Never Again: Heading which way?

Normal instrument approach turned emergency

By Austin Kallemeyn

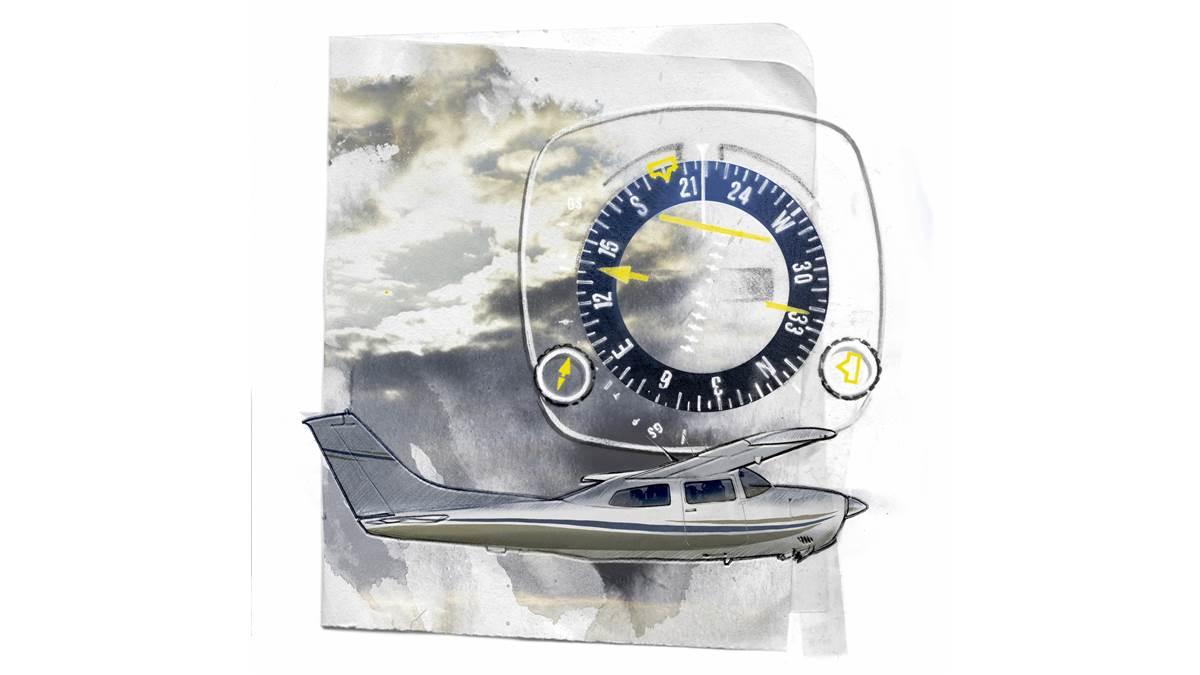

“Centurion Three-Six-November, are you receiving the localizer?” was the first radio call I heard from Minneapolis Approach after becoming established in our left turn to a heading of 200 degrees. This turn was supposed to put us on an intercept angle for the ILS approach. Luckily, I knew what was wrong. During our turn to heading 200, our horizontal situation indicator got stuck on the heading of 220.

In December, I had flown from northwest Iowa to central Iowa to pick up two more passengers, up to Minneapolis, and then back. I had flown these passengers to many home Minnesota Vikings games. The weather across most of the route was IFR, but I could not have wished for a more capable aircraft in which to tackle the weather. The flights were conducted in a Cessna 210T with three altimeters, a Garmin digital attitude indicator, backup attitude indicator, Garmin GNS 430W GPS, and much more. Additionally, this 210 has a TKS ice protection system. The airplane’s pitot-static inspection had been completed in the past month.

The first flight of the day went as planned. We departed immediately into instrument conditions, but the weather improved as we approached our first stop in central Iowa. We picked up our passengers and departed for Minneapolis. As we got closer to the Minneapolis Class B airspace, air traffic control stepped us down in altitude and told us to expect the ILS approach for Runway 14 at St. Paul Downtown Holman Field. As we approached from the south, the controller gave us a series of headings to the northeast along with the altitude changes. We were on autopilot during this time, dialing in headings via the HSI.

To the northeast of the airport, ATC cleared us for the approach. They assigned us heading 200 and 3,400 feet to intercept the localizer for the ILS 14 approach.

When the HSI stuck on 220, I immediately disconnected the autopilot. I looked at the bouncing magnetic compass but found no help. As we were near the top of the overcast layer, I saw blue sky but not a clear horizon. The next step was to look at the georeferenced approach plate on ForeFlight as a situational awareness tool, to assure myself I was not heading toward any obstacles.

That’s when the air traffic controller noticed something was amiss. I had followed each assigned heading, but the last one proved difficult. ATC issued a new heading. No reply. I was quickly overwhelmed by maintaining control and flying in a safe direction. Aviate, navigate, and then communicate. ATC asked if we were picking up the localizer. Soon after, I had the time to tell the controller our directional gyro had failed and we would have to execute the missed approach.

Suddenly, the controller was asking me if I was declaring an emergency. A couple things ran through my mind. If I declare an emergency, I will be king of the sky until I am down safely; I will have all the help I need; and I’m much more immune to receiving a pilot deviation for not following a clearance. Along with those positives, I have also watched plenty of AOPA Air Safety Institute case studies in which pilots get into trouble much worse than this and hesitate to declare an emergency. Many of those pilots don’t make it. I told the controller, “We will go ahead and declare an emergency.”

Once the emergency was declared, the controller said he would be issuing no-gyro turn instructions. This involves the controller telling a pilot in real time when to start and stop standard rate turns, and in which direction. The controller proceeded with protocol, asking for souls on board and fuel remaining. I maintained 3,400 feet while doing the turns the controller issued. We got back on an angle to intercept the ILS, and as the needle started to center, I turned inbound. The controller said we were doing great and transferred us over to the St. Paul control tower. Meanwhile, I had instructed two passengers who had many flights in general aviation aircraft to look ahead for a runway, while I was focused on maintaining the localizer and glideslope. After breaking out at 600 feet above ground level, an uneventful landing ended the emergency.

I learned a few things from this experience. First, instrument failures are not like training when your instructor covers the instruments and deems them “failed.” They are very unexpected. Keep sharp on partial-panel instrument flying.

Second, have situational awareness and use all available resources. ATC was a valuable resource, but I also had georeferenced approach plates, GPS direction track, and experienced passengers to look for a runway while on the approach.

Last, don’t be afraid to declare an emergency. It’s better to have any and all assistance available than to regret it later. The time between declaring the emergency and landing was about 15 minutes. Any extra time spent in the air is time for something to go wrong. The only action the FAA took following the incident was to give me a call the next day to gather details. The flight standards district office inspector reiterated that most pilots don’t declare an emergency when they should.

Thank you to all the air traffic controllers who helped us out of a stressful situation on that day.

One of the biggest contributing factors to a positive outcome is the lessons learned from other pilots’ stories. I highly recommend reading NTSB reports and watching AOPA Air Safety Institute videos. To continue improving accident/incident statistics within aviation, our learning needs to continue long after the checkride ends.

Austin Kallemeyn is a flight instructor for Iowa Lakes Community College in Estherville, Iowa.