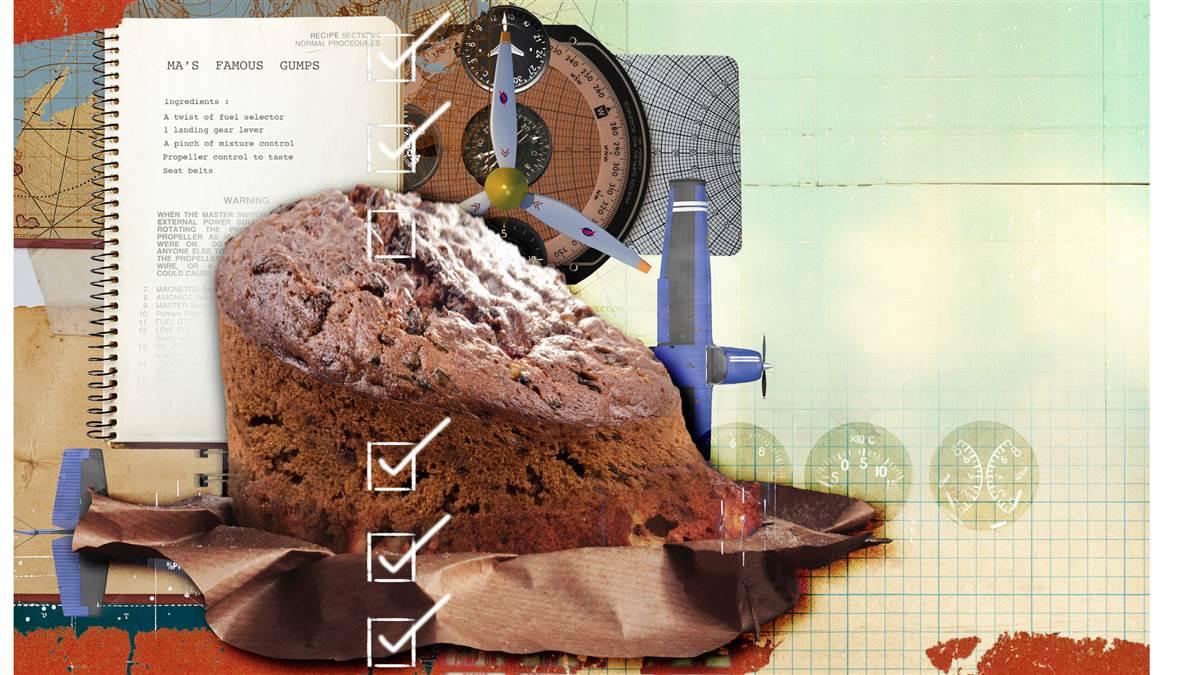

Half Baked

Follow the recipe for a perfect flight

By Charles McDougal

What if I told you there’s a proven system that guarantees you will never make a mistake? It sounds outlandish, but the simple checklist comes close.

During flight training, I remember struggling with hard-to-read laminated pages held together with O-rings, never seeming to find the scuffed page I was looking for. The checklist and its use was my least favorite part of learning to fly. But checklists provide a backup to pilots’ fallible memory. Correct and effective checklist usage in single-pilot operations can virtually guarantee an absence of critical oversights. In single-pilot operations, we use the list three ways: the Do List, the Review List, and the Checklist.

The do list

Let’s leave the challenge and response paradigm to multicrew flight decks, where it belongs. While flying single pilot, it’s a checklist, a review-before-we-do list, or a read-then-do list. On the ground and in certain in-flight emergency or abnormal situations, we use the checklist as a do list. It’s like baking a cake using a recipe: After baking a few cakes from the recipe, we know the basic idea, but we still want to look at the cookbook to make sure we don’t use the wrong number of eggs, or swap the amounts of sugar and flour. The before-takeoff checklist for a Piper Seneca specifies 33 different action items. Once we have done them a few times we pretty much know the flow of things, but we still use the checklist to make sure we don’t forget to check the throttle quadrant friction, for example—a simple item that can cause big problems if not correct.

Read the item on the list, then do or verify. Sometimes pilots find it easier to take a section at a time, as with the engine and propeller checks. Basically, though, this is a “read, then do” process. It is the most efficient and accurate method to ensure that all items are accomplished correctly prior to crossing the hold-short line.

The review list

There are certain phases of flight with high pilot workload where the checklist does not work as a “do list” or a “checklist.” I call this the “review list.” These items are typically the takeoff and landing items.

For example:

Electric fuel boost pump – On

Power – Full throttle and 2,700 rpm

Aircraft attitude – Lift nosewheel at 63 KIAS

Climb speed – 71 KIAS

Landing gear – Retract in climb before attaining airspeed of 107 KIAS

Flaps – Retract in climb

Electric fuel boost pump – Off, check pressure

The appropriate method for use of the checklist at this phase of flight is to review the items before they are accomplished so that they are held in short-term memory: “OK, let’s see, normal takeoff; I’m going to have mixture rich, throttle full, flaps zero, rotate at 55, climb at 70 to 80, and here we go.”

The checklist

Once airborne, the role of the checklist changes from “read, then do,” to “do, then check.” The pilot should know the basic pilot actions required for each phase of flight and be able to accomplish them without looking at the checklist, using it only to verify. If not, he or she should spend more time studying the airplane, the systems, the cockpit, and the procedures for the aircraft.

When it comes time to descend and approach the airport for landing, for example, the pilot should be able to accomplish the required items from memory, then pick up the checklist and move it into the field of view (no head-down reading) and confirm every item has been done. Read the item on the list, visually confirm the item is accomplished, and move to the next item. This may sound involved, but it is easy once you understand you should not be reading the item, then doing it. Know how to fly the airplane, do the items from memory, and then check their completion by reading the checklist. If any items have been forgotten or are habitually overlooked, this is where they will be caught.

Example from a Mooney M20J:

BEFORE LANDING

Seats, seatbelts, and shoulder harness – ADJUST AND SECURE

Landing gear – EXTEND (Below 130 KIAS)

Mixture control – FULL RICH

Fuel selector – RIGHT OR LEFT (Fullest Tank)

Propeller control – HIGH RPM

Wing flaps – FULL DOWN (Below 115 KIAS)

Trim – ADJUST as necessary

Electric boost pump – ON

Ram air – CLOSED (Warning Light Off)

Confirm gear down indicators – FLOOR, ANNUNCIATOR, HANDLE

As I near the traffic pattern—or before the initial approach fix, if I’m flying an instrument approach—I will have confirmed my seatbelt and shoulder harness are secure. I will have managed power controls in the descent, and switched the fuel selector to the fullest tank while still at altitude. Boost pump comes on fairly late, ram air is confirmed closed as I look around at the panel. I lower the landing gear at the final approach fix or abeam the touchdown zone in a VFR traffic pattern. Flaps come down after that (in the Mooney), and propeller eventually will make its way full forward, as will the mixture control. In a VFR pattern, I will now take a few seconds on long final or on base leg to look at the items on the checklist. I will briefly look at each item to confirm it is in the desired position. I will look at all three landing gear indications, quite deliberately. I may group a few items together; “mixture, fuel selector, prop,” for example. “Trim…oops, I’m holding a lot of back-pressure; let’s get that sorted before short final. Before landing checklist complete.”

There are times when checklist items must be accomplished out of order or omitted until later. I usually choose to fly ILS approaches without flaps extended. So I have to gradually add flaps later. In this case I probably will not return to the printed list but will have briefed myself; “before landing checklist complete except flaps to go.”

The pilot should know the basic pilot actions required for each phase of flight and be able to accomplish them without looking at the checklist.One way of thinking about checklist usage is like a clock with one hand and three positions. In normal steady-state flight, the hand is at the 12 o’clock position. When we change phases of flight we accomplish the required items. This moves the hand to the 4 o’clock position, one third of the clock face representing the first part of the process. Next, we consult the checklist to ensure that all items have been accomplished; one by one or in groups of two or three, we read the list then look at the switch, gauge, or light to confirm it is in the condition stated on the checklist. Having done this, the hand on the clock has moved to the 8 o’clock position, two thirds of the way around the clock. The final step is the verbal annunciation: (phase of flight) checklist complete. This resets the hand of the clock to the 12 o’clock position, ready for the next change in phase of flight. It’s a simple yet elegant way of thinking about a task that many pilots struggle with.

Keep trying

Once we have a good checklist and a procedure for integrating the checklist in flight that works well, there is one more challenge. As pilots become more experienced and comfortable in a given airplane, the natural tendency is to stop using the checklist. It seems redundant and sometimes silly to pull attention away from the important tasks of aircraft control, communication, traffic avoidance, passenger briefing, and more, having flown a particular airplane a few hundred times. But even experienced pilots sometimes forget items, and with practice, checklist usage becomes a natural part of flight.

As years of flight accumulate in our logbooks, the regular integration of the printed checklist will keep us sharp and efficient in its use, and in the application of correct in-flight procedures. As we move up to more complex aircraft, the discipline and skill associated with diverting our attention to the printed word to confirm checklist items becomes increasingly important. And this skill becomes crucial to survival with a partial electrical failure in a turboprop; the autopilot has failed because of low buss voltage, and night IMC conditions prevail with thunderstorms in the vicinity. On this stormy night, a pilot needs the ability to hand-fly the airplane while dividing attention appropriately to utilize the abnormal procedures or emergency checklists, which could be a combination of memory items and read-then-do procedures. No pilot would want to face such a challenging situation with rusty checklist skills.

Can excellent printed or electronic checklist usage guarantee that you never join the “belly-dragger club,” or take off with a lean mixture burning up cylinders? The answer to this is most assuredly yes.

Charles McDougal is an airline transport pilot with more than 20 years of flying experience.

A Cessna 152 lunged forward and struck a parked Cessna 172 when the 500-hour private pilot started with the wrong throttle setting. “Better adherence to the checklist may have prevented this incident,” the pilot wrote.

A Cessna 152 lunged forward and struck a parked Cessna 172 when the 500-hour private pilot started with the wrong throttle setting. “Better adherence to the checklist may have prevented this incident,” the pilot wrote. “In the process of a normal landing in light wind,

“In the process of a normal landing in light wind, Another pilot took off on the pilot’s first solo flight in a newly acquired high-performance aircraft. “During the departure phase, I became distracted because the front passenger door was not properly latched, so there was loud wind noise and cold air blowing into the cockpit (the door was closed, but not completely latched). As I was trying to figure out the door issue, Potomac Approach called and reminded me to stay clear of Class Bravo and gave me the altimeter setting again. At that moment, I looked at my Aspen unit and realized that I was ascending into Class Bravo airspace at 1,500 msl.” The pilot reported that “the pretakeoff ‘doors and windows locked’ checklist item took on new meaning for me (something I previously didn’t give much thought to).”

Another pilot took off on the pilot’s first solo flight in a newly acquired high-performance aircraft. “During the departure phase, I became distracted because the front passenger door was not properly latched, so there was loud wind noise and cold air blowing into the cockpit (the door was closed, but not completely latched). As I was trying to figure out the door issue, Potomac Approach called and reminded me to stay clear of Class Bravo and gave me the altimeter setting again. At that moment, I looked at my Aspen unit and realized that I was ascending into Class Bravo airspace at 1,500 msl.” The pilot reported that “the pretakeoff ‘doors and windows locked’ checklist item took on new meaning for me (something I previously didn’t give much thought to).”