Lake shore landing

An Ercoupe pilot safely lands on Chicago's shoreline

Have you heard the one about the flux capacitor? A reporter with no background in aviation arrives on the scene of an aircraft accident and the mechanic tells her, “It must have been the flux capacitor.” Back to the Future fans, you know the moral of this story. She went on air with that.

Have you heard the one about the aircraft landing on Chicago’s Lake Shore Drive? In rush hour? After flying under a bridge? That first story bears out the wisdom of the two pilots’ decision to decline news media interviews on the second.

“Ally and I declined any media coverage on this—not for lack of them trying!,” said John Ginley, the pilot of a 1946 Ercoupe that he safely landed in the middle of downtown Chicago just days after a perfect week attending EAA AirVenture in Oshkosh. “We kept our heads low and turned away any phone calls and requests. However, after decompressing and talking it over, we would like to share our story. We want our story told in the right light, to the right audience, and to people who would learn something from our experience.”

New pilot

Ginley is a corporate pilot, graduate of The Ohio State University flight program, and OSU’s flight team coach. He’s been flying since he was 15. Ally Gilbert is a new private pilot; she got her certificate just one month before the couple flew to the big airshow. They rented the Ercoupe from the flight school near where Gilbert lives outside of Columbus. They’d both flown it often. Gilbert flew left seat the 500 miles from Medina, Ohio, to Wittman Regional Airport in Oshkosh. And, after an idyllic week camping under the Ercoupe with a group of friends, Gilbert got back into the left seat to fly home.

They left Oshkosh at 11 a.m. Friday. It’s a five-hour flight home with several stops in between to fill that little aircraft’s fuel tanks. At Schaumburg, Illinois, they stopped for lunch at a spot their pilot friends had raved about: Pilot Pete’s restaurant. Their next intended spot was La Porte, Indiana, near the Lake Michigan shoreline.

Gilbert had planned to fly left seat again, but Ginley reminded her that this was the part of the trip she’d been anticipating—flying along the Chicago shoreline at 2,000 feet msl. If she wanted photos, Chicago would be on the right side of the airplane.

So, for the first time on that trip, Ginley got to sit left seat, his arm out the side of the little Ercoupe, breezing along like flying a convertible. It was a beautiful summer day and Chicago was preening under Gilbert’s camera. She was busily snapping photos when Ginley felt and heard a change in the engine sound. He’d been cruising at 2,300 rpm, and the engine dropped to 1,500 rpm. He pushed the throttle in: once, twice, and nothing happened. He exercised it again a couple of times before saying, “Hey, Al, I think we have a problem.”

Looking up from her camera, Gilbert said Ginley was white as a ghost: “She knew I was serious,” Ginley said.

They were 25 minutes into the flight from Schaumburg and just north of Soldier Field and at the edge of Lake Michigan. Ginley knew they had fuel, and Gilbert looked at the oil pressure. “Everything is in the green,” she said, and then, “Look, Johnny, there’s a baseball field.” Ginley said he had a “moment of acceptance” and needed to find the tower frequency and make the Mayday call. “I found the frequency on the iPad—135.2 [MHz]—I’ll never forget it.”

No time

Ginley was calm as he told the tower at Chicago Midway International they’d lost power. The tower was less cool, playing catch-up and asking if Ginley could make Soldier Field, five or six miles away. “The Ercoupe just doesn’t have a great glide characteristic,” Ginley said. “We had no time; there was no chance to simply glide there.”

So, the tower said: “Can you make Lake Shore Drive?”

Lake Shore Drive is a 20-mile expressway that runs parallel with and alongside the Lake Michigan shoreline. The Ercoupe was now at 1,300 feet msl and its engine was producing only 25 percent power. “I could feel us coming down and I saw Lake Shore Drive out the corner of my eye,” Ginley said. “It was our best shot.”

“Johnny was focused, but I got emotional,” said Gilbert. “I saw a lot of cars and I thought, Someone is going to get hurt.”

She stayed quiet and Ginley asked her to squawk 7700. “She is someone who knows what she was doing. I was grateful there was another pilot next to me.”

The blue-and-yellow Ercoupe was 75 feet agl and preparing to land on a four-lane highway and in the southbound lane when Gilbert saw the unbelievable: the 35th Street pedestrian bridge.

“We were not going to be able to go over the bridge. I had to go under the bridge but over the cars on the road,” said Ginley. “It was like threading a needle. I pushed the nose down and pulled the throttle again. Turned the mags off. Turned the engine completely off.”

And ahead was a sea of brake lights.

On the scene

Gilbert saw the whole thing in slow motion. She saw the bridge appear behind the trees. She saw a biker on the bridge. She saw a police officer on the side of the road. She locked eyes with him.

And then they were landing, and the left lane seemed to clear of traffic. Ginley thinks he landed with his foot on the brake. He turned slightly to the left and the tires hit the curb. Their headsets flew off, as did his glasses. They came to a stop in 400 feet.

The propeller stopped and, in that moment, Ginley feared they’d be rear-ended by a car. He told Gilbert “we have to get out” but she was frozen, crying, and couldn’t move. He unfastened her seat belt and got her out of the aircraft. They stood for a moment, and he hugged her.

“The cavalry arrived within minutes,” Ginley said. The police officer on the side of the road had called in the emergency. “Every police car, ambulance, and firetruck, as well as news teams. It was calm and then chaos. We walked around the aircraft and there was absolutely not a scratch on it. We were amazed.”

Both knew immediately they had to call their parents—“before the news tells them.” Ginley called his father, who knew immediately something was wrong. His son assured him they were OK. Gilbert tried to call her father but was crying uncontrollably, so Ginley took the phone. “He got tears in his eyes telling my dad,” Gilbert said.

Media outlets were lined up to talk with them, but Ginley and Gilbert decided to stay out of the spotlight. The police officer who had been on the side of the road walked them behind a firetruck, and the Chicago Fire Department media affairs officer dealt with the reporters. The aircraft was towed away, and Ginley and Gilbert followed in the police car.

Lessons learned

The two young pilots had played a sort of game as they were flying to and from Oshkosh—the “where would you put down if something happens” game. As many times as they’d flown together, they’d never played it before.

“We’d flown over endless fields, and this was the one spot where it just couldn’t happen,” Gilbert said. “But it did.”

“The thing I remembered—what Bob Hoover said—fly the airplane into the crash. I saw no other option. I’ve flown the airplane a lot—120 to 130 hours. I really knew how it felt, I knew its energy,” Ginley said. “I had a very calm feeling. I knew I’d done everything I could. I have no regrets.”

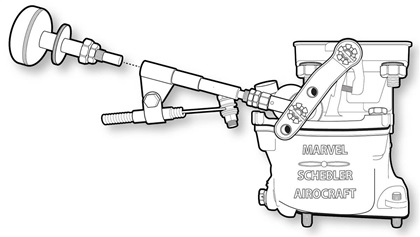

The Ercoupe was towed to Chicago Executive Airport, and the FAA investigated. The throttle cable had broken off at the carburetor and the engine had vibrated the throttle back to idle, so Ginley had no throttle control. “It was a freak occurrence,” he said.

Within the month the couple was flying again, and Ginley was back at work. “We knew we needed to get back on the horse,” he said. “And we knew we were fine as soon as we took off.”

Expert advice

Throttle malfunctions

What to do if it happens to you

1. Throttle cable breaks or the attachment at the carburetor becomes disconnected.

Every throttle cable wears over time with use. The wear can occur rapidly in areas where the cable is routed so that it has a bend in it. The bend causes the inner movable section to contact the outer conduit with more force than in the straight sections. This wear can go undetected since the conduit hides the inner cable. In extreme cases, the inner cable may wear thin enough to cause it to break.

Every throttle cable wears over time with use. The wear can occur rapidly in areas where the cable is routed so that it has a bend in it. The bend causes the inner movable section to contact the outer conduit with more force than in the straight sections. This wear can go undetected since the conduit hides the inner cable. In extreme cases, the inner cable may wear thin enough to cause it to break.

Some carburetor manufacturers install a throttle opening spring on the shaft of the throttle valve. The spring is wound around the shaft and applies a light, constant tension causing the throttle valve to advance to a wide-open position if the throttle control cable breaks or becomes separated from the throttle arm.

If a throttle cable in a carbureted engine with a fixed-pitch propeller breaks or separates in flight, the pilot would encounter one of two scenarios. Pilots of airplanes with carburetors without throttle opening springs—such as the Ercoupe—or with weak springs would see the throttle setting and engine rpm remain close to wherever the throttle was set when the malfunction occurred. Pilots of airplanes with carburetors that have functioning throttle opening springs would see the engine rpm rev up to a full-throttle setting.

In airplanes with controllable-pitch propellers the rpm would increase initially, then be governed down as the propeller governor attempts to maintain a constant rpm setting. The manifold pressure would increase to the maximum for the given altitude if the carburetor has a functioning throttle opening spring.

In all these cases, pushing or pulling the throttle knob would have no control over the engine power.

With a fixed-pitch propeller, a strong throttle opening spring, and the engine stuck at the maximum power setting, a pilot would most likely have to get into position over or near the runway where a safe glide to touchdown is assured, then lean the mixture until the engine begins to stumble in order to lose enough speed and altitude to be able to land.

With a controllable pitch propeller, a strong throttle opening spring, and the engine stuck at the maximum power setting, a pilot could lower the rpm somewhat by using the propeller pitch control, until the governor and propeller were at the course pitch limit. Pilots in this situation would most likely also have to lean the mixture until the engine lost some power once the airplane was within safe gliding distance to the runway.

With a weak throttle opening spring or no spring and a broken throttle cable, a pilot might still have enough available power to fly back to the airport, depending on where the throttle was set when the failure occurred. In any case, airspeed and altitude should be monitored and kept within a safe range.

2. Throttle cable housing slips in the clamps.

The movable inner section of the throttle cable is attached to the carburetor throttle arm directly with a rod end, bolt, and nut. The outer conduit is clamped to an immovable structure. If the conduit loosens and begins to slip in the clamp, the push-pull motion of the throttle knob in the cockpit will cause the entire cable to bend or flex. The pilot might be able to control some movement of the throttle valve, but would not have control over its full range of motion.

3. Engine stumbles or hesitates as throttle is advanced.

Most of the time, pilots advance the throttle in a smooth motion, but there are times when engine power is needed suddenly. Gusts of wind or a hard bounce upon landing can cause an airplane to be lifted several feet back into the air with no airspeed or momentum left to glide to the runway again. In these cases, the pilot has to advance the throttle rapidly.

Whenever the throttle is advanced rapidly, the throttle valve opens suddenly. This gives the carburetor throat and engine-intake system a sudden burst of air, but it takes a split second for the fuel flow coming out of the carburetor fuel nozzle to increase enough to match the increased airflow. The big gulp of air without the matching amount of fuel causes an overly lean mixture. This can cause the engine to stumble.

In order to prevent too lean a mixture from occurring as the throttle is advanced quickly, most carburetors are equipped with an accelerator pump. The accelerator pump is simply a plunger that is directly attached to the throttle valve shaft. Every time the throttle is opened, the accelerator pump is pushed down, forcing a stream of additional fuel out of a standpipe mounted next to the main discharge nozzle. The faster the throttle is opened, the greater the amount of fuel that is thrust out of the standpipe. As the throttle is retarded, the accelerator pump plunger is pulled up, allowing fuel to refill the plunger chamber.

The extra stream of fuel provided by the pump as the throttle is advanced matches the big gulp of air to ensure that the fuel-to-air ratio remains combustible.

Carbureted engines that stumble whenever power is added suddenly often have defective accelerator pumps. If the engine stumbles as the throttle is advanced, retarding the throttle for a second then slowly advancing it will allow the fuel flow from the main discharge nozzle to catch up.

An airplane with an engine that stumbles as the throttle is advanced should be examined and repaired by a mechanic.

4. Throttle control jammed.

Although rare, there are some cases in which the throttle control becomes frozen. Corroded throttle cables or a stuck accelerator pump plunger can seize the throttle control in place.

Some airplanes utilize vernier-style throttle cables that can be twisted for fine adjustments, or moved forward and aft by depressing a center button for large adjustments. Older versions of the vernier cables can jam in a fixed position once enough wear occurs in the internal cable mechanism.

A pilot encountering a jammed throttle in flight would be stuck with whatever throttle setting was in place when the malfunction occurred. —Jacqueline Shipe