Waypoints: Watching the magic box

Catbird seat to one of the most complicated approaches on Earth

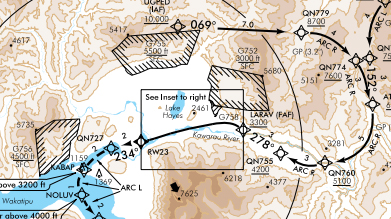

The approach, one of the most complicated in the world, looks like a question mark lying on its side—or at least it does when you start at the initial approach fix we used on the flight from Auckland. The minimum safe altitude within 15 miles is 10,000 feet; within 25 miles it is 11,400 feet. In other words, there’s a lot of brown terrain shading on the approach procedure, and the terrain depiction on the Airbus navigation display was a glimmering mass of green, brown, and yellow.

Air New Zealand Capt. Perry Earwaker and First Officer Scotty Vincent briefed the approach carefully as we dodged rain showers over the southern portion of the North Island. The pair is only one set of 20 flight crews in the whole airline who are authorized to fly the approach at night, which requires use of the head-up display. Even during the day, the approach requires special training. Earwaker explained that the approach is complicated not just by the terrain, but also by the shifting winds. Starting at 10,000 feet, the Airbus may enter the curved procedure with as much as a 120-knot tailwind while beginning a descent—go down and slow down. However, as the airplane descends into the valleys, the tailwind may disappear or become a headwind as the flight path changes directions. Further complicating are The Remarkables, a string of mountains on the edge of Queenstown that end just before the lakeshore and at about the time the Airbus swings around a corner to set up for the final segment. There, at about the time the crews click off the autopilot, the winds often shift from a headwind to perhaps a 30-knot crosswind—or maybe a tailwind. All this while trying to line up with a runway that is less than 6,300 feet long—not very long for an airliner. So you better have the speed nailed.

Although most airline operations require a stabilized straight-in approach from miles out, Queenstown has the lowest runway alignment of any Required Navigation Performance (RNP) approach in the world, according to Graham Cheal, manager of aircraft operations and airline technical support for Air New Zealand. He provided an in-depth briefing about how the approach was developed to attendees at the International Council of Aircraft Owner and Pilot Associations’ biennial World Assembly held in Queenstown in March. An Air New Zealand Airbus can be as low as 400 feet above the ground—in the clouds—before it is fully aligned with the runway, with towering terrain all around. The missed approach procedure is almost as complicated, requiring a maximum-effort climb and a curved path down the lake.

As if that isn’t sporting enough, the GPS-calculated flight path can move left or right as much as 100 meters throughout the day, depending on atmospheric conditions.

The current version of this RNP approach, first used in 2016, was years in development and provides minimums hundreds of feet lower than earlier RNAV approaches. The airline brought in a human factors expert to develop training procedures for the approach and to help pilots transition from flight director guidance to visual guidance in the final seconds of the procedure. As recently as 2008, experts had concluded that night minimums as low as those flown today were simply too dangerous.

Fortunately on the day of my flight, skies were clear and I got to see the magic box do its thing without a cloud in sight; and what an amazing sight it is.

Email [email protected]