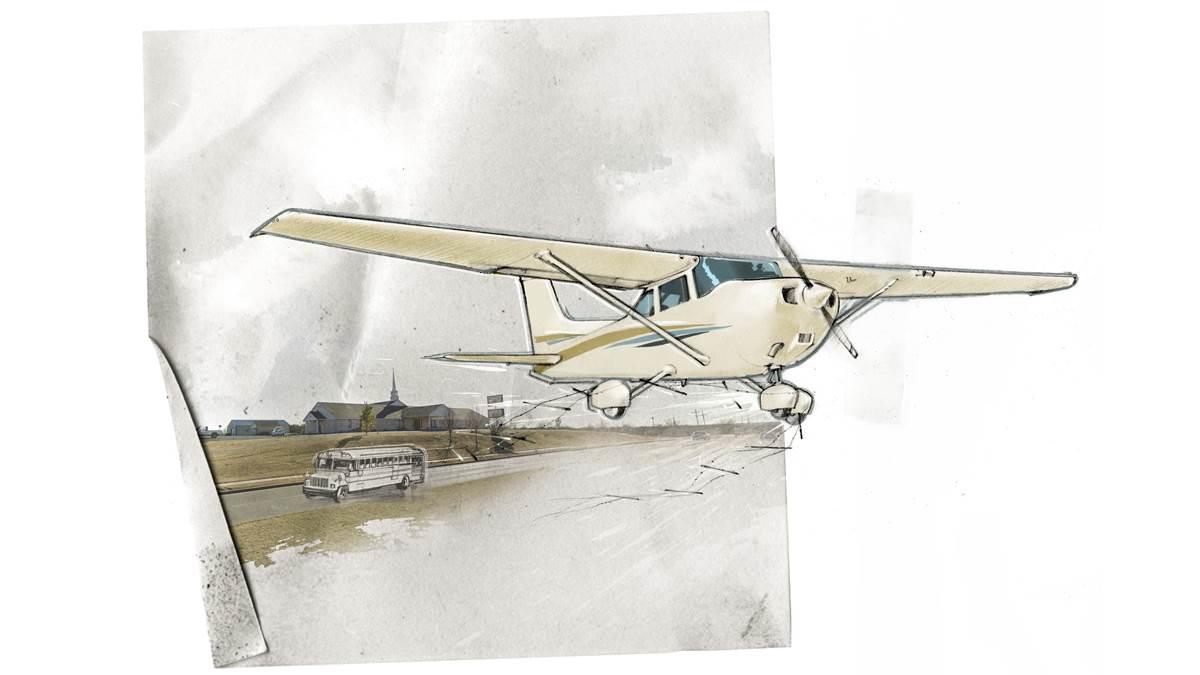

In our business, the routine is etched in what we call the format clock. Pull onto the ramp at 6:30 a.m., jump into the 1982 Cessna Skyhawk the line crew has already fueled and serviced, do a quick oil and fuel check, contact ground for your taxi clearance, then tower for takeoff, and throttle forward to blast off the runway by 6:50 for the first of 39 airborne reports covering four radio stations and one television station. This part usually goes very smoothly, with the use of the prearranged discrete transponder code issued by the Tulsa Tracon—in this case 0-3-6-7 for Skywatch One.

The previous Friday there was a newly trained line crew on duty when I taxied in after the afternoon shift. They were, in retrospect, not yet trained on the procedures we had established—particularly the one regarding the refueling of the aircraft. Unbeknownst to me, the Skyhawk entered its long weekend stay in the hangar with next to no fuel in either of its wing tanks. Fast forward to Monday morning, when the same line crew was on duty, and I happened to oversleep. Because I was running late I raced to the aircraft, thanked the crew for pulling it out of the hangar, jumped into the cockpit, turned the key, and began the morning routine.

Exactly one hour into my three-hour flight, I learned what it felt like to lose an engine and heard nothing but the summer breeze noodling past the cracks in my aging pilot’s-side rubber window seals. My fuel gauges showed that I had a quarter of a tank remaining in both wings. Yet I was staring at a stationary propeller at 2,000 feet msl. How could this be?

I established best glide speed while turning to the nearest suitable landing area. This I happened to know instinctively, only because I had amassed so many hours in this airspace. It was a small, nontowered airport four nautical miles to my north called Harvey Young.

Once established at 65 knots and on a northerly heading, I called the Tracon to declare an emergency, and to let them know that I’d be off-frequency for an indeterminate amount of time. Aviate, navigate, communicate, right?

I continued toward Harvey Young, which started to look like much less than a 50/50 makeable proposition, given my rapidly deteriorating altitude. Around 600 feet agl, I had eliminated any hope of a suitable landing area to the left or to the right, with houses and trees everywhere. I was committed to the straight-in approach for now, and I’d figure out the landing later. As I glided through 300 feet agl, though, a Baptist church with a huge steeple stood at what seemed like a hundred feet to the right of my extended centerline on short final.

Worse, just ahead of the church on the southern perimeter of the field was 21st Street. As I cleared the church steeple, a school bus came barreling down 21st Street from my right to my left, and in my direct line for the runway. I calculated that I could avoid the steeple and miss the school bus, barely, and continue toward the field. No sooner did I make this decision than two other problems presented themselves.

First, I realized I wouldn’t come close to making the runway at Harvey Young, as its threshold was set in about 300 yards from the southern field boundary. The other problem was the perimeter fence, now looming large in my windshield, was made of posts and barbed wire—and lots of it. I knew that I had insufficient altitude to clear the top row of barbed wire as I prepared to make a soft-field landing in the dewy grass ahead. No sooner did that thought hit me when boom! The top two rows of barbed wire wrapped around the fixed gear on my Skyhawk, and I braced for impact.

Somehow, to my amazement, I had just enough forward momentum that I continued my final 10 feet of descent to the ground in what was ultimately a safe, soft-field landing. At this moment I realized that in my concentration to aviate, navigate, and communicate, I had accomplished all except the last item—which was to communicate to my producer back at the radio station that I was in trouble and would be unavailable to provide reports for a while.

At that instant, I heard the words through my FM headset monitor, “And now with a quick airborne check of Tulsa traffic high overhead, here’s our very own ‘Hawkeye In The Sky!’”

My knees were knocking so hard from the stress of what had just transpired that I could hardly think. So I did what any trouper in this business does after realizing all his limbs are still intact—I keyed the mic for the radio station and launched into a regular old traffic report. Only there was nothing at all routine about this one: quivering voice amid gasps of air, some traffic incidents that may or may not have been active when my engine was still purring along….

Perhaps the ultimate self-imposed indignity came after about a 10-minute decompression period. As the dust settled and my heart rate dropped below 200 bpm, my brain woke up and reminded me that the Skyhawk is a gravity-fed fuel system. There’s a primer knob down on the pilot’s left-hand side that spills fuel directly into the carburetor by simply pulling it out and pushing it back in again. Utilizing this technique, I turned the ignition key and the engine quickly roared to life. A simple pull and push of this same knob while airborne 10 minutes earlier might have provided enough power to make the runway after my engine quit.

Lessons learned? The main one is that the eyes have it. As flight instructors preach incessantly, always perform a visual inspection of the oil in your crankcase and the fuel in your tanks. Climb up on the wing and peer down inside—and do this every time you preflight your aircraft. Do not trust your fuel gauges when you have your eyes to trust instead. And don’t let “get-there-itis” prevent you from allowing your eyes to do their job.

Jerry Hawkins is a veteran airborne news and traffic reporter and advanced aviation ground instructor.

Digital Extra: Hear this and other original “Never Again” stories as podcasts every month on iTunes and download audio files free.