Never Again: Dancing with the devil

Ice over the Appalachian Mountains

By Joe Brinck

October 8, 1987. I was a 31-year-old mechanical engineer and CEO of my own industrial equipment manufacturing company with 571 total hours and 110 in my Cessna 210. I had flown from my base at Cincinnati West Airport in Harrison, Ohio, to Martin State Airport just east of Baltimore, Maryland, to start up a process heater at McCormick & Co.’s research and development center. Three days later, start-up complete and customer happy, I was anxious to return home to my wife and three children.

The morning dawned clear; the weather report was for a smooth ride but with cloud cover beginning west of Baltimore extending to mid-Ohio, with the possibility of ice. As was the practice in pre-internet days, my weather briefing was by phone with the requisite struggle, usually only partially successfully, to piece together a picture of the enroute weather. I filed an IFR flight plan for 10,000 feet.

N4930U was a 1965 Cessna 210E. I loved the throaty roar of her IO-520 engine. After a decade of fixed-gear flying, the act of raising and lowering the landing gear made it seem that I was finally flying a real airplane. By today’s standards, the airplane was poorly outfitted: no autopilot, no deice save the pitot tube heater, two BendixKing KX-155 nav/coms, a vacuum horizon and directional gyro, and not much else. But like all 210s, the airplane was a rock-solid IFR platform, with good speed, long legs, and huge hauling capacity, and I loved her.

As I climbed out from Martin State into what was now a partly cloudy sky, ATC vectors soon brought me west of Baltimore/Washington International and a clearance to the cruising altitude of 10,000 feet. Farther west the cloud cover gathered until it was solid IFR. Then a problem: light ice buildup on the windshield and on the wing struts. Being inexperienced with ice, I decided it was really of no concern and happily cruised along concentrating on flying the Victor airways and holding altitude. What a great job I was doing, especially on holding altitude—it didn’t vary by 20 feet. In fact, it didn’t vary at all.

Immersed in self-congratulations, I hadn’t noticed the thick ice buildup on the windshield and struts. Immersed in self-congratulations on my excellent flying skills, I hadn’t noticed the thick ice buildup on the windshield and struts. Reality hit when airspeed began to decay and the engine began to vibrate. The ice-coated propeller was visible through a small clear spot above the defroster vent on the windshield; cycling the prop didn’t help. The engine vibration became so violent I was forced to throttle back for fear of shaking the engine loose from the airframe; this lessened the vibration but increased the angle of attack. As airspeed decayed, thoughts of stalling a heavily laden, now slow and underpowered airplane in IMC suddenly sprang to mind. I made many radio calls to ATC but to no avail. I was alone in a very bad situation over the Appalachian Mountains.

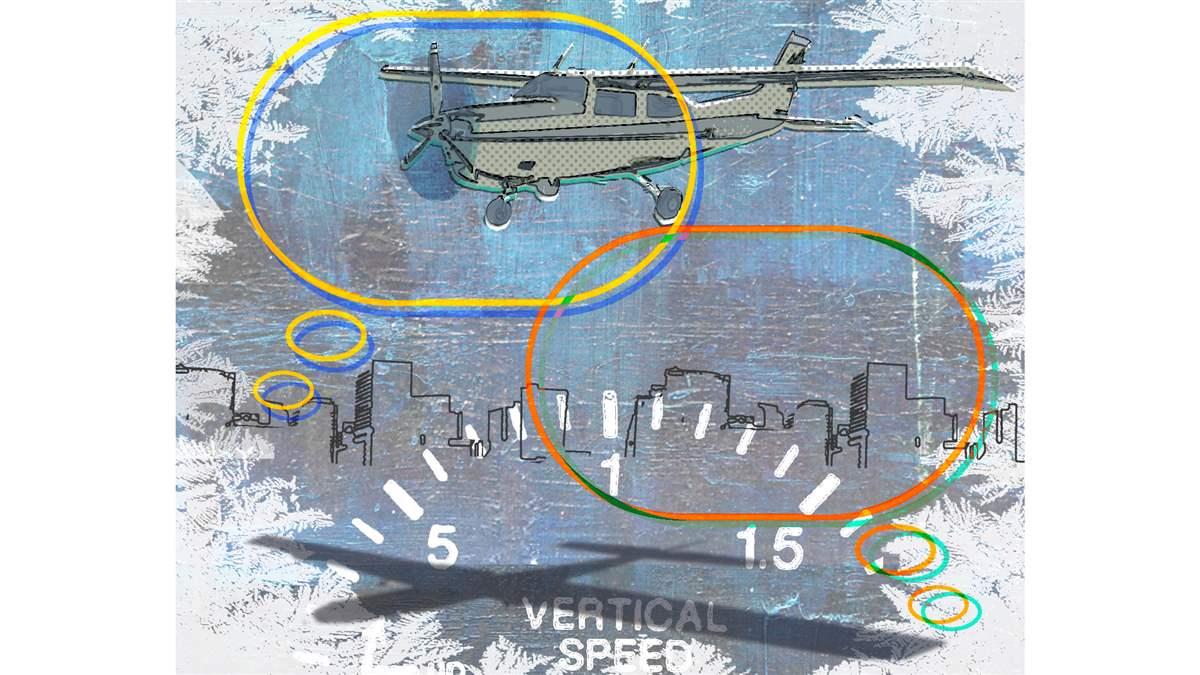

As the airplane slowed and the controls got mushier, it became clear that the altimeter might be lying; it hadn’t budged from 10,000 feet. The airspeed indicator was stock still at the bottom of the green arc. Since the pitot heat worked at preflight, the static ports must be iced, but there was no alternate static source installed.

Fortunately, in my haste to depart, I had not stowed the throttle lock but had simply laid it on the co-pilot’s seat. I carefully smashed the glass cover on the vertical speed indicator. Immediately the altimeter began to unwind fast—very fast, like the old cartoons of crashing airplanes. It stopped spinning at 3,800 feet.

A few more desperate calls to ATC went unanswered. Climbing was impossible; just holding altitude at that low power setting was a challenge. It was then that I heard a voice, not over the radio but rather inside my head. The voice clearly said, You’re going to die, go ahead and panic.

I angrily shouted “No!” and a moment later I heard a second voice: Fly the airplane, you’ll be all right. Staying on the gauges and increasing power slightly produced a bone-rattling vibration and a slow climb, about 100 feet per minute.

After what seemed an eternity of teetering at the edge of a stall while slowly climbing, I broke out between layers at 6,000 feet over Parkersburg, West Virginia. Sublimation soon began, and as the ice cleared the prop vibration ebbed enough to begin easing in the throttle, eventually to high cruise. The airspeed increased, the windshield and struts cleared up, and soon I was sailing along between layers at 165 knots.

I had neglected to reset the transponder to 7600, indicating radio failure, but after the longest hour of my life and without radio contact ATC had not missed me; at least, no one seemed surprised when I checked in 100 miles west of my last contact and at 6,000 feet instead of 10,000.

The weather at home was partly cloudy with unlimited visibility and high ceilings, the visual approach was selected and when the wheels squeaked onto Runway 36 at Cincinnati West Airport, I heaved a sigh of relief and offered a prayer of thanksgiving. Before the next flight the VSI glass was replaced and an alternate static source installed. As for the two voices I heard in my head, I prefer to think it was my guardian angel who told me to fly the airplane and everything would be OK. The other voice, I suspect, came from a realm other than heaven.

Joe Brinck is an instrument-rated private pilot based in Cincinnati, Ohio.