Space Replicas "R" Us

Craftsmen at the Cosmosphere not only restore but build from scratch

Chances are good that space craftsmen living in Hutchinson, Kansas, have touched all our lives. They work in a space junkyard called SpaceWorks—with a mean junkyard dog next door—part of the Cosmosphere, a museum a mile away that matches the quality of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. When Soviet war planners looking at spy satellite photos spotted rockets outside the modest complex in the 1980s, they assigned a nuclear missile to it, thinking it was a rocket factory. It was, and is, but the rockets either flew long ago or are replicas of the real thing.

You have seen the work of these five craftsmen if you saw Apollo 13, Armageddon (astronauts destroying an Earth-killing asteroid), Space Cowboys (astronauts destroying a Russian satellite full of nuclear-tipped missiles aimed at the United States), or From the Earth to the Moon (a Tom Hanks series on HBO about the Apollo missions).

Apollo 13, based on the true story of the NASA mission, was the most demanding project. “The Apollo 13 movie prop had to be perfect, dead-on,” recalled SpaceWorks craftsman Sean Crow.

“I believe up to 80 percent of all the props and hardware [for the movie] were fabricated here in Hutchinson by our technicians,” said Jim Remar, president and chief executive officer of Cosmosphere.

“We produced high-fidelity command module and lunar module interiors, all the in-flight garments, and spacesuits,” he said. Everything provided was a replica of the real thing, down to tiny details. While many museums restore and preserve, Remar said Cosmosphere’s SpaceWorks is the only one that adds replication to the list.

Where does SpaceWorks find the talent to reverse-engineer some of the most complex machinery in history? Right there in Hutchison, a town struggling to come back from a bruising battle with the economy that left vacant stores both downtown and at recently built malls.

Jim Harris can scratch-build an airplane, or just about anything, and make it fly.“There are five people plus outsource vendors—Central Welding and Machine is just down the street—plus a model maker in Seattle and a contractor near Orlando, Florida,” Remar said. SpaceWorks adds $1 million in revenue a year to the Cosmosphere budget.

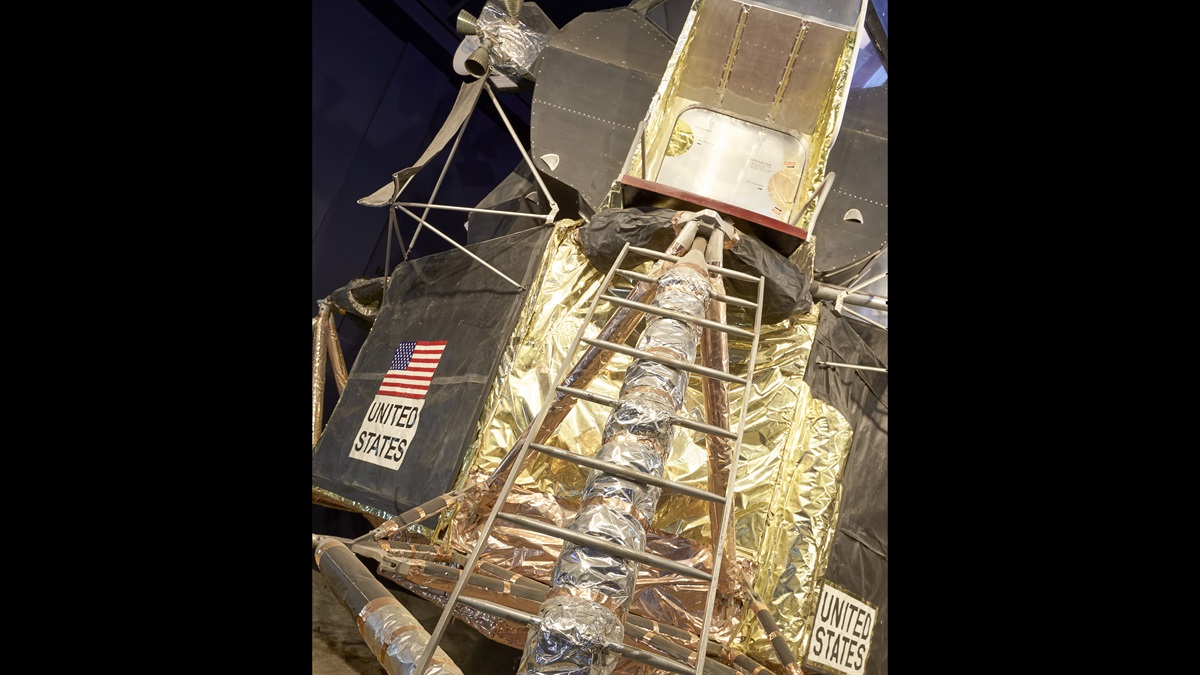

When AOPA Pilot visited in 2016, SpaceWorks craftsmen were building an exact replica of the Apollo Command Module, the cone-shape vehicle in which astronauts conducted trips to the Moon’s surface. As you read this, the module is in Rome touring as part of a larger traveling exhibit called Cosmos Discovery.

Remar said the exhibit is being produced and promoted by a company out of Prague called JVS Group PL (Just View the Show). “It tells the story of the past, present, and future of space exploration,” he said. “We’ve been able to provide more than 200 artifacts to the exhibit. We are doing six major replicas; we just shipped a full-scale lunar rover as well as a full-scale Mercury spacecraft. We did a full-scale reproduction of the chimp couch that Enos [the chimp] flew on [September 13, 1961], as well as a full-scale reproduction of the Spirit and Opportunity Mars exploration rovers.”

Enos completed one orbit in a dress rehearsal for the flight of John Glenn, but the capsule overheated and an experiment meant to shock Enos only when he did the wrong thing shocked him instead 76 times when he did the right thing. The final two orbits were aborted, and Enos was returned angry—but alive—to Earth. John Glenn’s first manned suborbital flight took place February 20, 1962. In October 2016, SpaceWorks was to ship a full-scale reproduction of the space shuttle cockpit interior.

So who do you call when a spaceship replication order comes in? In the case of Franko, you call in a commercial artist. He spent 39 years as advertising manager for the Dillons grocery store chain based in Hutchinson. “This is basically art,” Franko said. “It’s re-creating. It’s an illusion. It’s not real but it’s supposed to look real.” He said he got all his space expertise on the job. Franko found he had to be resourceful when building a spacecraft. A magnifier sold by Walgreens pharmacy was discovered to be a perfect fit for the one used for the Command Module’s attitude indicator.

Like Franko, Don Aich is also a master of just about everything. He was in the commercial glass business 20 years but also does carpentry. On the day of AOPA Pilot’s visit, he was re-creating a cabinet used in the command module. Many of the exhibits in the main museum are in glass enclosures he built.

“This is basically art. It’s re-creating. It’s an illusion. It’s not real but it’s supposed to look real.” -- Jim FrankoJim Harris, a machinist, was reverse engineering a command module camera mount. Harris has a hobby that provides needed skills at SpaceWorks: He can scratch-build an airplane or just about anything and make it fly. Such as his replica of a Toro lawn mower that flies. The body of the drone is the wing, and the handle is used to balance its weight. “It usually does something [gets damaged] every time I land. It’s very hard to fly,” he said. He has made wings from flat foam board and made them fly. Like Franko, he was a manager at Dillons.

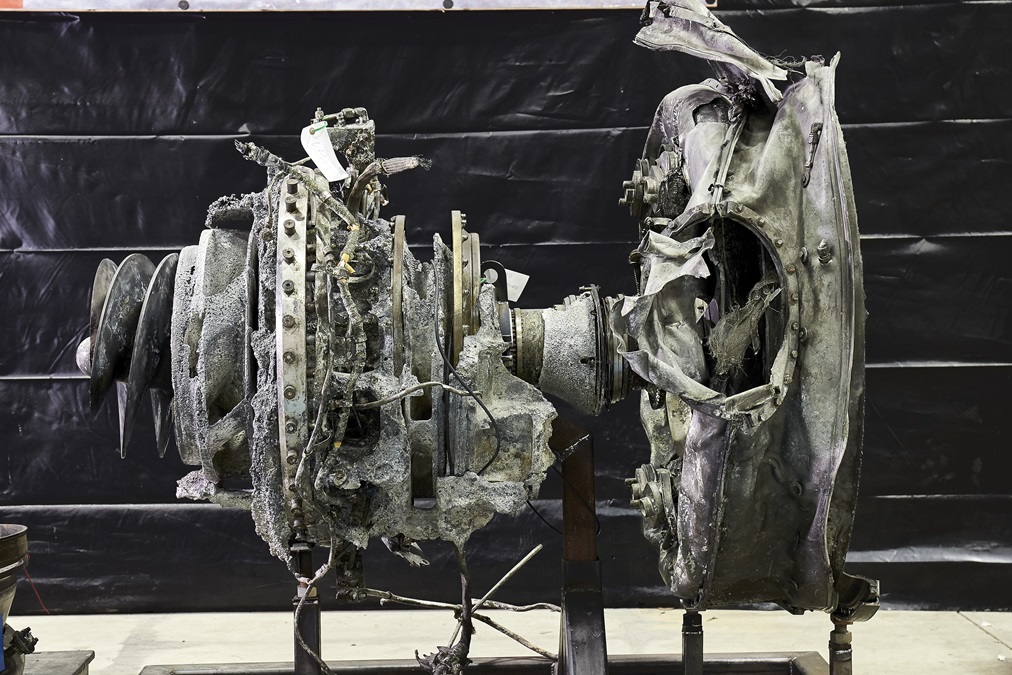

Replication is what separates Cosmosphere from other museums that do only restoration and preservation. But its craftsmen are equally at home with the real thing. One recent “real thing” was restoration of Saturn 5 first-stage rocket engines recovered from the ocean floor by Bezos Expeditions, owned by Jeff Bezos, Amazon CEO, president, and chairman (and owner of The Washington Post). Once pulled to the surface it was discovered that one of the engines had been the center engine of five that lifted Apollo 11 off the pad with the first men to walk on the moon. The lower part of the engine was destroyed after hitting the ocean following freefall from 200,000 feet, but the top portion of the engine—where 2.6 tons of fuel mixed and burned every second—survived. In 2018, it will be transported to the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum for exhibit. The other engine parts recovered from the same area of the ocean were from Apollo 12 and the ill-fated 13.

A project that gained the most notice was the restoration of NASA astronaut Gus Grissom’s Liberty Bell 7 capsule after it blew its hatch prematurely—possibly because of damage on landing—and sank in July 1961. The craftsmen recovered Mercury dimes with initials scratched on them that had been given to Grissom by the ground crew. His Model 17 Astro Randall survival knife was found as well ($535 in today’s catalog; Mercury astronaut Gordon Cooper did final design). It has a 5.5-inch blade made from quarter-inch stainless steel.

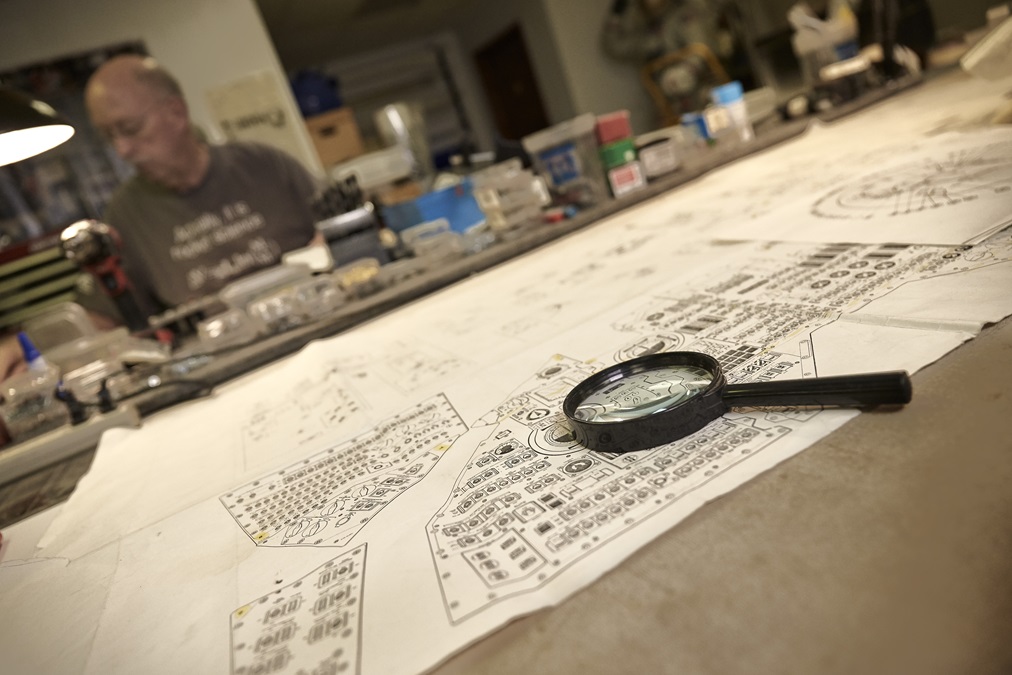

In addition to talent, the craftsmen share an additional quality: the ability to teach themselves enough about an object to re-create it. “There’s not a school that teaches you about spacecraft restoration,” Remar said. “What you can do is bring technicians who understand welding, machining, or painting—and bring those disciplines to the table and allow them to learn and study about the artifact. Fortunately, in our collection we have a lot of firsthand examples of the artifact. They study the blueprints and teach themselves about the artifact.

“Probably the most moving thing we have found [was when] we restored an original V–2 for the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton at Wright-Patterson [Air Force Base],” Remar said. “We found the word ‘crematorium’ written on one of the fuel tanks. And then what appeared to be a pencil drawing of the maps of Peenemünde,” the German municipality where the V–2 rocket was developed during World War II. “We also found embedded in the framework and the engine, two .50 caliber slugs. It appeared this particular V–2 had been strafed by Allied planes. The writing would have been done by slave laborers.” Another V–2 is on display in the Cosmosphere.

SpaceWorks built the exhibits for the Evergreen Space Museum segment of the Evergreen Aviation and Space Museum in McMinnville, Oregon. It includes a full-scale replica of a mechanized lunar rover, a full-scale lunar module, an Apollo command module and a full-scale Gemini two-astronaut capsule.

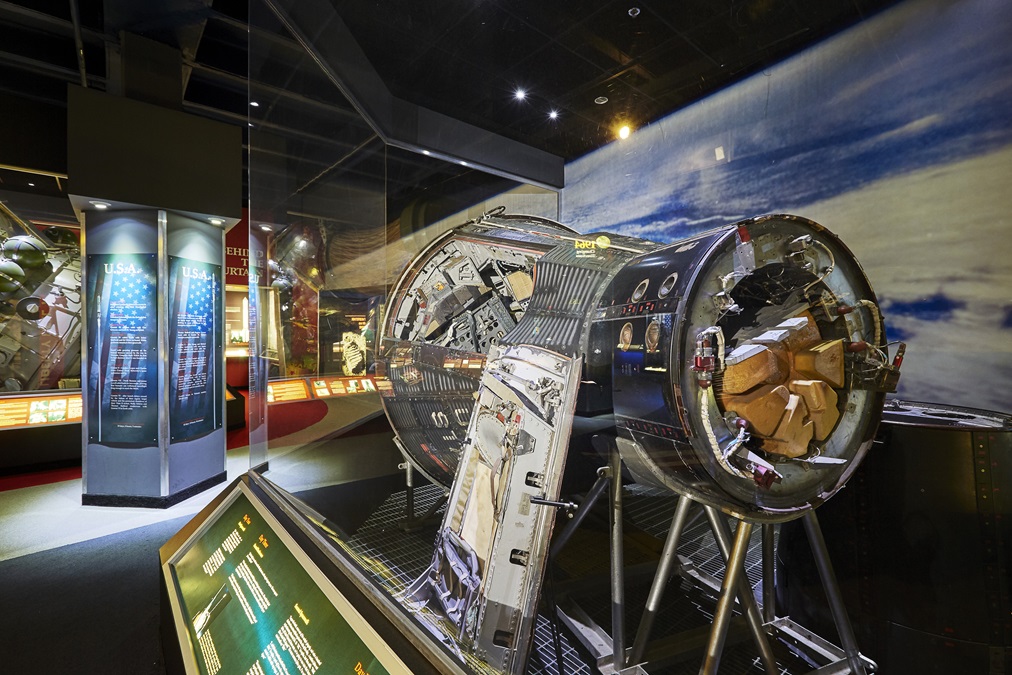

The Apollo 13 Command Module Odyssey is also on display at Cosmosphere in Hutchinson. NASA gutted it in the process of finding out what went wrong when the service module attatched to it exploded; it was then sent to the science center (Cité des Sciences et de l’Industrie) in Paris. Eventually it came back to the United States where, for more than 20 years, the Cosmosphere acquired original components and installed them back into Apollo 13. The Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum has placed it on loan to the Cosmosphere, where it remains today.

The only two permanent staff craftsmen are Dale Capps, who manages the operation, and Aich. Others are temporary or contract workers. Fabricator Larry Goodwin has already left for Denver. Franko, who has retired twice from SpaceWorks and once from Dillons, says he won’t be back. Sean Crow was a contract worker and has left. Where will the next restorers of spacecraft come from?

Capps—at SpaceWorks 18 years—always seems to find the right people, right there in Hutchinson. “My guys are getting old enough that they want to retire for real,” he said. The skills are anything but common. “I never thought I would be anodizing space suit connectors,” the former diesel engine mechanic said. He turns to craftsmen with basic skills, like welding, who are willing to work hard, but have one important ingredient: imagination.