On Instruments: Yankees and Zulus

Same runways, same fixes, different approaches

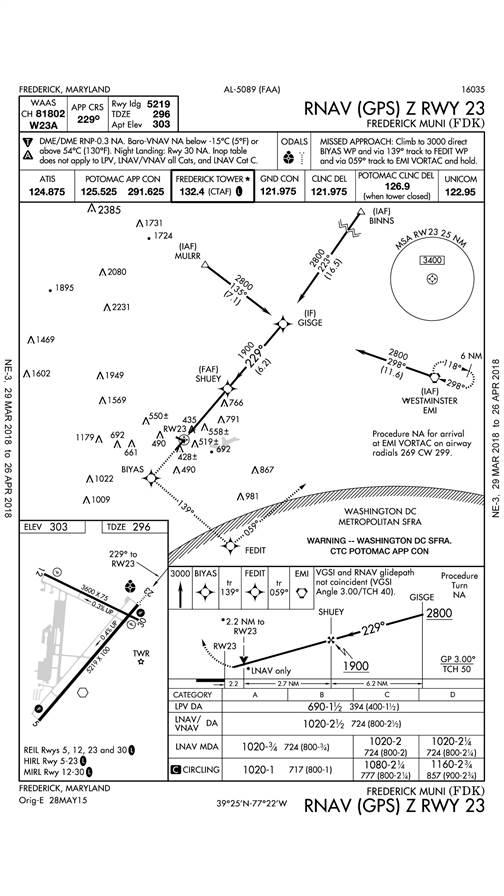

There’s an overcast at 900 feet agl, visibility is three miles in light rain, and the wind is calm. Runway 23 is active, so you’ve got several approach options.

There’s an ILS approach to Runway 23 with a decision height of 684 feet msl, the lowest of all available. But you’ve recently upgraded your instrument panel to include a WAAS GPS navigator, and you’d like to fly an RNAV approach—and this runway offers two of them.

There’s an RNAV (GPS) Y, and an RNAV (GPS) Z, but what are the practical differences between the Yankee and Zulu approaches?

You pull up the approach plates and cut to the chase. The Yankee approach lists a minimum descent altitude (MDA) of 820 feet msl. For WAAS-equipped aircraft, the Zulu goes all the way down to 690 feet msl—a full 130 feet lower—so you select it. That’s what you tell Potomac Approach, and that’s what the air traffic controller lets you know to expect.

Looking closer at the two approach procedures, however, you notice some important differences. The two approaches cross the same fixes at the same altitudes (GISGE at 2,800 feet, and SHUEY—the final approach fix—at 1,900 feet), but the Yankee approach includes one additional fix, ZITIM, a step-down fix just 1.9 miles from the runway threshold. Also, the threshold crossing heights are slightly different: 50 feet agl for the Yankee approach compared to 40 feet on the Zulu, and the descent angle on the Yankee approach is slightly steeper (3.41 degrees compared to 3.00 degrees).

The key difference between flying these two approaches with your WAAS GPS navigator, however, is that the Zulu version offers localizer performance with vertical guidance (LPV), and the Yankee doesn’t.

To pilots, LPV looks and acts just like an ILS. The needles track localizer and glideslope with increasing sensitivity all the way to the decision altitude (DA), where course width is 700 feet—just like an ILS. (Not coincidentally, the LPV and ILS minimums at this airport are virtually identical—690 feet and 684 feet, respectively.)

The Yankee approach sensitivity isn’t as accurate (0.3-mile-nautical-mile course width within 2 nm of the final approach fix). Your WAAS GPS navigator will provide vertical guidance (LNAV + V) to the MDA on the Yankee approach, but the MDA itself is unchanged at 820 feet.

Either one of the two RNAV (GPS) approaches to Runway 23 should get you below the clouds and to your destination, but the Zulu approach, with its lower DA, offers a greater margin.

If you perform a missed approach, however, expect differences there, too. First, the climb gradient for any WAAS approach is likely to be steeper—which makes sense given their lower DAs. But in this case, the missed approach flight path is altered, too.

The Yankee missed approach consists of a climbing left turn to 3,000 feet and then flying direct to the Westminster VOR (EMI).

The Zulu missed has you climbing straight ahead to 3,000 feet, then entering the Washington Special Flight Rules Area (SFRA) before going to EMI. The SFRA is well known to pilots in the Washington, D.C., area—but crossing the red line isn’t done lightly, even when flying on an IFR flight plan. Expect your GPS panel to light up with all sorts of dire warnings as you approach the SFRA, even though you’re doing the right thing by entering that highly restricted airspace. (If you’re practicing the approach in visual conditions without an active IFR flight plan, all bets are off.)

You chose the Zulu approach because of your WAAS GPS capability and lower decision altitude—but most IFR-approach-certified GPS navigators are legal on either approach. The WAAS advantage on the Zulu approach is that it gives you the accuracy of vertical guidance and a lower DA. A non-WAAS GPS could be used for the Zulu approach, but the DA goes all the way up to 1,020 feet—a 200-foot penalty compared to the Yankee approach (which contains a step-down fix the Zulu approach lacks).

Multiple approaches to the same runways using the same navaids are getting more common as the FAA adds more RNAV (GPS) approaches, so expect to see Yankees and Zulus (as well as S, T, U, V, W, and X designations) proliferate.

In general, WAAS GPS approaches will have lower DAs and steeper climbs on missed approaches. If you’ve got a WAAS navigator, you’ll be drawn to the LPV approaches for their greater accuracy and lower minimums. But make sure your airplane can comply with the higher climb gradients if you happen to miss—and that the missed approach paths don’t take you anywhere you don’t want to go.

Email [email protected]