Technique: I follow roads

Still a sound strategy in the age of GPS

In July 2017, Jim O’Donnell, a pilot from Long Island, New York, demonstrated that it’s possible to land on a highway in one of the busiest suburbs in the nation. After departing Brookhaven Airport, O’Donnell’s Cessna 206 developed an engine problem that forced him to land on Sunrise Highway in North Bellport. He touched down among the cars, rolling out under an overpass and pulling off the road onto the shoulder. The Suffolk County Police chief told ABC News, “He came in over the street sign that stretches across Sunrise Highway and was able to land in between that and the overpass. He kind of threaded the needle there, and it looks like he did a pretty nice job under the circumstances. He didn’t hit any cars, and no one got hurt.”

It’s usually suggested that pilots avoid roads as potential landing sites. They’re unknown quantities; lined by utility poles, trees, and fences; and may be narrow, steep, and in any condition. But, what about interstate highways? Our nationwide road system is built to standards set by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, and could provide an emergency landing surface built to known specifications.

Built to spec

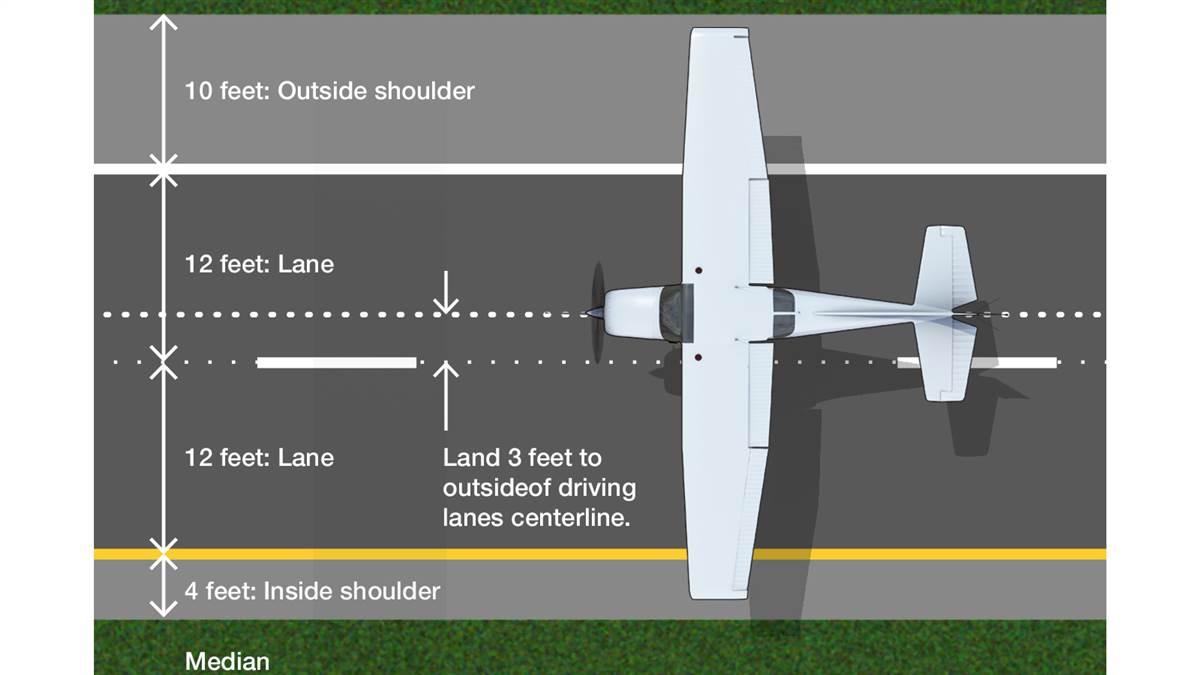

Interstate highways will have at least two lanes in each direction with a lane width of 12 feet, plus a 10-foot wide outside shoulder and a 4-foot wide inside shoulder. So, a pilot should have at least a 38-foot-wide surface for landing. In mountainous areas, it may be only 36 feet. As the number of lanes increases, so does the shoulder width requirement. While additional lanes give a pilot more space, that usually means more traffic, too.

A Piper Super Cub has a 35-foot wingspan, a Cessna 172 wing is 36 feet, and a Cirrus SR22 wing is 38 feet 4 inches. On a two-lane highway with standard shoulders you might ding the wing tip, but you should have enough room to land in one large piece. Obviously, landing precisely in the middle of the available space is essential—which isn’t always the middle of the driving lanes, as the shoulders may not be equal widths. If landing on an interstate with two 12-foot lanes plus 10- and 4-foot shoulders, you’d want to be centered 3 feet to the right of the centerline between the two driving lanes.

The maximum grade for interstates is 6 percent, or 7 percent through mountainous areas. If you can determine which way a road slopes, always land uphill. A downhill landing will take a long distance as the airplane floats while the roadway drops beneath it, and a pilot will need the brakes to stop.

Pilots may consider landing on the median, but that seems to be a worse choice than the road. It’s often filled with shrubs or trees and usually has a drainage ditch. For interstate highways, the minimum median width is 36 feet in rural areas, but it may be only 10 feet in urban or mountainous areas.

Obstructions

Power lines often don’t run parallel to interstates as they do on secondary roads. High-voltage power lines may cross the interstate, but they’re rare. Local power lines also may cross an interstate, but usually only where it crosses over another road.

Guardrails or Jersey barriers may line the shoulder of highways, too. An average metal guardrail is between 25 and 32 inches tall, easy to clear for high-wing airplanes, but a low-wing Piper Cherokee, for example, is 36 inches above the ground at the wing tip and approximately 27 inches at the landing gear. So, a Cherokee might barely clear a guardrail while landing. Some low-wing aircraft, such as the Cirrus SR22, are taller and could clear.

Concrete Jersey barriers used along many urban highways are up to 42 inches high, so low-wing aircraft should avoid these, if possible. The Cirrus SR22 wing is 42 inches above the ground about mid-aileron, so it should clear a Jersey barrier at the wing tip. The strut of a Super Cub will clear 42 inches, just 2 feet out from the wheels, so even these tall barriers are no problem for most high-wing aircraft.

The Long Island pilot demonstrated that it’s possible to roll out under a bridge, highway signs, and lights. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials standards require a vertical clearance for overhead structures of 16 feet in rural areas and 14 feet in urban areas.

A Super Cub is 6 feet 8.5 inches tall; a Cessna 172 is 8 feet 11 inches; and a Beechcraft Bonanza is 8 feet 7 inches. If your wheels are on the ground, you should clear anything built over the highway.

The clear width under a bridge will be the full paved width of the road and usually the shoulders, too. However, beneath bridges longer than 200 feet, the minimum width may be only the two 12-foot-wide lanes, plus two 4-foot-wide shoulders, for a total of 32 feet. So, a two-lane road under a long bridge, which may appear more like a tunnel, is likely to bring your airplane to a quick halt.

911

There are numerous advantages to landing on a highway—drivers will dial 911 immediately, and rescue personnel will be able to reach the site quickly. Landing in a forest, even if only a mile away from a town or highway, could mean many hours of search and rescue efforts just to locate the crash site. Also, there is enough space on a highway for a medevac helicopter to land, if needed. Those minutes could be the difference between flying aluminum wings again or earning angel wings.

Go with the flow

If you have a choice, land in the direction of traffic. You may surprise drivers by suddenly appearing overhead from behind, but that’s better than landing into oncoming traffic.

The best glide speed for many small aircraft is 60 to 75 mph, which matches much of the nation’s highway traffic speeds. Hopefully the drivers will see you merging from above and brake for your landing. If you’re over rural areas, traffic may be sparse enough to allow landing in either direction. If there’s time, consider the wind direction as well as the traffic.

Keeping miles of interstate asphalt beneath your wings when over highly congested areas or rugged terrain can add another level of safety to your flight. So, maybe more VFR pilots should consider flying “IFR.” Why not? It’s a good excuse to fly a bit farther and see more of our beautiful nation.

Dennis K. Johnson is a freelance writer and pilot living in New York City.