Just for fun: Dubious honor

Aviation clubs you might not want to join

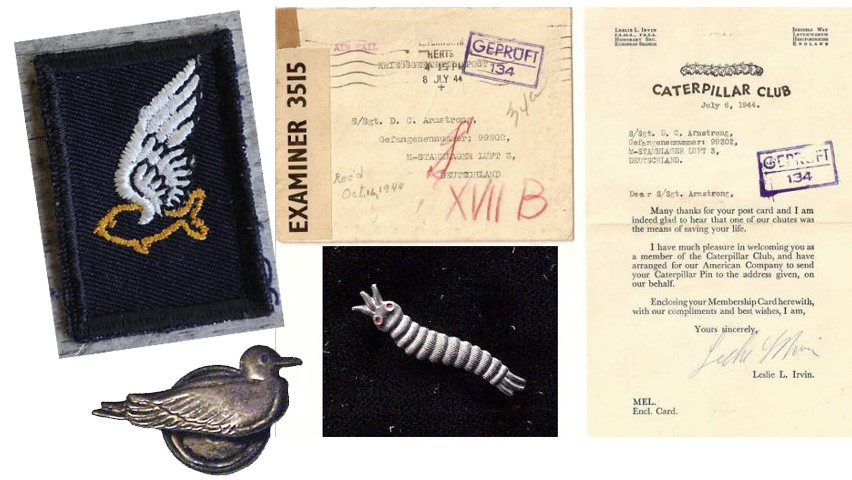

A man named P.B. Cow (some things you just can’t make up) was an inventor of all things rubber—the hot-water bottle a specialty (ask your grandmother; the bottle wasn’t really a bottle). In 1938, his protégé and eventual owner of the company that came to make the rubber for life vests and life-saving inflatable rafts called dinghies, C.A. Roberston (known as “Robbie”), was so touched by airmen who thanked the company for saving their lives when their aircraft were forced to ditch, that he created the Goldfish Club for those who had ditched in an airplane. U.S. Navy aviators wore the club’s patch on their Mae Wests (life vests named for the remarkable chest of the famous actress), and the Royal Air Force wore them under their battle dress. The patch depicted a white-winged goldfish over a sea of blue waves—gold for the value of life, fish to symbolize the sea. Robertson funded the “club” and its patches with his own money. The first “Lady Goldfish” was Gloria Pullen, who ditched in a Bleriot monoplane.

Inventor Leslie Leroy Irvin made the first premeditated free-fall parachute jump, and went on to develop his own line of parachutes. He, too, was touched when airmen thanked his company—the Irving Air Chute Co.—for saving their lives when they were forced to bail out of a disabled aircraft. The Caterpillar Club’s motto—“Life depends on a silken thread”—pays homage to the caterpillar that creates the silk used in the material for parachutes. It awards a small gold pin shaped like a caterpillar to a pilot who has bailed out and survived. The gemstone eyes of the caterpillar pin also have meaning; ruby eyes are for the survivor of a midair collision.

Walter Kidde is a name you may remember each fall when you go to buy a replacement smoke detector. He started his company in 1917 with early versions of fire extinguishers, but Kidde also made rubber life rafts used during World War II. A member of the Sea Squatters Club is a navy aviator whose aircraft crashed at sea and who survived for more than 24 hours in one of Kidde’s life rafts. Members received gold pins in the shape of a duck—the club also was referred to as the “sitting duck club.”

Similarly, the U.S. Army Air Forces had the Order of the Winged Boot for airmen who were shot down behind enemy lines and walked back to their base.

Sir James Martin and his close friend Capt. Valentine Baker started Martin’s Aircraft Works in England. When Baker was killed in an aircraft accident, Martin devoted himself to safety. He created the Martin-Baker ejection seat, and the “Ejection Tie Club” began as a way to recognize aviators who were saved by ejecting from their aircraft. The dubious honor is rewarded with a tie—a necktie. Perhaps the tie is apropos because if a pilot looks down when the seat ejects, it could break his neck; the ejection can exert 12-20 Gs on the pilot as it takes off.

Last, but not least, is the Lucky Bastard Club, an honor that truly emulates the joy of living and wartime fortitude of young men and women who fight for their country. The B–17 Flying Fortress and the B–24 Liberator were the means for U.S. forces to bomb Nazi Germany. More than 115,382 crewmembers were killed during World War II on missions involving these aircraft, and the missions were tests of strength and endurance. Bone-chilling cold and long overseas missions in noisy, vibrating aircraft tested the mettle of the pilots and airmen, many of whom were barely past their seventeenth birthday. Pilots who survived more than 25 missions were inducted in the Lucky Bastard Club: “Who on this date achieved the remarkable record of having sallied forth, and returned no fewer than 25 times bearing tons and tons of [high explosive] goodwill to the Feuhrer (sic) and would-be feuhrers thru the courtesy of the Eighth Air Force who sponsors these programs in the interest of Government of the people, by the people, for the people.”

Email [email protected]

Inventor Leslie Leroy Irvin patented his own static-line parachute in 1918.

Inventor Leslie Leroy Irvin patented his own static-line parachute in 1918.