Never Again: When to fold ’em

Night flight into thunderstorm

By Donald Burkley

In the 1988 song The Gambler, Kenny Rogers sang, “You’ve got to know when to hold ’em, know when to fold ’em, know when to walk away, and know when to run.” That is pretty good advice for pilots. All pilots are trained and evaluated on problem solving: fuel endurance, performance, weight and balance, systems malfunctions, and lots of emergencies, to name a few. Preflight decisions also are important and should not be taken lightly. Sometimes the best action is to remain on the ground.

In 1990, I was selected for active duty in the Army National Guard to fly a new medium cargo aircraft based on the Short 360. These airplanes are unpressurized, twin-turboprop, 30-passenger, 25,000-pound regional airliners. The military modified version of the Short was called the C–23 Sherpa and was used for many things. In 1991, my unit was based at Aberdeen, Maryland, near the then-Baltimore/Washington International Airport.

One summer day we were assigned to relocate our airplane from Aberdeen to Plattsburgh Air Force Base in upstate New York. Because of scheduled maintenance, our departure was delayed until the early evening. The airplane was released from maintenance on schedule, inspected, and necessary paperwork signed off. The only problem remaining was the disabled condition of the on-board weather radar system. According to the minimum equipment list, the airplane was legal for IFR dispatch without the weather radar, provided a Stormscope is installed and operational. Without radar, precipitation return information would be unavailable. Only convective electrical activity would be seen with the Stormscope. Our aircraft had such an instrument and it was operational.

It is common for summer weather in the Chesapeake Bay area to include isolated thunderstorms in the evening. Our weather briefings by flight service and military sources indicated isolated small thunderstorms around the Baltimore area, diminishing as our proposed track continued to the northeast. Since the cells were not along our route and reported to be small, the decision was made to launch the aircraft as scheduled and briefed. We filed our instrument flight plan knowing Baltimore Radar would keep us clear of any weather. Like all pilots, we wanted to be dependable and complete the mission, and we were confident in our decision.

It was a dark, overcast night when we accelerated down the runway passing V1 and VR. After takeoff and during the initial climb, Baltimore Radar identified us but surprised us with a northwest heading. Radio traffic on the frequency was extremely busy for a Friday night, and we surmised we were being sent off course temporarily because of inbound traffic stacking up because of the weather.

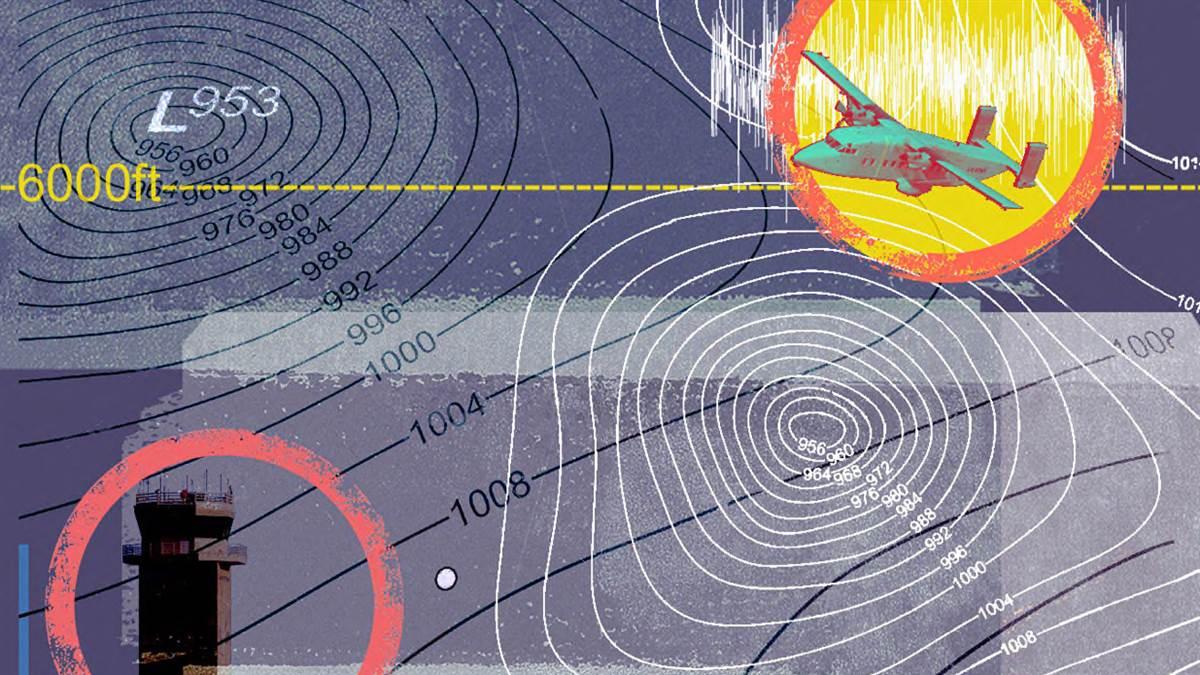

Leveling at an assigned initial altitude of 6,000 feet, we were told to maintain the northwest heading for a few more minutes because of traffic and could expect an on-course turn soon. It was night IMC, and we began to experience rain with light turbulence. The Stormscope was lighting up like a Christmas tree, showing convective action ahead.

Light turbulence soon became moderate turbulence and was increasing the longer the aircraft remained on the assigned heading. Reducing to turbulence penetration speed, we reported the turbulence and asked for a right turn, but ATC did not acknowledge the call because of constant radio communications.

Holding the airplane’s altitude was impossible, and the only thing to do was try to keep the wings and nose level.Suddenly, we flew directly into an apparent full-blown thunderstorm. It was like walking into a concrete wall in total darkness. We entered severe turbulence with heavy rain pelting the airplane. We activated our anti-ice system as well as our auto-ignition as required by procedures. Holding the airplane’s altitude was impossible, and the only thing to do was try to keep the wings and nose level. The airplane wanted to roll uncontrollably left, then right. The recovery from an unusual attitude by instruments at night in severe turbulence would be a challenge. If the airplane were to go inverted, it would be difficult to save, given our low altitude.

The pounding wall of water and what sounded like hail was so loud, the intercom was useless. The co-pilot had to shout to talk, but I could not hear what he or the communications radio were saying. Altitude excursions could not be arrested. Losing and gaining altitude was like riding a roller coaster.

Finally, after what seemed like hours but was probably only a matter of a minute, we broke out of the cell and exited the other side as easily as we had entered. Visibility was increasing and we could now see occasional ground lights. The turbulence and rain lightened up. The co-pilot advised ATC that we had encountered a storm cell and reported our position with turbulence as being severe (momentary loss of control). Having had enough excitement for one night and a desire to inspect our aircraft, we requested vectors to the nearest airport. ATC offered a heading to Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Having the diversion airport in sight, we contacted the tower and made a straight-in approach, taxied to the FBO, and parked.

The airplane was inspected that evening as well as the next day and found to be without any damage. Later that morning, after a detailed preflight and lengthy runup, we filed another IFR flight plan and departed under better conditions. Although the mission was delayed, it was accomplished easily and safely.

Some very important lessons were learned: Just because the minimum equipment list says you can fly doesn’t mean you should. There were many negatives looking right in our faces during our decision to launch: reported thunderstorms, Friday night ATC saturation, and our airplane weather radar out of service. These items were obvious red flags, but we did not see them as potential danger—only as problems that needed our solutions. Looking back, they all added up, and this story could have ended differently.

Small, isolated storm cells often merge together to form much larger cells with greater intensity. Weather can change faster than weather agencies are able to report those changes. Last, you cannot and should not depend upon ATC to keep you out of adverse weather. Remember, their first responsibility is traffic separation.

It makes no difference if you are flying a Boeing 777 for a major carrier or building solo time in a Piper PA–28-140. The FARs are clear: The pilot in command is responsible for the safe operation of the aircraft. We had complete authority to refuse this flight and no questions would have been asked. We freely chose not to exercise that right. Like Kenny Rogers once said, you have to know when to walk away.

For many years after this incident, I would often visit with crewmembers from my old unit and on board that flight. Although we occasionally disagreed on many subjects, we always agreed on one thing: We would never do that again.

Don Burkley lives in Elgin, Texas. He has an airline transport pilot certificate and has logged 13,000 hours.